JOURNAL EXCERPT: Bobby Osborne Returns to the Top

EDITOR’S NOTE: The team at No Depression is saddened to hear about the passing of bluegrass legend Bobby Osborne at the age of 91. Throughout his career — with his brother Sonny Osborne as well as a solo artist — the mandolinist and vocalist helped shape the entire musical genre. In Osborne’s honor, we’re sharing this feature about his last studio LP, Original, and more from our Spring 2018 journal, “Appalachia.”

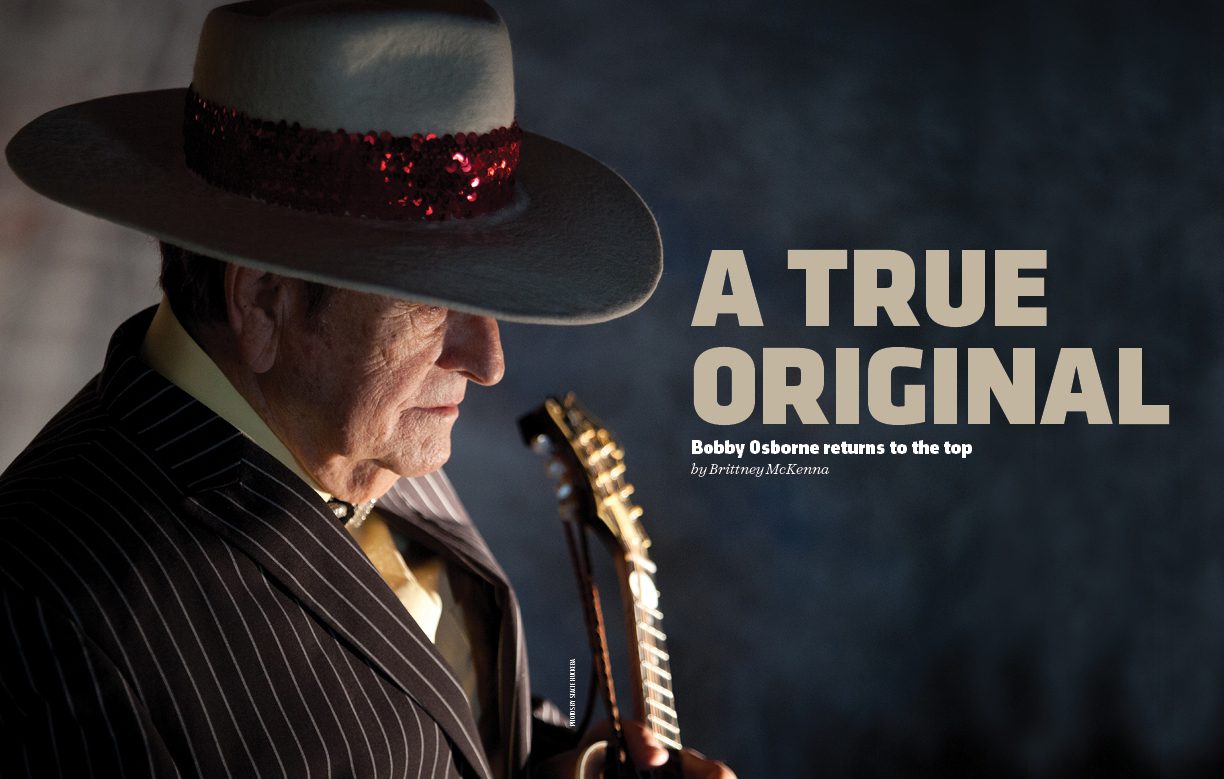

When people talk about Bobby Osborne, there’s one word that comes up time and time again: legend. A godfather of modern bluegrass, that tight-knit community speaks of him with the same reverence as rock ‘n’ roll fans might of Jimi Hendrix or Bob Dylan. Over the course of his more than 60-year career — as part of the Osborne Brothers during their heyday in the 1960s-70s, with their massive hit “Rocky Top” in 1967, and more — Osborne has created some of the genre’s most important works and paved the way for generations of progressive bluegrassers to come.

