When John Prine sang of “Paradise,” an Americana concept became a real and present truth. He wrote the song for his father, who was reared in the pastoral confines of Western Kentucky coal country. But he sang it for my great-grandparents, my second and third cousins, and great aunts and uncles who live in towns that stretch from Princeton to Madisonville, just west of Paradise. In towns this small your nation-state is the county — Hopkins, Caldwell, and Muhlenberg. Their borders foster a menagerie of the unincorporated, farmers and laborers with small plots of land and ample fortitude, with capable hands and trusting hearts. For country people, the state of Kentucky is an abstract banner of college sports, horse racing, and conservative politics. The county is your life blood. And no one had sung of the county before Prine.

Prine grew up in Maywood, Illinois, a Chicago suburb, but made annual trips to Muhlenberg County with his family, where the town of Paradise once thrived. “We used to go down there as often as we could until the town got tore down by Mr. Peabody,” Prine explained to his bandmate John Burns in a 1980 television special. “Remember that song? You have to sing it 19 times a week.” It’s true that “Paradise” was quickly a fan favorite, along with much of his 1971 debut. Today, “Illegal Smile,” “Sam Stone,” “Paradise,” “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore,” and “Angel from Montgomery” are all standards in the American songbook, stories of the overlooked and downtrodden that speak to greater sociopolitical ills, problems of poverty, war, and hypocrisy that continue to plague American society.

