PRINT EXCERPT: Bringing the Show Home – How Taping Connects Live Music and Fans

EDITOR’S NOTE: Below is an excerpt from a story in our Summer 2020 print issue “Tools of the Trade.” You can read the whole story — and much more — in that issue, available here. And please consider supporting No Depression with a print or digital subscription for more roots music journalism, in print and online, all year long.

There are plenty of souvenirs to take home from a concert — posters, T-shirts, records, or stickers, as well as wild-card novelties like socks, pins, keychains, and beyond. With the advent of smartphones, it’s easier than ever for a fan to snap a photo or record a video clip to keep as a memento. But one way of commemorating a concert experience has been thriving for decades, becoming a niche hobby that’s shaped fans’ relationships with an artist’s work just as much as any official efforts do. And in these days without live music, it’s more meaningful than ever.

The hobby generally goes by one of two names: bootlegging or, more commonly, taping. The latter has stuck by way of the original medium used — reel-to-reels and, later, cassettes — though magnetic tape has all but disappeared from the practice. Recordings of live shows are now made with generally less (and much lighter) gear and can reach fans across the globe within a few hours of a show ending. The “bootleg” moniker stuck around from the unsanctioned nature of someone recording a live performance, often by sneaky means. These illicit recordings sometimes made their way to vinyl, which fans sometimes purchased without the band ever seeing a dime.

The Grateful Dead is at the root of the taper scene. From the band’s outset in the mid-1960s, it developed a reputation as an inimitable live group. The Dead’s spirit of improvisation and fusion of sounds meant every show was different, which made recordings of each show sought-after and special. “The Grateful Dead sort of synthesized everything in American music one way or the other and put that together,” says Dennis McNally, who worked as the Dead’s publicist for several years and authored the band’s 2001 biography, A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead.

Dead fans took to taping with such enthusiasm that the band eventually had to enact rules for the amateur engineers. At a meeting among the Dead and their crew in 1984, the band’s audio engineer, Dan Healy, pressed for a change to the nightly scene in front of his soundboard. It had become a veritable forest of microphone stands, remembers McNally, which blocked Healy’s view of the stage and made his job significantly more difficult.

Rather than render the tapers personae non gratae (which likely would’ve backfired anyway), the Dead instead developed a system for the tapers to set up shop within a designated seating area of each show.

These days, taping extends far beyond the Dead and their more direct musical offspring. The internet has provided more avenues for tapers to share their work, including the Internet Archive and Nugs.net. The website nyctaper features recordings from Dan Lynch alongside those of a dedicated legion of volunteers in New York and beyond and now hosts thousands of recordings of acts like Wilco, Steve Gunn, Kimya Dawson, Ryley Walker, and more.

Gunn, for example, is a favorite amid some taper-friendly crowds, including nyctaper. The guitarist and singer-songwriter takes a thoroughly improvisational approach to his song development process and says it’s helpful to have a document of a spontaneous idea in motion. (He runs a smaller handheld recorder while he practices, too.)

“There are times when you kind of know that you’re sort of tapping into something, and you also know that you’re just exploring, and sometimes those lines can be blurred,” Gunn says. “So it is nice to go back and take some space from the plane and listen back with open ears.”

