"Woody Guthrie's Wardy Forty," by Philip Buehler in Collaboration with Nora Guthrie and The Woody Guthrie Archives

Review and interview by Douglas HeselgraveWhen Nora Guthrie invited me to call her at her home to talk about ‘Woody Guthrie’s Wardy Forty’, I took it as a good sign that Woody’s daughter and the director of the Woody Guthrie Museum and Archives was beginning to slow down a bit and take a well-deserved rest. When she contacted me a half hour before our scheduled conversation from her office in the archives – and not her home - I could see that nothing had changed and even though it was Thanksgiving, Nora was busy filling out orders and preparing for the release of two new CDs of Woody’s music to go along with the other centennial tributes including the massive ‘American Radical Patriot’ box set and the recently discovered novel ‘House Of Earth.’ When I asked Nora if she’d like to talk another time, she laughed and said ‘If you’re waiting for me to have free time, I don’t know when that would be. The centenary of my dad’s birth is just like an Everready battery. I keep thinking that’s it, we’re out of juice, but it just won’t stop. Now, what is it that we’re going to talk about today?’

Most people reading this are aware that Woody Guthrie suffered from Huntington’s disease, a rare hereditary condition that gradually sapped his energy and caused him to lose control of his motor functions. The first signs of the disease appeared when Woody served in the merchant marine during the Second World War, and gradually became so severe that he was institutionalized at New York’s Greystone Part State Hospital in 1956. He stayed there until 1961 at which time he was transferred to The Brooklyn State Hospital. He stayed there for five years before moving to the Creedmore Psychiatric Center where he spent his final days.

Parts of Woody Guthrie’s life story have been told so many times that they have become indelibly woven into the fabric of musical mythology. Woody often wrote of his early days in works such as ‘Bound For Glory’ and the events described in his songs are often treated as autobiography to such an extent that they have become inseparable from his life in many people’s minds. The public Woody was brash, impulsive and idealistic. The public Woody was strong, resolute and wouldn’t back down. It’s a very appealing image that has allowed Woody’s spirit to live on, so it’s understandable that when Woody ‘fell’ and spent a decade and a half in the hospital, such an event may have seemed incongruous with the image of the flinty old Okie that had been painted in such broad strokes by folk music mythologists. As a result, these years of Woody’s life have been all but passed and glossed over, with the only reoccurring story to emerge from those years being how a very young Bob Dylan would regularly visit the ailing singer at his hospital bed.

Other than that story that served to launch a whole other mythology, it’s as if to most people the years of Woody’s illness were a dark time where nothing happened. It was as if a propriety curtain had been drawn over his life. This oversight is something that had troubled Nora for years because she’d always felt that period of her father’s experience was much more complicated than what most biographers had previously indicated. Even though he was very ill, he continued to think, work and create a lot during certain periods of his residency at Greystone Hospital.It’s a story that’s needed to be told for a long time, and the opportunity finally arose when Philip Buehler, an American photographer who specializes in photographing ‘modern ruins’ contacted the Guthrie family when he discovered that the abandoned Greystone Hospital – a place he had broken into and extensively photographed – had once been Woody’s ‘home.’ When they got together and Nora saw Buehler’s photographs, she recognized that the evocative images he captured would perfectly complement the letters, family photographs and reminiscences from the period that were housed in the Woody Guthrie Museum and Archives. ‘Woody Guthrie’s Wardy forty – Greystone Park State Hospital Revisited’ is the result.

Here are some excerpts from my conversation with Nora Guthrie about the book: DH: Were you aware of Philip Buehler’s work before you collaborated on this book? I’m wondering if he was a Woody Guthrie fan who went looking for Greystone or if your coming together was some kind of happy accident.Nora: No. Philip had been photographing old abandoned buildings since he was a teenager. It’s a really quirky love of his. What I love about the photos is that nothing has been photoshopped. A lot of times when you see other books like this there’s been a lot of retouching going on. What you see in these photos is exactly the way the place looks today. Those amazing yellows, greens and blues you see in the peeling paint are from oxidation.DH: I was going to ask you that. The colour is glorious and so evocative. It comes off as hyper-real, disturbing.