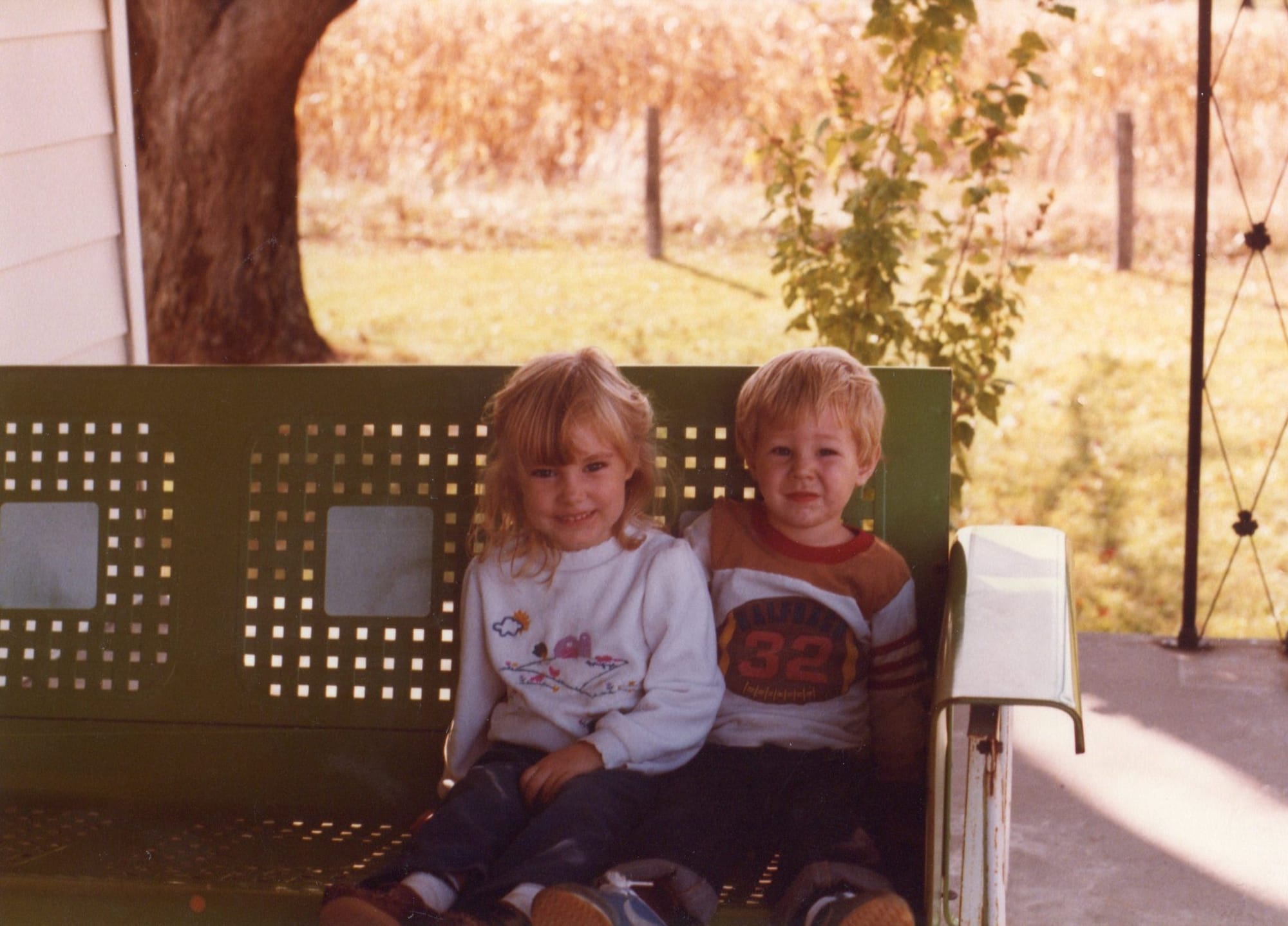

“When I was a child my family would travel / Down to Western Kentucky where my parents were born / And there’s a backwards old town that’s often remembered / So many times that my memories are worn.” This was Prine’s annual journey. But it also was my dad’s and his brothers’. They spent summers exploring muddy Kentucky creeks and frying up small game at their grandparents’ farmhouses, my great grandmother Virginia Glass cracking the insides of squirrels’ skulls into the scrambled eggs. It was also my journey, and my brother’s and sister’s, as we’d peer out the minivan window at the bulging clouds and bluegrass pastures that blurred as we sped down the Pennyrile Parkway. Before Prine, no song had ever named the place of my dad’s family specifically. After “Paradise,” a whole world became known outside of itself.

Prine is known for his profound, economical lyrics. They convey a keen sense of imagination, a childlike wonderment in everyday happenings that are universal to even city folk, peering in from their gilded high-rises. They are often weighty, but never nihilistic. Like my Kentucky family, Prine was a fan of angels, God, and Christmas. Early on, he was pegged as the “New Dylan,” but he was in fact his opposite. There wasn’t a lot of mystery with Prine. Each song reveled in the plain, brilliant imagery and characters of Middle America, the Everyman and underdog, conveying a clear and abundant place in time. In “Paradise,” it was “Where the air smelled like snakes and we’d shoot with our pistols / But empty pop bottles was all we would kill.”

Many of Prine’s words spring from modern concerns — war, women’s rights, the exploitation of laborers and the earth. There’s the tragic veteran in “Sam Stone” (“There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes”) and those seeking a simpler life in “Spanish Pipedream” (“Blow up your TV, throw away your paper / Go to the country, build you a home / Plant a little garden, eat a lot of peaches / Try and find Jesus on your own”). “That’s the Way the World Goes ’Round” underscores our nagging inclination to be our own worst enemy, finding a way to drown in a small puddle, while “You Got Gold” speaks to our inherent goodness and potential tapped by the spout of love. And then there’s the plain silly, aw-shucks side of Prine, manifested as an undies-sniffing hound dog in “In Spite of Ourselves” and a worried nail biter in “Dear Abby.” “Bewildered, bewildered / You have no complaint / You are what you are and you ain't what you ain't / So listen up buster, and listen up good / Stop wishing for bad luck and knocking on wood.” ’Nuff said.

Then, there’s the “world’s largest shovel” in “Paradise,” which emptied the soul of my family’s homeland. It’s not folklore, but a headline straight from the papers. “Then the coal company came with the world’s largest shovel / And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land.” The Peabody Coal Company’s “Big Hog” shovel indeed made Muhlenberg the nation’s top coal-producing county, uncovering 80 million tons of coal in over two decades, before it literally dug its own grave. “And daddy won't you take me back to Muhlenberg County / Down by the Green River where Paradise lay / Well, I'm sorry my son, but you're too late in asking / Mister Peabody's coal train has hauled it away.”

