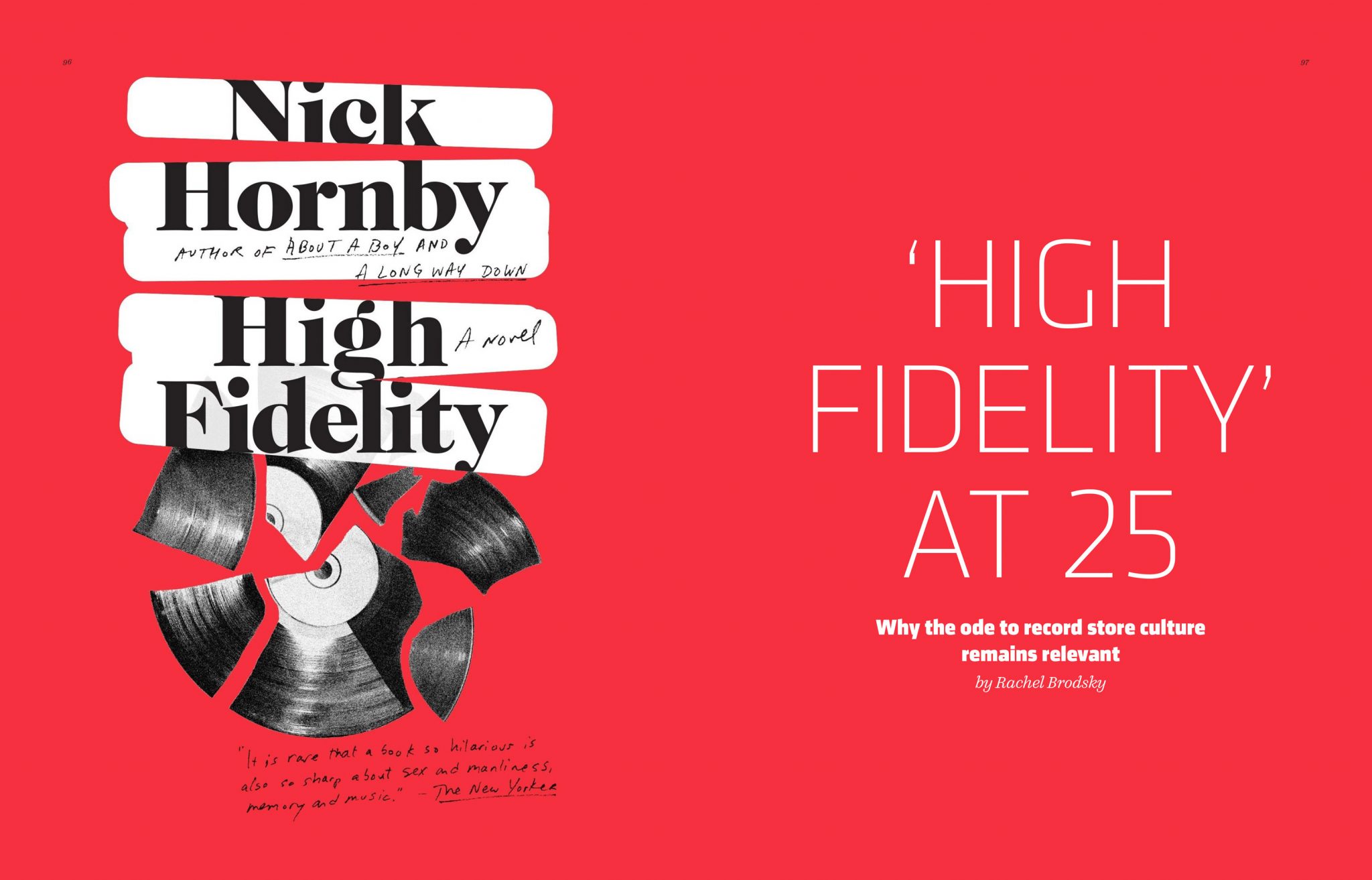

PRINT EXCERPT: ‘High Fidelity’ and Why Record Store Culture Remains Relevant

EDITOR’S NOTE: Below is an excerpt from a story in our Spring 2020 print issue “Live and In Person.” You can read the whole story — and much more — in that issue, here. And please consider supporting No Depression with a subscription for more roots music journalism, in print and online, all year long.

On March 31, 2000, Stephen Frears’ classic rom-com High Fidelity, based on Nick Hornby’s book of the same name, arrived in theaters. Prominently featuring Cameron Crowe darling John Cusack (who had arguably been playing different versions of unrepentant music snob Rob Gordon for most of his career) and then-rising comedy talent Jack Black, High Fidelity offered something of a two-pronged movie-going experience: For the vinyl enthusiast, watching High Fidelity was like walking into their favorite local record shop, replete with familiar-looking crate-digging customers and know-it-all employees. On the other hand, at the film’s heart was a highly relatable story about personal growth that just so happened to be set at an obscure Chicago record store.

