LIVE REVIEW: Bob Dylan and Neil Young in Hyde Park – July 12, 2019

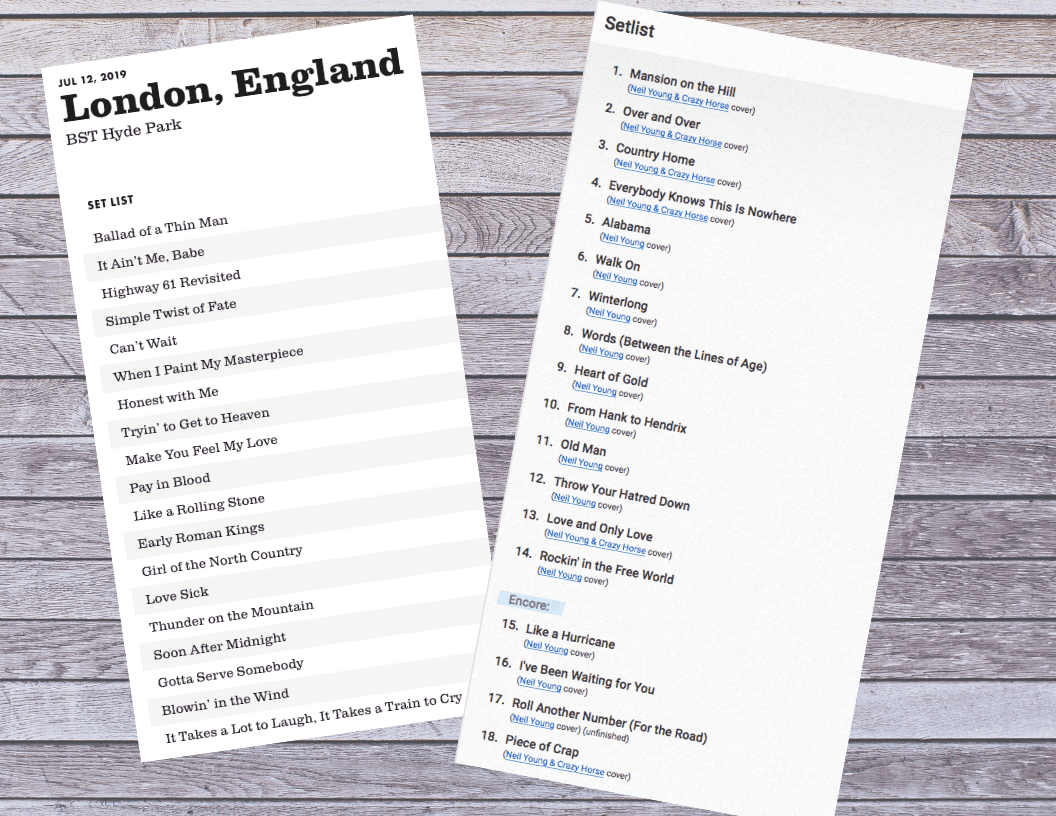

Setlists from Bob Dylan (left) and Neil Young from Hyde Park on July 12, 2019.

I am sure that you have been in this situation before. You have two friends and you love them both, but for almost completely different reasons. Taken individually, there’s no problem, but you worry about how it’d feel to see both of them at the same time in the same place together.

One of your friends is upbeat and soulful. He appeals to your sense of hope and optimism. You like it when you’re with him because you feel better when you see the world like he does. You understand and forgive that his vision is selective.

You love your other friend just as much, but he can be a bit of a downer at times and a lot of your other friends simply don’t understand him. The way he describes things, you’d swear the glass was always half empty. He’s probably not wrong, but you’re not always up to hearing what he’s got to say to you. When he’s on, he’s brilliant company and he always gives you a new way of looking at things.

Going to see Neil Young and Bob Dylan at Hyde Park in London last Friday was a lot like trying to find a place of equilibrium between those two friends. It was a sunny day and a sense of occasion could be felt in the air. Everyone was in a good mood. Friendly conversation and laughter could be heard everywhere. Most of the crowd appeared to be middle aged or older, and like me they had probably been listening to both artists for decades.

It goes without saying that both Neil Young and Bob Dylan are seasoned performers with huge back catalogs and impressive repertoires. Beyond that, one would be hard pressed to think of two iconic artists who had more distinct ways of interacting with their music and fans.

Neil Young performed first, supported by Promise of the Real, his most frequent touring band of the last few years. Much has been written about how the band, fronted by Lukas and Micah Nelson, Willie’s sons, has given Young a new focus and lease on life as a live performer. Clearly invigorated by his collaboration with the band, Young was in very fine form at Hyde Park. The deep intuition and reverence Promise of the Real communicates for Young’s music was evident in every song. Seasoned performers themselves, each member of the band displayed the chops and understanding to create the perfect musical context for songs from every phase of Young’s half-century career. The devotion the band members have for Young is palpable; their interchanges are intuitive, physical and kinetic, with Young acting as both mentor and bandleader.

