JOURNAL EXCERPT: Inside the World of Elvis Presley Memorabilia Collectors

EDITOR’S NOTE: With Baz Luhrmann’s new film, Elvis, coming to theaters on June 24, we thought we’d share part of this story from our Winter 2019 “Vision” journal about the annual gathering called “Elvis Week” and the troves of Elvis memorabilia that can be found there. To read the whole thing, purchase the Winter 2019 issue in print or digitally here. Or better yet, subscribe to support the music journalism No Depression brings you in print and online all year long.

For a one-time preeminent dealer of Elvis Presley artifacts, Jimmy Velvet doesn’t have much to sell. It’s Elvis Week 2019, which takes place in Memphis every August leading up to the anniversary of the singer’s death, and Velvet sits alone behind a corral of folding tables in a low-ceilinged conference room of a Travelodge near the airport. The man who opened the first Elvis Presley Museum in 1978 is now 80, sporting suspenders, a soft smile, and the deferential accent of a Southern boy raised by grandmothers. He holds down a prime spot at the 41st Elvis Presley Fan & Collector Show, and his table is scattered with random items, such as Elvis-branded plastic drink stirrers and a rare live recording from the 1956 Mississippi-Alabama Fair & Dairy Show, for which he took the cover photo. Propped against the wall is an original vinyl of his own album, A Touch of Velvet, from 1968; the sleeve shows a young Velvet with his jacket tossed over his shoulder. There’s a CD featuring Velvet’s 2006 single with David Allan Coe called “Did You Know Elvis?”

Velvet’s main merchandise today is his 2007 coffee table book, Inside the Dream. It’s a 288-page tome featuring thousands of Velvet’s personal photos, mostly of his slight frame posing beside heroes of rock and roll and the entertainment industry, stretching back to the first photos he ever snapped — backstage in 1956 in Jacksonville, Florida, goofing around with a 20-year-old musician. Velvet’s high-school teacher, Mae Boren Axton, who also worked as a local show promoter, had gotten the 15-year-old into a Hank Snow jamboree concert at the Gator Bowl when she knew he couldn’t afford the ticket. Velvet aimed to meet June Carter, but ended up chatting with a guitar player with a dirty blond pompadour.

“After about an hour, he sticks out his hand and says, ‘By the way, I’m Elvis Presley,’” Velvet recalls. “And my first thought was, ‘What’s an Elvis Presley?’ Then Mama Mae walks up and says, ‘I see you’ve met Elvis. He just recorded my song, ‘Heartbreak Hotel.’”

This is the way all of Velvet’s stories go: One music icon leads to the next. On the edge of the frame is Velvet, a Forrest Gump-like figure who kept showing up with his camera, who straddled the line between fan and insider. Velvet had a long friendship with Presley and his family, but he also predicted the market value of celebrity artifacts. In fact, Velvet’s career trajectory is inextricably bound up with the evolution of Presley’s posthumous image and the material culture of Elvis fandom. Where Velvet is now also points to how the market of Elvis iconography is still shifting.

Big Business

The King of Rock and Roll has been dead now for longer than he was alive. In the 42 years since his death, Presley’s seedy secular sainthood ballooned among his legion fans, and the physical trappings of his performance — his replicated image, his costumes — gained nearly as much influence and ubiquity as recordings of his voice. In the coming months and year, we can expect a renewed wave of Elvis representation in pop culture, including a feature film directed by Baz Luhrmann and starring Tom Hanks as Colonel Tom Parker [Elvis opens in the US on June 24, 2022].

Undeniably, Presley combined roots music, R&B, and country with undeniable pop tempos and preternatural swagger to bring something called rock and roll to the white masses; even if the casual listener couldn’t hum the tune of a Presley hit, they’d likely able to identify the black pompadour and sideburns, the curled lip, the gyrating hips, the flamboyant white jumpsuit. The image has been sold on merchandise from velvet canvases to porcelain plates to trashcans. Elvis was always big business, but his fans began this material-based devotion organically.

In early 1978, Jimmy Velvet and his band were playing a two-week residency at a Ramada Inn, also near the Memphis airport. In between sets, he was watching the local news when he heard that the city was considering opening a museum dedicated to Presley.

“I thought, ‘Considering? You should’ve already been building it!’” Velvet recounts. “It wore on my mind. So in the middle of my next set, I announced that this would be my last show. I said, ‘I’m going to open an Elvis Presley museum myself,’” he laughs. The next day, Velvet says he received permission from Presley’s father, Vernon, with whom Velvet was close. In June, 10 months after Presley’s death, Velvet opened the Elvis Presley “Mini Museum” directly across the street from Graceland, which would not open to the public until 1982. Velvet’s museum featured 21 items from his own collection — jackets and jewelry that Presley had given to him over the years. For $1 admission, Velvet took eight guests at a time into the small back room, where they could examine the precious relics in three display cases.