At the center of said narrative was the aforementioned Rob Gordon, a 30-something music obsessive who alphabetizes his vinyl collection “autobiographically,” spends most of his time curating Top 5 lists, imagines himself getting relationship advice from Bruce Springsteen, and frequently wonders out loud why his one-sided romances fall apart (despite being an admitted “asshole”). It’s not like movies about record stores had never been made — 1995’s Empire Records continues to be a charming Gen X romp. But never had the record store been so accurately portrayed as a symbol of the approaching-middle-aged man and his failure to launch. Rob’s record store owner archetype feels so familiar that even now, two decades later, it’s highly likely that most music fans and record store devotees can pinpoint a “Rob” in their own lives — which is pretty much exactly how Hornby intended it.

Originally published in 1995, High Fidelity the novel draws from a time well before record shops were considered retail endangered species. Before music could be downloaded, curated, file shared, and uploaded into an algorithm, record shops were one of only a few outlets for music discovery. Music lovers had little other choice but to physically leave their homes and go in literal search of new music — Hornby included.

“I grew up about 20 miles outside London, and there was one record store in my town, Harlequin Records, part of a national chain,” Hornby recalls. “It wasn’t great, although I did find Little Johnny Jewel by Television in there, in a box on the counter in which everything had been reduced to 30p. Most of the time I had to get on a train and go to London, for records and clothes and even books. I used to shop in the first Virgin Records, which was above a shoe store on Oxford Street. The records were cheap, and they sold bootlegs. There was usually a tramp asleep on one of the bean bags on the floor.”

Hornby is hardly alone in such vivid memories; every music listener and musician has their own recollections of wandering into a record shop — commercial or independent — and finding new favorites. Americana performer Frazey Ford remembers how she used to get her allowance once a week and immediately head to Sam the Record Man or A&B Sound in Downtown Vancouver to go record shopping. “I think the first record I bought was Purple Rain,” she says. “That record is still the pinnacle of everything great in music. I also found Stevie Wonder, Otis Redding, and Bessie Smith.”

Former Lumineers member Neyla Pekarek also remembers early days spent finding records that would inspire her own artistry. “There was a little record store right by the house I grew up in Aurora, Colorado, called Recycle Records that I used to go to and pick out tapes and CDs growing up. I also loved Twist & Shout in Denver, and that’s still my go-to local record spot now. I had a good experience there recently when I was trying to track down this specific Miles Davis vinyl, Workin’ With the Miles Davis Quintet, and the staff was super friendly and helpful.”

Nashville rocker Andrew Leahey, who performs with his own band The Homestead and as a guitarist for country luminary Elizabeth Cook, remembers how he used to spend “an embarrassing amount of time” at his local Borders asking store clerks about songs he’d heard on the radio. “I remember asking a clerk to help me identify an oldies tune that went, ‘What’s your name, who’s your daddy,’ and he promptly introduced me to The Zombies,” Leahey says.

Indeed, as vital as record shops were to building your musical identity, at their heart was the shop’s employees, who were there as much to provide an in-person outlet to music discovery as they were to stock albums. Though High Fidelity didn’t shy away from the more absurdly pretentious characteristics of Championship’s clerks, whose collective snobbery was insecurity molded into superiority, once in a while Dick, Barry, and Rob stopped ripping on their clientele’s taste long enough to make a meaningful music recommendation. Take, for example, the scene where Rob plays The Beta Band’s “Dry the Rain” in the store, prompting a customer to ask, “Who is this? It’s good,” and Rob to reply discerningly: “I know.”

Perhaps the most enduring driver of High Fidelity’s ongoing cult status, however, is that it continues to resurface in pop culture decades after the book and film came out. In 2006, a musical based on the movie premiered on Broadway, running for 13 performances, and this spring, Hulu plans to air a TV show of the same name starring Zoë Kravitz — who, of course, is the daughter of Lisa Bonet, who played Rob’s Peter Frampton-singing fling, Marie DeSalle. Record stores may be in danger of going extinct, but from a pop cultural perspective, High Fidelity is alive and well.

Unlike the book and film, though, record stores as a shopping destination have had to work harder to retain their cultural relevance in the face of music streaming. As any musician or music industry insider can tell you, once-thriving music sales never entirely recovered after peaking in the late-’90s and early-’00s. The Recording Industry Association of America’s 2019 mid-year report projected that revenue from vinyl was set to surpass CD sales for the first time since 1986, but streaming still eclipses both.

Now that consumers can listen to any song at any time via any number of streaming services, music lovers have a lot less incentive to leave their laptops and engage with brick-and-mortar retail outlets. “What’s Happening to New York City’s Record Stores?” magazine and pressing plant The Vinyl Factory asked in 2016, looking at the domino-effect closures of longtime locations both big and small, like Other Music, Bleeker Bob’s, Tower Records, and the Virgin Megastore, which ultimately couldn’t fight rising rents and evolving music-listening habits.

Hornby, though, is optimistic about the current role record stores can still play. “The people who seek out record shops now, when there’s no need to, are more passionately committed to both the medium and the form than people who just used to go into stores because that was all we had,” he says. Those that remain, he continues, “offer a greater sense of community than they ever did.”