New Documentary Tells Story of the ‘Big Family’ of Bluegrass

Photo via KET

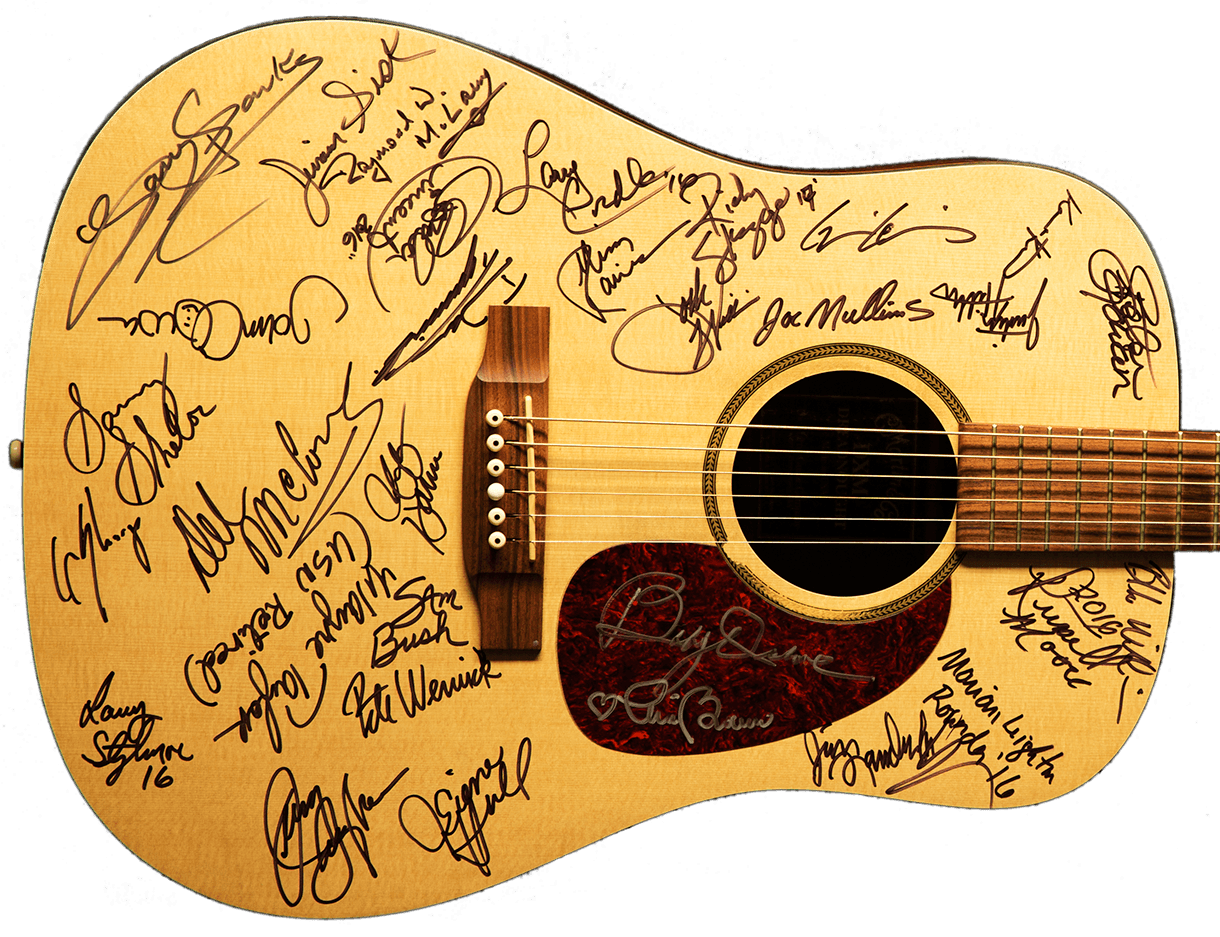

At the beginning of Big Family: The Story of Bluegrass Music, over footage of bluegrass artists autographing a Martin guitar, the voiceover shares a quote from Bill Monroe that could serve as a thesis statement for the documentary: “Bluegrass has brought more people together and made more friends than any music in the world.”