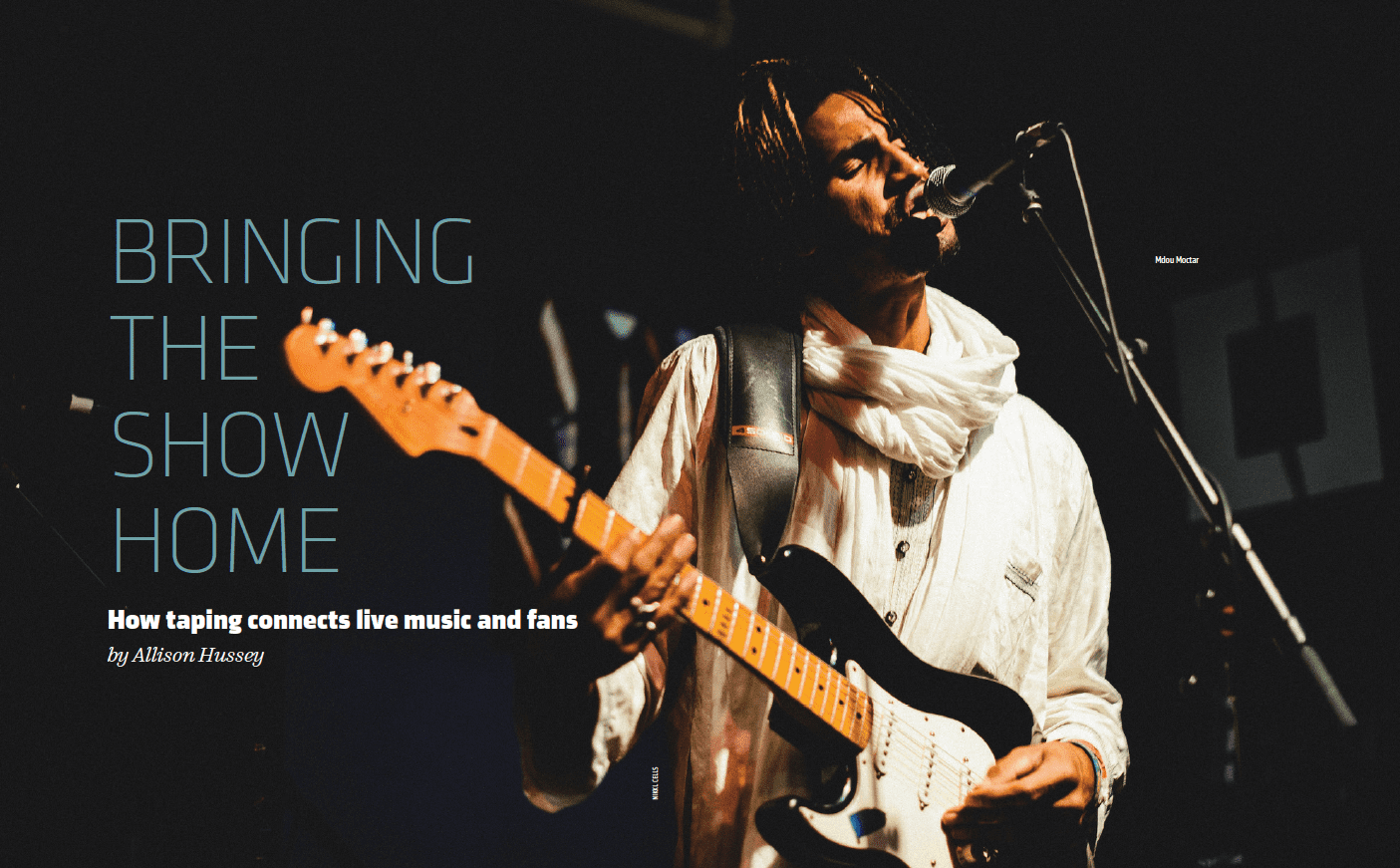

The live recordings that come out of bootlegging — sometimes even the roughest versions — can be transformative for fans and artists alike. Guitarist Mdou Moctar and his band made a name for themselves on the wedding circuit in their home country of Niger. Their reputation spread through word of mouth and recordings shared over cell phone SIM cards.

Moctar’s music, developed out of the Tuareg folk traditions in his home country, is elastic and hypnotic in any format. On stage, however, he locks with his band as they explore new corners of their compositions. As one song slips into the next, the room feels as though it crackles.

“My band and I feed off of the audience’s energy. So the more energy and excitement the people give, the more we give back, and it keeps going. I think the live recordings capture a different energy than the studio,” Moctar explains.

Of course, the taping process requires some planning on the part of its practitioners, who have to get advance permission from artists and venues. Setups vary from taper to taper, but there are a few standard elements. There are the room mics, which capture what’s blasting out of the PA to the audience, in addition to the room’s environmental sounds. The microphones themselves, slightly angled toward each other, accomplish a stereo mix, are extended vertically on telescoping mic stands to avoid capturing too much crowd noise. There’s also the board feed, wherein a taper gets sound directly from the venue’s soundboard and captures the signals directly from a band’s gear (like in many studio recordings). Depending on the show, a taper may use both room mics and a board feed, or just one or the other.

“[With room mics] you’re getting maybe some echoes, maybe some sounds that you don’t want, like a guy next to you whistling or people talking. You’ll be able to cut some of the some of the unnecessary noise that you don’t want from the straight audience recording,” says nyctaper’s Lynch.

That mix, he says, can sometimes translate into 10 or 12 extra hours of work. But it’s worth it to record the experience in a way that can re-create the magic of a live show.

“We’re trying to capture, at least audio-wise, the experience,” Lynch explains. “When the show is over, you can go back and use our recording as a way for you to remember and feel again whatever it was that was special about that particular event.”

Check out a playlist for our Summer 2020 journal, including songs by Mdou Moctar and Steve Gunn, here: