EDITOR’S NOTE: The team at No Depression is saddened to hear about the passing of music collector and Arhoolie Records label founder Chris Strachwitz at the age of 92. In his honor, we're sharing this excerpt of a story about the 60th anniversary of his label from our Winter 2021 journal, "Good News."

Arhoolie is a record collector’s dream. One collector, specifically. For decades its founder, Chris Strachwitz, chased a distinct sonic muse, tracking specific forms of American and Mexican vernacular music while building a vast network of friends — scholars, collectors, and musicians charmed by his passion and good taste. He then channeled that personal passion into a record label that championed regional blues, folk, country, and gospel artists and helped usher Cajun, Creole, zydeco, norteño, and Tejano music to wider audiences.

Before Strachwitz and Arhoolie Records, bluesmen Mance Lipscomb and Mississippi Fred McDowell, zydeco artist Clifton Chenier, and norteño and Tejano stars like Flaco Jiménez and Lydia Mendoza had rarely been heard outside of their native regions. That’s doesn’t even include the label’s work with notables like Big Mama Thorton, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Del McCoury. Today, Strachwitz and his artists and employees have won numerous Grammys in categories including Best Historical Album, Album Notes, Tejano Music Performance, and Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording. Perhaps more importantly, their work has sustained one of the most important roots music labels of the last 60 years.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKeZYSWJUzU[/embed]

Music Under Siege

“I’ve just been so lucky; I don’t know when it will stop,” Strachwitz says on a phone call from his home in El Cerrito, California, about two months after his 90th birthday. Listening to Strachwitz talk about music elicits the wide-eyed wonder of kindergarteners on a carpet at storytime — the way his voice lights up, the way he luxuriates in tiny magical details, the authenticity of his enthusiasm. But Strachwitz’s particular drive originates from a childhood where his favorite records were forbidden.

Raised in the German province of Lower Silesia, which was conquered by Poland after World War II, he came of age amid Nazi rule, in an aristocratic farming family that had supplied livestock to the King of Prussia, Frederick the Great, in the 18th century. Their assistance was so appreciated that the king named them royalty, and Strachwitz — who still speaks with a light German accent — was born a count. “That designation came with a crest that was designed for the family,” he explains. “It had wild boars on it.”

Since boyhood, Strachwitz was enamored with music, listening to anything his mother (who was American) brought back from the States, along with German favorites. “Putting a needle down on a black piece of shellac turning at 78 revolutions per minute was just a miracle to me,” he says.

The freedom he felt while listening to new and exciting sounds was soon obstructed by the regime building near his family home. Strachwitz recalls the distinct moment he became aware of the threat: One day, while listening to one of his favorite German records when still in grade school, his dad explained that he couldn’t play it anymore because the composer was Jewish and the Nazi leaders in their village would punish the family if he was caught. “I will never forget that,” Strachwitz says. “I didn’t even know what a Jew was.”

The family managed to survive the war, but as Russian troops closed in, the Strachwitzes fled their estate. “We had to leave our wonderful huge farm because we were viewed as capitalists,” he explains. They immigrated to the United States in 1947, after staying with an uncle in Germany for a couple of years while his mother contacted family stateside. A well-to-do American aunt helped fund his enrollment at the private Cate School near Santa Barbara, California, where he practiced his English and became enamored with music played on area radio stations — country acts like The Maddox Brothers and Rose, The Armstrong Twins, and Bob Wills, and Mexican mariachi and conjunto ensembles. After seeing the film New Orleans starring Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong, he became a devotee of New Orleans jazz. “As a young kid growing up and not being able to listen to my favorite record, I was flabbergasted by the amount of amazing music here,” he says. “Under Hitler almost all you ever heard was march music, endless march music.”

Personal Favorites

The nonprofit Arhoolie Foundation, which works to preserve and promote Strachwitz’s extensive collection (as well as others that complement it, including those from folklorists like Harry Oster and Bob Stone) was founded in 2009. According to executive director Adam Machado, “Chris is driven by what he loves, so he’s not going to pursue something for the wrong reasons. …There is a real honesty and a real truth to the whole thing because it’s such a massive labor of love.”

By the time he enrolled at Pomona College in 1951, Strachwitz was hooked on the blues and R&B. He regularly tuned into Hunter Hancock’s famed Harlem Matinee radio show on Los Angeles radio station KFVD. “I heard Sonny Boy Williamson and Muddy Waters, but the man who really impressed me was Lightnin’ Hopkins,” he recalls. He befriended the early blues scholar Sam Charters after transferring to University of California – Berkeley and eventually, in 1959, Charters sent a postcard that’d change the course of his life forever.

“‘I found Lightnin’ Hopkins!’” Strachwitz remembers the message reading. “After that I literally took a pilgrimage to Houston. I had to meet him.

“He was just totally making up rhymes; playing on his ferocious electric guitar with a drummer behind him, singing about how his shoulder was hurting, how the chuckholes in the road were covered with water and his car would hit them,” Strachwitz explains. “I’d never encountered anything like that. I told my friend Mack that somebody’s gotta record him in a beer joint like this.”

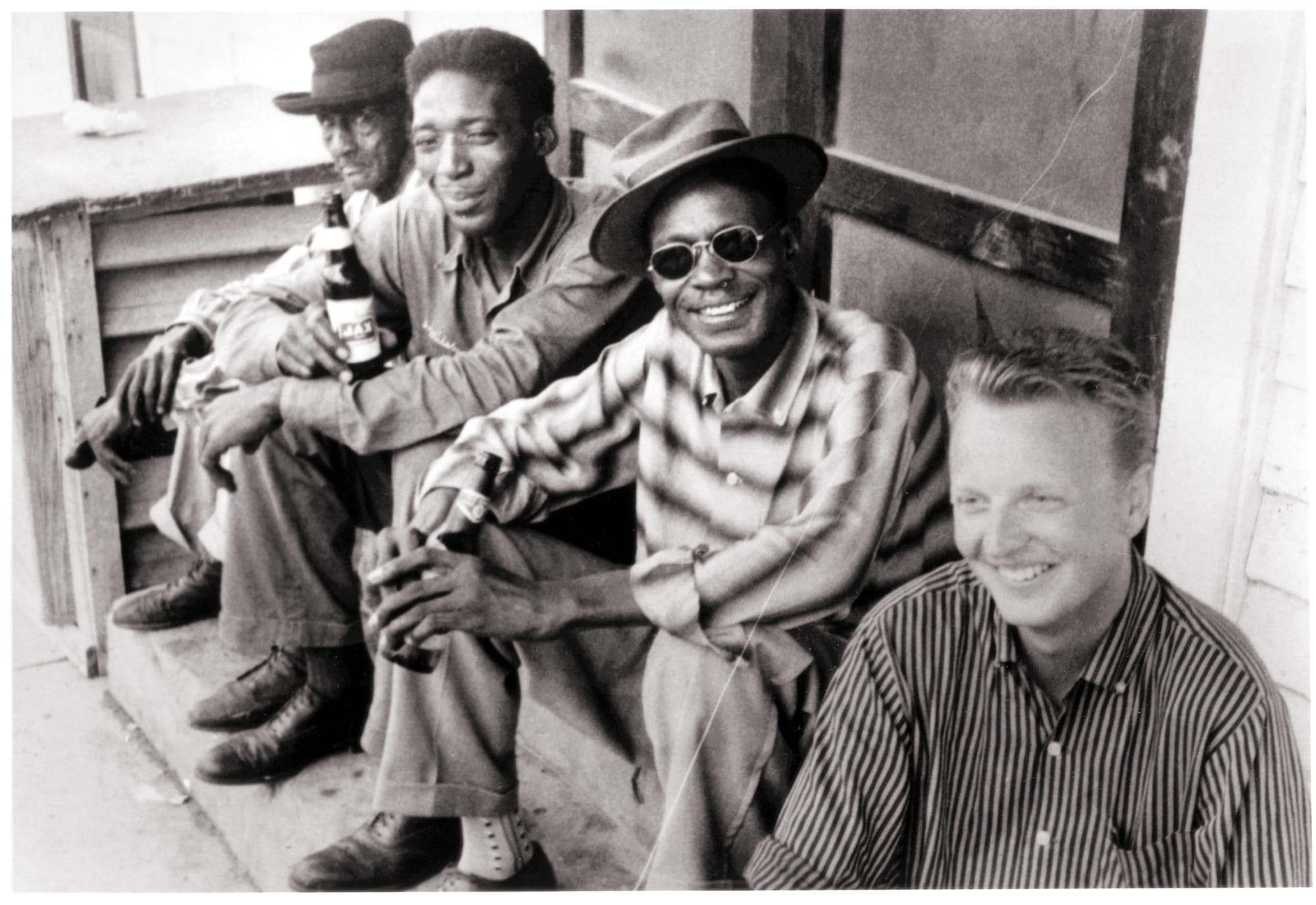

Two years later, Arhoolie Records released Lightnin’ Sam Hopkins, nine tracks that convey the raw, electrifying quality of the blues singer’s live performances, a stripped-back authenticity that listeners would come to expect from Arhoolie releases. But first, Strachwitz and Mack McCormick, a Texas-based musicologist and folklorist, stumbled upon the man who’d mark the genesis of Arhoolie Records. After tracking down the subject of the protest song “Tom Moore’s Farm,” which they’d heard Hopkins perform, the plantation owner directed the two friends to a man named Peg Leg who hung out at a train station. Peg Leg pointed them to Mance Lipscomb, who became Arhoolie’s first artist. “He gave us the address where he lived and that is how we found him,” Strachwitz recalls. "It was just an unbelievable coincidence.”