Smiling all the way through, Young was clearly delighted by the aural landscapes Promise of the Real created for him to drop down into. Together, they created a sonic environment that preserved the original integrity of the songs, while at the same time imbuing them with a vitality and relevance that few veteran artists ever reach. Much of this had to do with the material Young and his band chose to perform. Many of the songs they played, such as “Winterlong,” “Everybody Knows This is Nowhere,” “Words (Between the Lines of Age),” “Walk On,” and “Alabama,” are songs that he has either never played before in concert or that have been absent from his set list for decades. When I asked Lukas Nelson about this a few years ago, he told me that the setlist often reflects his band’s favorite Neil Young songs, further demonstrating the give and take between the artist and his music protégés.

Taken as a whole, Neil Young and Promise of the Real’s performance at Hyde Park was the perfect example of how to play to a huge audience of people. Unlike his co-headliner, Bob Dylan, Young respects that people have expectations of him and he can be a crowd pleaser without ever diminishing his artistic integrity. Throughout the set, he effectively balanced his more sonically challenging material with acoustic classics like “Heart Of Gold,” “Old Man,” and “From Hank To Hendrix,” each of which was presented with reverence and care.

Lukas Nelson’s banjo accents on “Old Man” were gorgeous and took everyone back to Young’s early ’70s arrangement of the tune. Micah Nelson’s piano on “Words” was stellar and pushed the song in new directions, while the rhythm section of Corey McCormick on bass, and Anthony LoGerfo and Tato Melgar on drums and percussion recalled Crazy Horse in their prime.

But the concert went well beyond a simple recreation of classic material with younger band members doing most of the heavy lifting. Anyone who doubted that Young was still capable of playing at the top of his game only had to hear the delicate, exploratory solos he conjured on “Words” and “Like a Hurricane” to dispel that mistaken notion. He remains a unique musical force whose phrasing expresses a voice and tone unmatched by any other player of his generation.

Concluding their set with exuberant singalong versions of “Rocking in the Free World” and “Piece of Crap,” Young and Promise of the Real’s performance was everything a stadium show should be. Beautiful and true from beginning to end, Young’s songs of hope and love, truth and optimism left everyone feeling good and thinking that maybe the world wasn’t quite as hopeless as we thought. Clearly, Young’s show was going to be a hard act for Bob Dylan to follow.

Thankfully, Dylan was clearly untroubled by any expectations or comparisons that Young’s performance may have created. Dressed in a black hat, white jacket, and striped trousers, Dylan grinned and shimmied like a carnival snake oil salesman as he took the stage. As his fans have come to expect, he chose not to acknowledge the crowd as he sat down at the piano and got to work. While he doesn’t explicitly share Young’s crowd-pleasing ethos, Dylan nevertheless acknowledged the importance of the occasion by offering a set list that diverged widely from his standard fare. A dark and brooding, percussively driven “Ballad of a Thin Man” set the tone early on as he moved his way through one of the most uncompromising sets of music anyone in the audience had ever heard. He followed with an astonishing staccato version of “It Ain’t Me Babe” that syllable-by-syllable spiraled into a resignation and despair so thick that by the end of the song it was hard to breathe. He rescued the crowd from emotional collapse with a hard rocking version of “Highway 61” that pulled everyone from the brink before Dylan and the band glided into lovely versions of “Simple Twist of Fate” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece.”

As is sometimes the case at a Dylan concert, by the time he and the band dug into newer, more challenging material like “Can’t Wait,” “Trying to Get to Heaven,” and “Honest With Me,” a sizable percentage of the crowd had already given up and wanted it all to be over. Those who said, “He’s lost the plot,” “Oh my God, someone pull him off the stage,” or “Why does he think he has the right to charge people to hear him mangle his old songs,” really, as the opening song suggested, didn’t understand what was happening. His seeming irreverence notwithstanding, Dylan’s performance was anything but a walkthrough. Instead, it was like a master class in reinterpretation to hear Dylan engage with songs that have been sacrosanct and untouchable standards for decades now. Unlike Young’s adherence to faithfully performing his old classics in their original arrangements, Dylan’s renditions bore almost no resemblance to their original structures. It didn’t always work. His performance of “Gotta Serve Somebody,” with completely rewritten lyrics, was spellbinding, as was the set closer, a downtempo reading of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” But other rearrangements, such as the gospel-infused, stop-and-start reading of “Like A Rolling Stone” and a baffling take of “Blowin’ in the Wind” were not nearly as compelling.

There were few moments of levity in Dylan’s set. My companion at the show summed up his experience by saying he didn’t feel that he was at a concert as much as thrust into the presence of an angry prophet whose purpose was to hector the audience and extract a promise from them to try harder and “do better.” Dark and apocalyptic from beginning to end, there were no suggestions from Dylan that “we shall overcome.” Instead, there was the feeling that we’d all better get ourselves right with God and prepare to meet our makers. Mid-set songs like the astonishing “Pay in Blood” and “Early Roman Kings” did nothing to dispel this notion.

After Dylan’s performance ended and the crowd began to file out of Hyde Park into the London night, I could hear people arguing about which artist gave the better performance. “Good old Neil” or “Old weird Bob”? As tempting as it may be to weigh in on such a debate, in the end, any conclusions would probably prove irrelevant. As artists, they’re not really comparable. Each of their performances was powerful, unique, and incapable of replication. As time passes, even the naysayers in the audience will likely come to appreciate their good fortune to have been present at such a historic event. Bob Dylan and Neil Young are irreplaceable, and it goes without saying that we will never see their like again.

To comment on this or any No Depression story, drop us a line at letters@nodepression.com.