By the mid-1990s, Graceland had become a major tourist destination, the second-most-visited home in the United States after the White House, hosting 600,000 guests per year — and helping Elvis Presley Enterprises (EPE) escape bankruptcy. EPE has also stringently controlled Presley merchandise, the use of his name, and his mass-produced image — barring, for example, any image of an overweight Presley.

“If you haven’t been to Graceland recently, you haven’t been to Graceland,” said Joel Weinshanker, managing partner of Graceland Holdings LLC, in 2017. The latest majority owners of EPE have made huge strides in updating the Presley brand for the contemporary era, expanding into new properties on Elvis Presley Boulevard, including a $45-million, 200,000-square-foot entertainment complex. The vibe is a cross between Hard Rock and Disney World, where you can observe and consume a swept-clean version of Presley’s loves and triumphs.

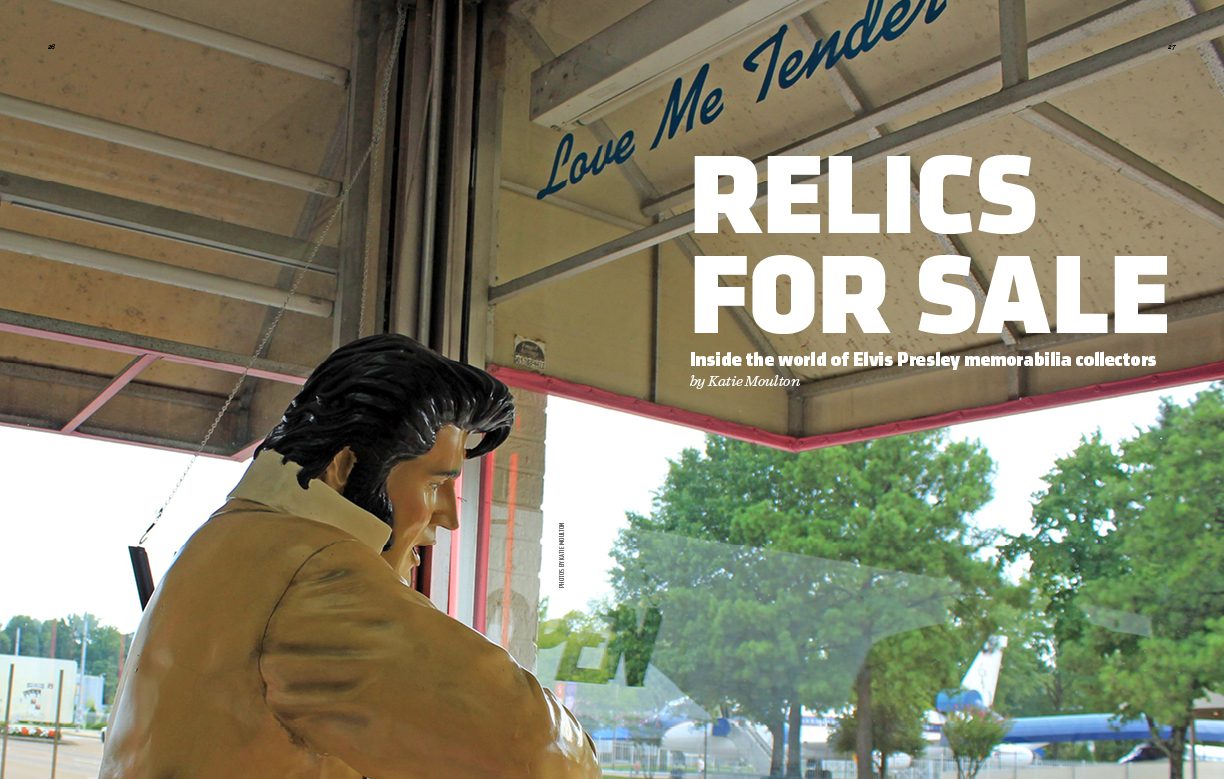

As for the shopping center across from Graceland that once housed Velvet’s first museum and other independent souvenir vendors, EPE long ago purchased it and shuttered the shops, except for one, which it owns. The lot serves as blocked-off employee parking. It’s an obvious metaphor for the chasm between independent vendors and the estate. In graying hotel lobbies along Elvis Presley Boulevard, devotees who built this specific fan culture expressed alienation as EPE successfully consolidates the Presley brand for a new era. These were the fans who traded photos through the mail, hunted down collectibles, created shrines in their homes, and started grassroots fan clubs like the one that sponsors the Candlelight Vigil on the anniversary of Presley’s death. According to historian Erika Doss, “Fans repeatedly say that by collecting and displaying Elvis memorabilia they are ‘taking care’ of Elvis, keeping his memory alive and rescuing him from historical oblivion.”

Presley has long functioned as the spectacular receptacle of mass projections of what it means to be American, to search, to dream, to struggle, to transcend, to live excessively, creatively, and destructively. As the Elvis fans who have kept his memory alive through these images and collectibles pass away, it’s becoming more and more muddled which version of the star will be valued.

“Elvis fans are loyal and they’re good,” Velvet says. “They’re not always the prettiest, the sexiest, or dressed the most beautiful, but inside is what matters.”