This sort of country parable is intrinsic to the vernacular of Western Kentucky, a simple, rhythmic form of storytelling whose anti-frivolity chain-stitches brilliant forms. It recalls my own family’s tales of my great-grandfather Melber Moore, a coal miner who survived two explosions deep underground, whose life was of a Coen Brothers film. The second blast landed him in a full-body cast and ended his mining career. When they sawed him out, a hip injury rendered one of his legs shorter than the other. For the rest of his life he wore one shoe with a lifted heel, walking door-to-door selling Watkins Company spices and extracts. I can imagine him humming Prine’s 1991 edict “Everything Is Cool,” had he been alive to hear it. “I was walking down the road man / Just looking at my shoes / When God sent me an angel / Just to chase away my blues.”

The natural gas found on Etoil and Melber’s land in Hopkins County appeared to be that saving grace, except that Melber had a fatal heart attack one day while watching the men lay the gas line. Witnessing his parents’ struggle, my grandpa Bobby Cole decided that he wouldn’t follow his father’s footsteps into the mines. He instead traveled north across the Ohio River to Evansville, Indiana, where he became a tool and die maker. My dad, today a broadcast journalist in Evansville, often wonders if he’d have ended up in the mines had his dad not made that decision.

Prine of course has a line for this, from his 1980 album Pink Cadillac. In the song “How Lucky,” he recalls walking down the streets of Maywood, Illinois. “Today I walked down the street I used to wander / Yeah, shook my head and made myself a bet / There were all these things that I don't think I remember / Hey, how lucky can one man get.” Shielded from the hardships of Hopkins County, my dad had only good memories.

We were the city folk — the Methodists — who’d drive to White Plains, Kentucky, each Thanksgiving, and Claxton, Kentucky, each Christmas, for annual reunions with the Moores and the Glasses. I was the only person I knew who had a living relationship with great aunts and second cousins, their velveteen drawl more pronounced the farther east we traveled. Cousin Barry worked the railroad. So did Uncle Wayne, before he became a preacher. His sister, Aunt Margaret, babysat kids after school. So did Wanda Sue, my grandmother.

These farmers and coal miners and health care workers were an important presence in my 20 years in Southern Indiana. Even when I’d gone north to Bloomington, Indiana, for college, and farther to Chicago for work, I’d never miss a reunion or holiday among their God-fearing ranks. I’d often make the drive to Prine’s 1971 self-titled album, listening to “Paradise” as I traced the Prine family’s tracks from the north of Illinois to the heart of Western Kentucky.

Though some in my family never listened to secular music, I was always comforted by the idea that John Prine shared their lives with the rest of the country — even the parts of their Southern Baptist identity I found the most absurd. He summed those up best in “Whistle and Fish” singing, “Father forgive us for what we must do / You forgive us and we'll forgive you / We'll forgive each other 'til we both turn blue / And we'll whistle and go fishing in the heavens.”

Upon learning of Prine’s death from complications related to COVID-19, I immediately contacted my dad. Prine was the first music he and I could agree on when I was a moody punk rock kid in the ’90s and he was an Eagles-loving hometown guy. Prine not only celebrated our provenance, he also revealed a sensitivity in my dad I’d never recognized before. His self-titled album was often too dark for my mother (“Slit my wrists,” she’d say), but for us he was the pinnacle of the kind of writer we’d someday like to be, spare and brilliant. Dad mentioned a story he’d once heard Prine tell about the first time he played “Paradise” for his father. Prine brought the tape of his first record home, before it was released, and placed it on a reel-to-reel player. His dad walked into the next room and sat in the dark as it played, because he wanted to pretend it was on the jukebox. I take comfort that in Prine’s physical absence, we can still listen in from the next room, imagining his voice from a jukebox, a concert, or in the heart of Western Kentucky.

Comments ()