McCormick actually suggested the name for the label, a word that meant “field holler.” Though apparently, he didn’t get the word quite right, Arhoolie ended up being memorable enough to suffice. The label’s debut album, Mance Lipscomb: Texas Sharecropper and Songster, was released a few months later after that fateful meeting in 1960. Strachwitz and his friend Wayne Pope, a graphic designer, hand assembled the first 250 copies, affixing wraparound labels to black cardboard sleeves. “We had no idea what a tedious job it was,” Strachwitz explains. Pope also created the distinctive guitar-shaped logo that has appeared on every Arhoolie release and is painted on the wall of the outfit’s headquarters on San Pablo Avenue in El Cerrito, California.

From that first release, the Arhoolie Records catalog and de facto family swelled like a roomful of laughter. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Strachwitz issued albums by storied blues artists, Southern gospel choirs, mountain stringbands, hillbilly groups, Louisiana Cajun, Creole, and zydeco players, singer-songwriters, bluegrass pickers, and even a meditation record. By the 1980s and ’90s, he added numerous Tejano and norteño artists to the Arhoolie roster. Drawing on his love of Lightnin’ Hopkins’ improvised rhymes, in 1969 he released the only album by the Texas street performer George “Bongo Joe” Coleman, who is now considered a proto-rap pioneer.

Of course, Strachwitz has his own personal release highlights. In 1962, he tracked the Rev. Louis Overstreet from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to Phoenix, Arizona, in a series of fortuitous turns to record him for album simply titled With His Sons and the Congregation of St. Luke's Powerhouse Church of God in Christ. “I was just totally knocked out by the whole thing,” says Strachwitz. “Once people realize that you love their music, that you don’t mean to be a policeman or bill collector, they’re really enthusiastic and want to help,” he says.

Another favorite turned out to be one of the label’s greatest successes. Joe McDonald’s “I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag” became an unexpected hit after his band Country Joe and the Fish performed it at Woodstock in 1969, but Strachwitz had met the Berkeley-based singer-songwriter through a friend and recorded a version of the song with his modest gear years earlier. “It was a really potent song, but also kind of humorous in a way,” says Strachwitz. He became the song’s publisher and received great returns on it throughout the 1970s, which helped him purchase the building that has housed Arhoolie Records, the Arhoolie Foundation, and Strachwitz’s record store, Down Home Music.

No ‘Mouse Music’

Arhoolie Records became the sound of one man’s predilection, a vast catalog that often displays performers in their natural environments, recordings tracked with minimal equipment and auxiliary instrumentation. Strachwitz has often explained that what he loves isn’t “mouse music,” meaning that it isn’t weak. Instead, what he searches for, what really pricks up his ears, is a synthesis of strong and sweet.

In 2016, with retirement looming, Strachwitz turned over his label to Smithsonian Folkways Recordings in Washington, DC. Jeff Place, curator and senior archivist at the Smithsonian’s Ralph Rinzler Folklife Foundation, and others have since worked to catalog, digitize, research, and contextualize each of Arhoolie’s 350 releases, along with key parts of his personal collection.

“Because of Arhoolie Records, all of us have been able to experience these things we probably never would have heard of,” Place says. “No one has the complete, full-on passion of Chris Strachwitz.”

The Arhoolie Foundation marked its 25th birthday in 2020, and executive director Machado says it hopes to celebrate soon in Los Angeles, in conjunction with the University of California – Los Angeles’ Chicano Studies Research Center, which houses Strachwitz’s personal collection of commercially issued Mexican and Mexican American music — the world’s largest at more than 130,000 recordings. The Strachwitz Frontera Collection, as it’s known, is expected to be fully digitized soon. Over the last 18 years, the foundation’s head digitizing engineer, Juan Antonio Cuellar, has dropped the needle on each of the Frontera collection’s 78 rpm records and 45s, listening to them in real time to make sure the sounds transfer faithfully and to properly catalog each disc. “It’s a monumental accomplishment,” Machado says.

The foundation also received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 2020 to expand its digital presence, a key boost in a time when music distribution and performance has relied heavily on online platforms amid the pandemic. The Strachwitz Frontera Collection YouTube channel, for example, now has more than 30,000 subscribers. “A lot of the people out there whose grandfather or mother or sister or friend is on these recordings are contacting us and saying, ‘Holy smokes, I never thought I would hear this record,’” Machado says. “And then we ask them to tell us about their grandfather. These great exchanges are happening. It’s exciting."

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j3bQlWfSE0M[/embed]

Comments ()