And he’s not done yet. With living legends, it can be tempting to wrap a bow around their heyday years and call it a legacy. Osborne, however, has other ideas. Even after his brother Sonny retired from music and the Osborne Brothers were, in some ways, no more, Bobby kept playing. He kept touring and releasing music, and he kept thinking about his next project even when he wasn’t sure he’d ever have the chance to release a new album. Without a record deal, he grew content with the fact that, though he wasn’t done with music, music might be done with him.

That all changed when he joined forces with celebrated musician, producer, and Compass Records co-founder Alison Brown. The two initially connected while working together on Peter Rowan’s 2013 album The Old School, on which Osborne contributed vocals. During their time together, Brown and Osborne discussed the possibility of his putting out a new album with Compass, a prospect that had Osborne feeling optimistic.

Seated in a conference room in Compass’ office on Music Row, Osborne says, “I really thought that that was about it, that I wouldn’t record anymore. Alison came along and saw something that she wanted to do, I guess, and that was put out a CD and bring me back to life.”

In person, Osborne is as warm and affable as his singing voice is clear and smooth. His son Bobby Jr. sits on the couch across from him, and the elder Osborne makes sure to introduce his son and share a little about his musical accolades, too. This generosity of spirit is another frequent talking point around Osborne, and is part of what initially drew Brown to work with him. That, and the fact that he can still out-sing just about anybody, even in his mid-‘80s.

“In the course of the sessions, he happened to mention that he’d really wanted to do another project and didn’t know if he’d have the opportunity to do another record, which I thought was a shame because he sounded great,” Brown explains in a later conversation via phone. “It took a few years of thinking and figuring out how to get the economics of it to make sense.”

Brown pulled together funds from a grant awarded by the FreshGrass Foundation (the 501(c)(3) that also publishes No Depression), an online crowd-funding campaign, and from Compass itself to lay the groundwork for what would become Original, Osborne’s first solo album since 2009’s Bluegrass & Beyond. Start-to-finish, the process took several years, though Brown notes that once the financial matters were settled, everything else “fell together really organically.”

“It was just so easy working with Bobby,” she says. “He was so open to trying anything, and just so giving and generous in the process. It made it a real joy.”

Brown ended up playing a major role in the record’s direction, helping to choose the tracks Osborne would sing. One of the first of those was “Country Boy,” a pastoral ballad penned by Arthur Hancock that resonated deeply with Osborne and his east Kentucky roots.

“Alison had sent me a song called ‘Country Boy,’ which is on the CD, and I thought it fit me pretty good,” Osborne says. “Then we had a meeting at the studio here and she had some songs picked out and I had some. I think she knew exactly the type songs that would be good for me to do. I just picked out some that I had heard that I would like to do.”

The resulting collection spans decades and defies genres. It also features an incredible roster of guest musicians. “Make the World Go Away” is a stirring cover of the 1965 Eddy Arnold tune and features Sierra Hull and Vince Gill. A barn-burning version of the show tune “They Call the Wind Maria” enlists Brown, Hull, and Stuart Duncan. And, in a move sure to rile traditionalists, it includes a show-stealing cover of the Bee Gees’ cut “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You,” off their 1968 album Staying Alive.

“In some ways, I feel like [Original] plays to both sides of his legacy,” Brown says. “There are some more traditionally rooted themes on the record, something like ‘Country Boy,’ maybe. But there’s still the cover of the Bee Gees tune, which seems very Osborne Brothers in terms of reaching outside the box for material, which those guys always did.”

In fact, members of the Recording Academy recognized this combination of traditional and contemporary influences and bequeathed Osborne with a Grammy nomination for Original, in the category of Best Bluegrass Album. He received the news just shy of his 86th birthday, while in the hospital with three broken ribs after falling in his home. While Osborne has been nominated in the past for collaborative work with the Osborne Brothers and with Rhonda Vincent, it’s his first nomination as a solo artist, an accomplishment made all the more precious when considering that Original almost didn’t happen at all.

When considering how Original fits into the broader narrative of his legacy, Osborne is all humor and humility, explaining that earlier incarnations of the album’s track list included songs by more traditional country and bluegrass figures.