Nora: I know they’re beautiful. These photos fit in with Phil’s other work. You know, he found Greystone on his own and became interested in it. He snuck into the building. It had already been abandoned for many years. He took some photos and went home to do some research. He was Googling information about the hospital and he discovered that Woody Guthrie had stayed there. All he knew about Woody was that he’d written ‘This Land Is Your Land’

DH: The images resonate with a certain kind of purity. What I mean by that is the photos are not tilted towards manipulating any kind of poignancy that has to do exclusively with Woody.Nora: That’s why I trusted him and wanted to work with him because I knew that he was innocent and not trying to ride on Woody’s coat tails or anything like that. He didn’t even contact us to do anything for a long time. He contacted the archives to ask if Woody Guthrie was at Greystone, but he’d taken the pictures already for his own reasons. Eventually, when we connected, I went to look at the photographs out of interest because it was a place I’d known well as a child. I went there almost every weekend. Phil came to me with these photos and the minute I saw them, I was so impressed with the photography and I thought that it would go so well with the body of work I had from Woody’s hospital years. I always felt that he had been written off too early in life. Most of the books have this psychology in the writing that goes ‘he got Huntington’s’ but no one ever went into ‘what’s fifteen years in a hospital like?’ for people like Woody Guthrie. I had been waiting for an opportunity to tell that story in some way. I wanted to give it a very sensitive treatment and when I saw Phil’s pictures, I thought that this was a great window of opportunity for me to begin releasing some of this material.DH: When I look at the photographs, they’re so evocative and empty. I feel like they suggest a sad story. It’s hard to get away from a sense of longing when I look at them. Was the hospital like that when you visited it? I don’t mean was it falling apart, but do they convey the feeling you had when you visited your dad there?Nora: I certainly remember the building in its time, but actually the eeriness of the photos captured how I felt. I always felt eerie walking through the hallways. My dad was in a ward with about fifty other patients and they were psychiatric patients. He wasn’t but they didn’t know where else to put him. There were no wards for hereditary diseases. I remember that when I visited him, his bed was at the very end of the aisle. I walked so carefully, but my mother literally pranced down the aisle. Talk about an Everready battery! She was so chipper and kind. She knew that everyone there had it tough, so she saw it as her job to say ‘hello! How you doing Joe and Al or whatever to everybody! We’d walk behind her scared shitless! We kept asking ourselves how she could be so nice and friendly to these people. It was terrifying! Finally, she decided that it might be better for us to bring Woody out of the ward than to bring us into the ward. So, after she decided that, as much as possible, we’d wait outside for Woody under the Magicky tree. DH: Some of the most poignant and touching archival photos in the books show you, Arlo and your dad sitting under the tree. They make perfect sense when juxtaposed with Philip’s photos.Nora: My dad would come out when he was well enough and we’d have a picnic. She would try to make it more of a family outing as opposed to visiting him in the hospital.DH: How old were you when Woody first went to the hospital?Nora: I was seven.DH: I know this is a difficult question because it was your life and it can’t have been any different, but do you have any sense of how visiting Greystone affected you?Nora: (laughing) I’ve never been in a hospital since. I try to stay very healthy. In a way, that’s not true because the result is that I’m actually very comfortable in hospitals. It’s a two-sided coin. If I have to be in the hospital to visit someone, I’m not terrified to go there anymore. I know a lot of people don’t go to hospitals. When my dad was in the hospital, a lot of people couldn’t visit him there because of their own issues. I’m talking about close friends. I can slip into hospital mode very easily. I know how to be Nurse Nora when the time comes.You have to remember that there was a real stigma about Huntington’s in the 1950’s and my mother was very protective of him. Things have changed since then and Huntington’s has become like a signpost for genetic research. But at the time, she didn’t encourage people to visit Woody in the hospital. She didn’t want strangers to see him like that. She knew Woody would be upset. She didn’t just want people stopping by at his ‘death bed.’ Some people were sensitive. It came down to she only wanted people around who could be helpful. She needed people who knew that he was still thinking and working when he was in there. She protected him so well. She’d take him home when she could – wash him and his clothes, give him a smelly bubble bath, sprinkle him with talcum powder - make him feel good so he could feel like a real mensch again. You have to remember that my mother was a working woman who was on the job six days a week. Woody was her seventh day – and on the seventh day….. (big laugh)DH: In all the biographies, there’s not much about how badly Woody was treated when he first went to the hospital. To me, these revelations are the emotional heart of your book. It really must have been so frustrating for him to appear so demented and out of control that no one believed him when he said he was a famous folk singer and that he’d written thousands of songs and a novel. Do you have any personal memories of that?Nora:I wasn’t aware at the time, but when I found the papers – particularly the medical interviews – later in life, it was startling. But, on the other hand, if you saw him, he looked awful. There was very little care. It’s just that these large hospitals, they’d leave a tray for instance in front of your bed like in any hospital. But with Huntington’s you can’t control a fork or a spoon, so half of Woody’s food would end up on his clothing or on the floor. If he was lucky, he’d get one out of three spoonfuls to his mouth. So, he lost a lot of weight because with Huntington’s you move constantly and lose a lot of calories. You can’t afford to lose a bite! My mother had to go in and pay some of the other patients to help him and make sure he got enough to eat.DH: He must have felt so undignified. Woody was a very independent man.Nora: Exactly. My mother was so protective of his dignity and there were a few people who were seriously helpful. They were the tough ones. I credit Bob Dylan as being one of those guys. He was around twenty-one, twenty-two. He was involved with him on and off for a very long time. He also visited him at Brooklyn State Hospital when he was transferred there. Bob was always there to serve. It’s true. For a young guy to be aware that he could serve an elder was quite something – and – (laughs) that was a long, long time before he wrote ‘You’ve Got To Serve Somebody.’ He served my dad. He really did. My dad really liked him. He would tell him ‘bring me this, bring me that’ and he would. He was like my dad’s personal shopper. He’d say ‘What’ya need Woody?’ Dad always said ‘cigarettes’ and Bob would come back with a case of cigarettes. He’d bring yellow pads of paper. He’d bring Bic pens and not only that, he would sing my dad all of his songs. As Bob told me, ‘he didn’t want to hear my songs, he wanted me to sing his songs and I was happy to oblige.’ It was very helpful because Bob knew every one of his songs, and if you’re on your way out like dad was, it was important to know that you’d left something behind. Bob became the Woody Guthrie jukebox. Woody would say ‘sing this, sing that’ and Bob knew all of them and would just sing whatever he asked for. Bob just gave the greatest gift that any of the young people around could bring him – in addition to the cigarettes which were really really important. (laugh)Little pleasures like that are really important when you’re in an institution. For me, all of these things he did are emblazoned in my memory and all of the bad things you can read about Bob don’t really mean anything by comparison. John Cohen of the ‘Lost City Ramblers’ was also one of those sweet guys. He was around 19 or 20 at the time. He was a really tough guy. He’d do whatever Woody asked – and you have to remember how bad he looked a lot of the time. He could sit there and stomach anything Woody dished out. He’d keep helping and he’d come back again! John and Bob mustered so much courage to keep coming back and helping. Bob would bring some friends by like John Hammond, but a lot of them couldn’t take it. One of the most beautiful stories I can share with you about Bob is that when he would bring someone, they’d notice that Woody had trouble lighting his cigarettes. It took him five minutes to control his arm enough to light it. Bob had offered to help light it once, but Woody said ‘I got it’ and Bob immediately understood. We were talking about dignity! He didn’t want someone changing his diaper so to speak. He wanted to be seen as ‘Woody’ as a father figure. He wanted to keep his dignity with these young people and I remember Bob stopping John Hammond from helping Woody light his cigarette. He was a sensitive guy. Do you know how smart you have to be at that age to realize that. Bob is a very, very soulful person. He is a very old soul. So, again when Phil came to me with his photos I realized that this was the perfect moment for me to grab so that I can share some of these stories. I know I can’t tell the whole story, but illness is very profound.DH: …and transformative.Nora: Oh yes! Fatal illnesses are very hard to talk about and I thought that the photographs of the hospital invited the telling of a twin story, there were two stories happening simultaneously. First, one of the biggest hospitals in the world is almost gone and it’s housing one of the greatest writers in the world who’s almost gone, too.