As the film, a Kentucky Educational Television (KET) production that debuts on most PBS stations this Friday at 9 p.m. ET, dives into bluegrass music’s roots, history, and progression, music’s power to bring people together is front and center. You see it in vintage photos of families and neighbors playing music together on front porches, and you see it in footage of fans and artists mingling at festivals across decades. You also see it in the filmmakers’ travels to Japan, which has a thriving bluegrass scene and is home to one of the longest-running bluegrass festivals in the world.

“While filming at the Rocky Top music club [in Tokyo], we felt so warmly welcomed,” says co-producer Matt Grimm via email. “Despite not speaking Japanese or having ever visited before, it was as if we all had known each other our whole lives. The close-knit bluegrass community there was so pleased we had come and was deeply appreciative. Memorabilia decorates the club’s walls from trips Japanese fans have made to Owensboro (home of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum) and Rosine, Kentucky (Bill Monroe’s homeplace). Photos and autographs from American musicians who have played the venue also cover the walls. We were over 6,000 miles from Kentucky and yet we were surrounded by so many familiar sights and had so many new friends.”

Grimm and co-producer Nick Helton started working on Big Family in 2016, gathering their first interviews and footage at the International Bluegrass Music Association’s annual World of Bluegrass conference and festival in Raleigh, North Carolina, that year. The film visits several other locales, either in person or through archival photos and videos, including Chicago; Washington, D.C.; Nashville; and the FreshGrass Festival in North Adams, Massachusetts. (FreshGrass and No Depression are both part of the nonprofit FreshGrass Foundation.) As actor, banjoist, and Bluegrass Situation co-founder Ed Helms narrates, the storyline is supported by commentary from more than 50 current bluegrass artists, including Chris Thile, Peter Rowan, Laurie Lewis, Jerry Douglas, Sierra Hull, Kaia Kater, and Ricky Skaggs.

“We wanted to combine telling the history with performance excerpts and a chorus of interviewees from across the genre,” Grimm says. “We also wanted to underscore the larger societal factors that influenced the evolution of the music. We hoped this approach would result in a film that had broad appeal.”

Indeed, while the film covers familiar ground like the addition of Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs to Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, radio shows like the National Barn Dance and the Grand Ole Opry, and the newgrass movement, it also showcases African American blues guitarist Arnold Shultz’s influence on a teenaged Monroe, the banjo’s origins in Africa, and women musicians across the history of the genre.

“It’s part of the history,” Helton says, “and I think a lot of people don’t know about those elements in bluegrass music. The fact that the banjo came from Africa surprises a lot of people.”

The storytelling in Big Family is augmented, of course, by songs and images from across decades. Some of the footage was easier to come by than others, the filmmakers said.

“We combed through so many archives looking for gems,” says Grimm. “Bluegrassers will likely recognize some of the photos included, but we hope some will be new to people, too. For instance, a photo of the Osborne Brothers performing at Antioch College in 1960 — that was the first appearance of a bluegrass band at a college.”

Adds Helton: “At times, we felt like investigative reporters tracking down photos and footage. There is a short film clip of Jerry Garcia playing banjo as a young man that took some serious digging to acquire. I ended up locating someone in California who had played with Garcia in a bluegrass band and acquired the rights to that footage. The 1965 Fincastle, Virginia, bluegrass festival footage was also a great find. That was the very first multi-day bluegrass festival. It was partially filmed by a local news crew. According to one source, the news crew was called away to cover a car crash and didn’t film the entire show.”

At the end of Big Family, as some of the folks who carry the bluegrass torch today look into the future and remark on the connective power of the music across country and rural lines, socioeconomic lines, and, increasingly now, gender and racial lines, the guitar from the film’s opening makes another appearance. Helton admits it was a bit of a last-minute idea: He found a used Martin on Craigslist the day before leaving for Raleigh for the first round of interviews in 2016, and Grimm thought to film the interviewees signing it.

“As the theme of Big Family started to materialize, the autographed guitar started to represent that family,” Helton says. “During the editing process, it became the perfect footage to bookend the film and became the obvious choice as the singular image to represent the film’s theme.”

In a way, that guitar, now on display at the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Owensboro, Kentucky, also represents the bluegrass story itself. Neither came to be through careful planning or a clear line on a map. Rather, one idea led to another, and people coming together to tell stories and share emotions created something that resonates through time.

Big Family: The Story of Bluegrass Music airs on most PBS stations Friday, Aug. 30, at 9 p.m. ET. Check local listings. To comment on this or any No Depression story, drop us a line at letters@nodepression.com.