“Well, I was glad she picked out the newer-type songs for me, because I got to thinking, ‘You know, there ain’t no point in me trying to sing George Jones songs, or Merle Haggard,’” he says with a chuckle. “Once those guys have finished with a song, that’s the final on that, you know?”

Of course, plenty of folks would say that a Bobby Osborne vocal is also the true “final.” That crystalline tenor has inspired countless singers since he and Sonny first gained popularity on the bluegrass circuit performing as the Osborne Brothers in the ’50s and ’60s. In particular, Bobby Osborne’s trademark “high lead” style of singing inspired countless singers in bluegrass and beyond.

As part of the Osborne Brothers, Osborne shaped the genre not just with his singing voice but also with his playing. One of the planet’s best mandolin players, Osborne (along with Sonny) was also responsible for ushering in a new incarnation of bluegrass that made room for amps, drums, and once-unorthodox arrangements like the addition of a second banjo.

“He’s one of the first guys that I ever listened to,” says Ronnie McCoury. McCoury, who’s known Osborne through his father, Del, for years, played on the Original track “Goodbye Wheeling.” “In my opinion, there are three styles in bluegrass: Bill Monroe, Bobby Osborne, and Jesse McReynolds. And from those three, all of bluegrass mandolin comes through them, from them. His mandolin playing has been overshadowed by his singing.”

Noted bluegrass scholar Neil Rosenberg, who’s known Osborne since they played a gig together at Antioch College in 1960 and who wrote the liner notes for Original at the behest of Brown, elaborates on Osborne’s musical mastery: “ [He] set a standard, a high standard. It’s taken him a long way and it’s inspired a lot of other people. And his mandolin playing. He did some things that the earliest mandolin players hadn’t thought of, and he added a lot to the way in which people think about the mandolin and play the mandolin.”

Innovations like these (not to mention a little song called “Rocky Top”) made the Osborne Brothers one of the most influential acts ever to set foot on a bluegrass stage. And with Original, Osborne proves that his already storied legacy is very much still being written.

Three Chords

Born Dec. 7, 1931, in Leslie County, Kentucky, Bobby Osborne spent his first few years of life in a tiny town called Thousandsticks. Four miles from Hyden and about 20 miles from Hazard, life in Thousandsticks was as primitive as its folksy name suggests. The Osbornes didn’t have electricity, running water, or a car. Their only mode of transportation, aside from walking, was a mule, which they could take on the mountainous journey to Hyden to access electricity and purchase household goods and groceries.

“When it got dark, you might as well just go to bed, because there wasn’t nothing else to do,” he says with a chuckle. “That was the type of living it was.”

In those early years, Osborne’s father, Robert Osborne Sr., was a schoolteacher. His grandfather operated a small general store where Osborne would sometimes help out. His brother (and eventual bandmate) Sonny was born in 1937. The brothers also have a sister, named Louise.

Though the family had little access to much outside of eastern Kentucky, music was always a major part of Osborne’s life. He and his family were regular listeners of the Grand Ole Opry, using a battery-powered radio to tune into Nashville’s famed WSM radio station, a habit owed both to Osborne’s father’s love of Jimmie Rodgers and to the fact that WSM was the only station the family was able to pick up in their home in the mountains.

“I got acquainted with listening to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio every Saturday night,” Osborne says. “A lot of people back in them hills would … whoever had the biggest living room, they’d all gather there and listen to the Grand Ole Opry. Another guy on down the creek further, he had a radio that would pick up the Opry, so everybody would just go to his house and listen to the Opry on Saturday night.”

But it wasn’t until his father moved the family to Dayton, Ohio, in the early 1940s to accept a new job that Osborne, then around 10 years old, began to take music seriously. The family had electricity for the first time, and with that came an electric radio and access to more stations. When Osborne was about 12 years old, his father taught him three chords on the guitar, a small favor that would yield big returns.

“My dad always had a guitar or fiddle or something lying around the house,” he explains. “About everybody did back then, you know. He showed me three chords on the guitar. I just took it from there and I’m still going.”