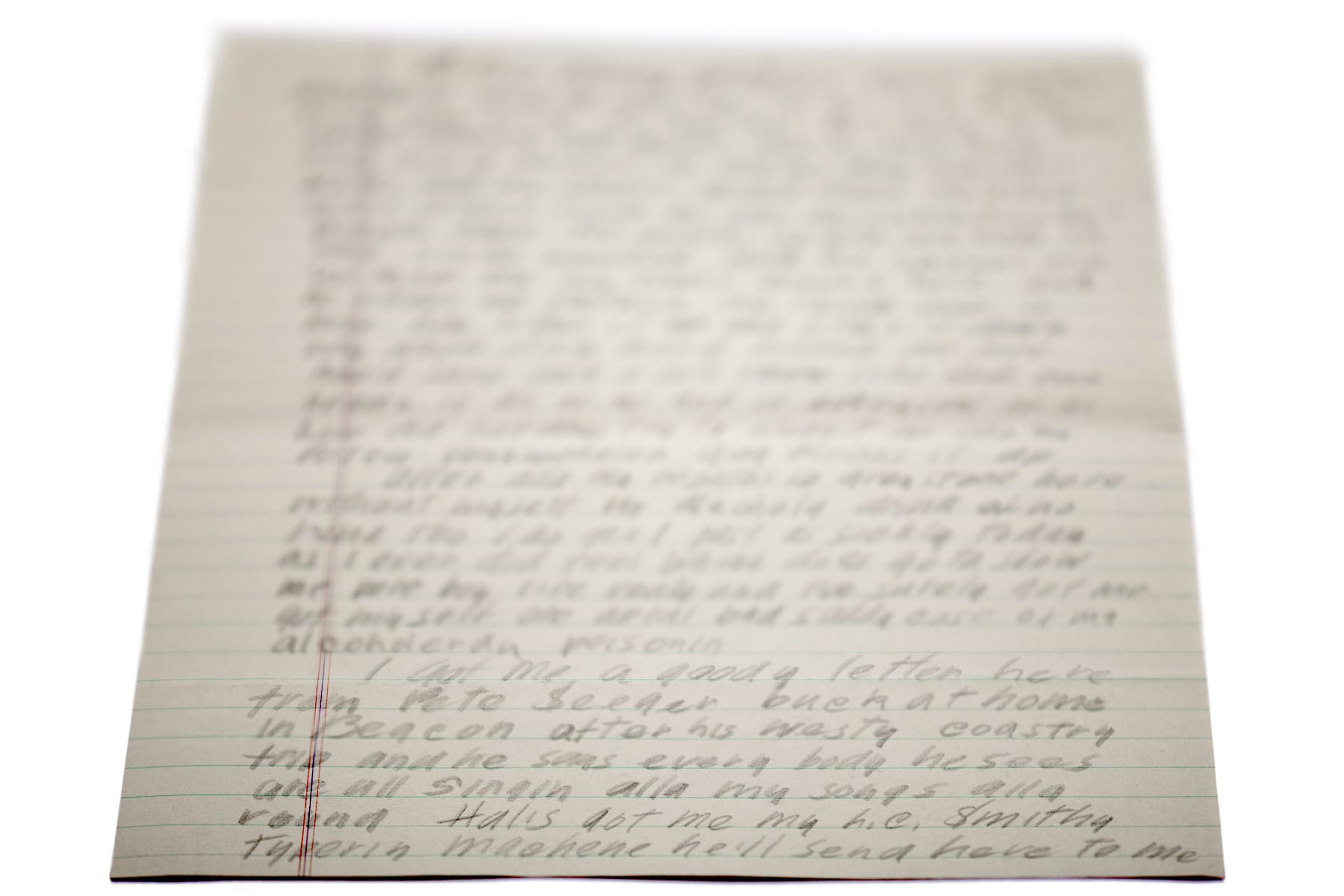

DH: Yes, the metaphors are inescapable. The photos really complement the story you’re telling. The photo that really got me was of the decaying painting on the wall, the one that shows a singer serenading a young girl. Is it possible to look at that photo and not think of your dad singing to you? Nora: Oh God! Woody poured out so much love to us. He wrote to us as much as he could and he said such beautiful, beautiful things.DH: The letters are heartbreakers. It sounds so glib to say, but it’s true!Nora: And those are only a few lines that I excerpted! I freak out whenever I read that he was such a bad dad who left home. The next book I’m going to do is about Woody as a father. I mean, how many fathers write songs for their kids? DH: There’s so much that’s fascinating at a family dynamic level. My daughter – who’s also named Nora – was very concerned that Woody signed his letters from the hospital ‘I ain’t dead quite yet.’ She told me she’d worry about me if I started signing that way.Nora: (laughing) That’s what I tell my son all the time when we argue – usually about me working too hard! But, I told you about my mother and how hard she worked. I remember actually when Woody died. I was about seventeen. The minute he passed away, my mother looked at us and asked if we were okay. When we said we were okay, she said that was good because she was going to be busy curing Huntington’s Disease! My mom was a dancer who didn’t know a cell from an atom. What a lady she was!‘Woody Guthrie’s Wardy Forty’ is available from the Woody Guthrie store. You can order it online at: www.woodyguthrie.orgPurchasing the book directly from the Guthrie family helps support the Woody Guthrie Archives.This posting originally appeared at: www.restlessandreal.blogspot.comSign up for free updates

Nora: Oh God! Woody poured out so much love to us. He wrote to us as much as he could and he said such beautiful, beautiful things.DH: The letters are heartbreakers. It sounds so glib to say, but it’s true!Nora: And those are only a few lines that I excerpted! I freak out whenever I read that he was such a bad dad who left home. The next book I’m going to do is about Woody as a father. I mean, how many fathers write songs for their kids? DH: There’s so much that’s fascinating at a family dynamic level. My daughter – who’s also named Nora – was very concerned that Woody signed his letters from the hospital ‘I ain’t dead quite yet.’ She told me she’d worry about me if I started signing that way.Nora: (laughing) That’s what I tell my son all the time when we argue – usually about me working too hard! But, I told you about my mother and how hard she worked. I remember actually when Woody died. I was about seventeen. The minute he passed away, my mother looked at us and asked if we were okay. When we said we were okay, she said that was good because she was going to be busy curing Huntington’s Disease! My mom was a dancer who didn’t know a cell from an atom. What a lady she was!‘Woody Guthrie’s Wardy Forty’ is available from the Woody Guthrie store. You can order it online at: www.woodyguthrie.orgPurchasing the book directly from the Guthrie family helps support the Woody Guthrie Archives.This posting originally appeared at: www.restlessandreal.blogspot.comSign up for free updates

Comments ()