It was around that time, too, that the Opry really hit its stride. Moving to the famed Ryman Auditorium in 1943, the Opry had what some consider its golden era in the years that followed, playing host to and launching the careers of country and bluegrass music royalty like Roy Acuff and Bill Monroe.

“Acuff was the first person that ever just reared back and started singing a song,” Osborne says. “On the Opry there was nothing but just … square dances and stuff like that. There weren’t any singers around. I guess the story I’ve always heard is that Roy Acuff just sang ‘The Great Speckled Bird’ or something like that and singers floated in there from everywhere after that. It just kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger.”

Inspired by those broadcasts, it would be just a few years before Osborne dropped out of school to pursue music with Sonny. The pair played regionally before Bobby was drafted into the Marines in 1951, during the Korean War. Wounded in combat, Osborne was awarded a Purple Heart before returning home in 1953, with music calling his name. While Osborne was away, his sister Louise — herself a musician — wrote a song called “A Brother in Korea,” which Sonny recorded. After an honorable discharge from the service in 1953, Osborne returned home with music calling his name.

“I had to give up [music] when I went into the Marine Corps when I was 20 years old,” Osborne says. “When I got discharged out of the Marine Corps, I went right back to what I was doing. I had to stop and get some jobs, get me a job once in a while and make me some more money. Then I’d get back into the music again.”

Osborne would dabble with odd jobs here and there, but his heart remained set on playing music. “I drove a cab for a while and drove a school bus,” he says. “I did a lot of other jobs, anything to make a dollar. I worked in a restaurant a while as a bus boy. I worked at a factory. My dad got me a job at the factory where he worked. I really got sick of that in a hurry. When I left there I made up my mind that I was going to make it in music or completely quit period.”

To say Osborne “made it” would be an understatement. The Osborne Brothers signed with MGM Records in 1956 and had success right off the bat with first single “Ruby Are You Mad.” Alongside Red Allen, they landed on the country chart with “Once More” in 1958. They performed as part of the WWVA Jamboree beginning in 1956 and played the first-ever bluegrass concert on a college campus at Antioch College in 1960.

One of Osborne’s most treasured accomplishments came on Aug. 8, 1964, when the Osborne Brothers were invited to join the Grand Ole Opry, a full-circle moment for the young boy who used to listen to Ernest Tubb on his family’s battery-powered radio in rural Kentucky. “That was the biggest thrill in the world,” he says. “I never thought I’d ever be good enough to do anything like that.”

“At that time, there was probably no one bigger in bluegrass,” McCoury says. “They were just stars. They were the stars. They had the look. They had the songs. They had the Grand Ole Opry membership. They were as big of a bluegrass star as there was.”

“The Osborne Brothers came after the first-generation guys, in a sense,” Brown says. “Not too much after. They played on the Grand Ole Opry when Bill Monroe was on the Grand Ole Opry, but they were just that little bit younger. What they were doing musically, in my opinion, really created the path for newgrass music. They were the first guys to look at what the first-generation guys were doing and tried to take it to the next place. That may seem like something very small to us now, but it was big then.”

Finding the Top

By this point, The Osborne Brothers had made it big, and there was nowhere to go but straight to the top — the “Rocky Top.”

Bobby and Sonny would record what would become their biggest hit in November of 1967. Written by songwriting team (and husband and wife) Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, “Rocky Top,” despite its current status as the state song of Tennessee and one of the most covered country songs ever written, was originally the B-side to the Osborne Brothers song “My Favorite Memory” and seemingly had no potential as a single.

“We had three songs ready to go for a session, and back in those days what we call a session was four songs,” Osborne explains. “And you tried to get those four songs in three hours, if you could. We had three that we were going to try, and we lacked one more song. So Sonny called up Boudleaux Bryant and asked if he had any songs and he said, ‘Well, I’m working on one here. It’s not finished yet.’”

That song, of course, was “Rocky Top,” though in the Bryants’ hands it was originally a slow, somber ballad. The Osbornes envisioned the track as the fast-paced Appalachian tour de force now played at University of Tennessee football games, and the rest, thanks in part to the help of a particularly prescient DJ, is history.

“Ralph Emery, who was a nighttime DJ on WSM at that time, he was playing the A-side just like everybody else,” Osborne explains. “We went up to visit him one night and he said, ‘We’ve been playing the A-side. I’m going to turn this over and play the B-side and see what everybody thinks of it.’ Him being on WSM, he went all over the country. He was one of the very few night DJs on all night long back then. He played ‘Rocky Top’ and his switchboard lit up. That was the end of ‘My Favorite Memory’ right there.”

“Rocky Top,” released on Christmas Day in 1967, turned 50 last December. Bobby and Sonny reunited at the International Bluegrass Music Association’s World of Bluegrass festival in September 2017 to perform a special anniversary tribute to the storied track. For as many hundreds of times he’s likely played the song over the past few decades, Osborne hasn’t grown tired of it yet. “I guess the last time I ever appear on the Opry I’ll sing ‘Rocky Top,’” he says with a laugh.

While “Rocky Top” is, of course, about Tennessee, it still gets at the heart of the Appalachian culture in which Osborne was steeped in his young years. As time has gone on he’s maintained a deep connection to that culture, and is something of a hero in the town of Hazard. Brown got to experience that connection firsthand when Osborne invited her to play with the Osborne Brothers during a homecoming festival in Hyden in 2016.

“I was standing backstage and someone says, ‘Look between the rift in the hills there. There’s a mule trail that takes you up to where Bobby’s cabin was where he was born,’ Brown recalls. “You could see where the family had cut coal out of the hillside to power the cabin. Those things are still there. He’s really the native son.

“To see how much his presence and his music means just in that really small context of that small homecoming festival in that shed behind the community center, I can feel that he and his music and their accomplishments on the global scale are just an incredible source of pride to people from that region. They’re really the hometown sons done good in a big way.”

Teaching and Learning

Though one could spend countless hours plumbing Osborne’s musical past, the musician himself is firmly focused on the future. As far as he’s concerned, Original isn’t necessarily his last album. As of right now, it’s just his most recent. Of course, perhaps that’s not so surprising from a guy long known for bucking conventions and expectations.

“I’m lucky because my dad is the same way, but they just don’t stop,” McCoury says of Osborne and his peers. “They keep doing what they do and they aren’t hashing the same old stuff over. They’re adventurous. They try new things. You can’t help but be inspired by that.”

With his mandolin students at the Hazard Community and Technical College, who are enrolled in the Kentucky School of Bluegrass and Traditional Music, Osborne is open-minded and forward thinking — an approach he’s maintained since accepting the job from the school’s director (and his cousin) Dean Osborne 10 years ago. In another full-circle achievement for Osborne, he teaches classes in the same building where his father taught school when he was a young boy.

Osborne only has two requirements for his students. First, they need at least some musical background, even just knowing how to play a handful of chords, akin to what he learned from his early lessons with his father. He’s less concerned with skill than he is commitment — as he says with a chuckle, “You don’t know if they wanna [play music] or go to the store and get a candy bar or something.”

Interestingly, the second requirement for the octogenarian teacher is that every one of his students needs a cell phone to record part of lessons. “I tell all my students to be sure and have a cell phone,” he says, balancing his own iPhone on his knee. “You only see each student once a week, and I know by my own experience if you learn something from somebody, about Wednesday of that following week you’ll be trying play what you learned and you already forgot it. So I request all of them to have a cell phone.”

Between his teaching and his new record, Osborne certainly doesn’t lack the will to keep playing. In many ways, Original condenses what Osborne has spent a career doing — inside and outside the industry — into one album. It showcases his preternatural musicianship, both vocally and instrumentally. Its eclectic track list shines a spotlight on his visionary open-mindedness. Its roster of guests cements his status both as a beloved bluegrass figure and as a player always open to collaboration.

Even deep into his 80s, if there’s a song to be sung, then Osborne’s gonna sing it. “A lot of people, singers especially, and players, too … you get to a certain age and you lose a little bit of interest in it, I think,” he says. “A lot of people just want to sit down and not do nothin’, I guess. But myself, I ain’t never gonna sit down and not do nothin’ until the man upstairs says, ‘You can’t do it no more.’ So that’s the way I feel about it. I’m going to do it as long as I can.”