Remembering Pete Seeger: A Time to Sing

“He passed away, that doesn’t mean he’s gone.” Arlo Guthrie

Sometimes it seems life spins us through a series of circles and cycles. Along the way we find the wise ones; heroes we call them. Our cultural heroes sit uncomfortably on a pedestal we make for them. When we have the opportunity to get to know them, the once famous legends in our eyes, become human with strengths and flaws like the rest of us. Of course, that’s because they are the ‘rest of us.’ This has never rang as true and as clear as in the life and legacy of Pete Seeger.

In the case of multi-instrumentalist, Matt Cartsonis who maintained a 30 year friendship with Pete Seeger, the circle became complete on January 27th when the man who was once his hero, then his mentor and finally his friend, quietly died at the seasoned and content old age of 94.

During an afternoon Pasadena coffee house meeting with Cartsonis just two days after Seeger’s passing, he generously shared his lifelong impressions with me of the man who did more than anyone else to shape his life. With a bittersweet smile that often reflected through his own grief, Cartsonis said, “I just can’t conceive of the world without Pete Seeger. No one could have done what Pete did.”

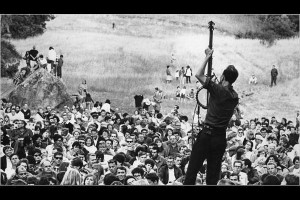

His life was marked by his love for diversity in all its forms and his refusal to judge others, even those who considered themselves his bitterest enemies. He lived and embraced the full spectrum of life. With Woody Guthrie (and at Woody’s urging) Pete hopped freight trains. He reached out to anyone who would listen, not to share with them ideology or political propaganda, but to spread the pure joy of the song. He went to labor camps, hobo jungles, union hall meetings, elementary schools, universities, state capitols, rescue missions, churches and hospitals. In 2009, he stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and sang all of the verses to “This Land Is Your Land,” uncensored, with lyrics that would inspire while they pointed to the ironic and needless absurdity of the plight of the poor against a political system rigged in favor of the wealthy. Ironically, it was on the inauguration day of our first African-American president. For many of us, one of the last photographs of him we saw was singing with the protesters at Occupy Wall Street in New York City.

In the most polarized, divisive and controversial of times, the McCarthy era, when artists were fearful for their careers and freedom, Pete stood up for free-speech by refusing to name his friends with communist associations or to disavow his own political leanings. He offered instead to sing for the House of Un-American Activities Committee the songs he loved best as a way of demonstrating his views and his patriotism. When he was blacklisted from every available venue a folk singer could possibly perform, he took his songs and stories to schools and played his music for children and college students in universities throughout the United States. This was one of the major currents that, a few years later, would give birth to the folk music renewal of the late-50’s, which would collide with the Civil Rights Movement. Those who supported the actions of HUAC thought they had heard the last of Pete Seeger in 1950, but a little over a decade later“Where Have All The Flowers Gone,” hit the national charts courtesy of The Kingston Trio and a new generation of young people were singing songs like “We Shall Overcome,” and the electrified Byrds version of “Turn, Turn, Turn.” While the actions of HUAC are remembered today as divisive, fearful hate mongering, these songs are among our most beloved treasures.

Seeger continued to sing and eventually, with the help of successful folk & country based entertainers who found success in television like the Smothers Brothers and Johnny Cash, the back of the dated blacklist was fatally broken over ten years after Joe McCarthy himself had succumbed to alcoholism and an early death, eaten up by his own hatred. Pete was victorious with a minimum of judgement, and with inclusiveness, courage, generosity and compassion. Pete Seeger was that rare activist with a sense of humor and a genuine love for even those who differed from his beliefs. He refused to believe the worst of anyone. In a recent interview with Time magazine, folksinger, Arlo Guthrie said, “A lot of people ascribe political reasons to his becoming involved in different causes, but they were bigger than that. They were not an ideology; they were part of his soul, and part of the American soul.”

He also grew up hearing Seeger’s music and like many folk music loving baby-boomers, Seeger was an established fact in the fabric of his life.

It was a correspondence about steel drums, that would give Cartsonis the opportunity to join Seeger at his home in the 80’s

“I wrote him a letter when I was working with troubled kids in Key West, “Cartsonis recalls. “He introduced me to the steel drum through a book he had written in the late-50′s.” He explained. “I wrote him a letter. Pete had said it was his biggest headache that he’d get mail and couldn’t answer all of them. I didn’t expect a response. He wrote me back! I nearly soiled my trousers!” he laughs.

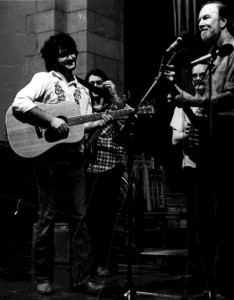

“When I showed up at the Clearwater Annual Meeting, my friend, Geoff Brown said he’d introduce me to ‘Pops.’ The first thing Pete said to me was, “‘Do you play banjo?’ He handed me the banjo and with Geoff on harmonica we played for an hour.” He Remembered. “After that, I joined the Beacon Sloop Club, a grassroots community activist group. The headquarters was in an abandoned boxcar. It was part of Pete’s vision to take on causes up and down the river.” Cartsonis explained. “We used to back up Pete for benefits. He started calling Geoff, Norman Plankey, Kim Seeger and myself the Garbage Pickers.”

Cartsonis continued to visit Pete for summers from 1980 until 1984. He explained, “Being that close to Pete and Toshi (Pete’s wife), are the greatest memories ever.” One common impression that others have had of Pete and Toshi was reinforced by Cartsonis: “Pete and Toshi were not separate. There would be no Pete without Toshi. She was not the woman behind the man. They were a unit. They talked the talk, literally. They did so fucking much. It was unbelievable. They were two of the most powerful people I ever met,” he says.

Even so, according to Cartsonis, Pete had his weak moments as well. “One year, I just showed up unannounced at Pete’s door. Toshi was not there. “I knocked on the door and Pete comes up in his gym shorts and t-shirt. He said he was so depressed.” He said, ‘I feel like I haven’t done anything. What’s it worth? There’s just a generation of couch lizards out there. What is it all for?’ Cartsonis continued, “I thought about a hundred different ways to rebut his feelings. I thought of the thousands of people he influenced. I guess even someone like Pete can be prone to being discouraged at times.”

When asked about conversations with Pete about the HUAC and McCarthy era Cartsonis said, “He never talked about it. It wasn’t something any of us thought about.” Cartsonis continues, “I was lucky and honored to know Pete and Toshi. They were walking, living, breathing life-lessons.”

But knowing Pete and the depth of his integrity became transformational when he realized the key to Pete’s life was, more than anything else, about reaching out to the world around him.

“I was a musician who could spend a lot time sitting alone in a room. It made me feel good. But, Pete knew integration. He

“But, that came with responsibility, “he adds. “Pete’s responsibility was to the political, ethical, environmental. He was the same inside and out. He was extremely open. He was the same with everybody. He was a commie in that way. He treated everyone the same.”

As we concluded, a light seemed to ignite in Cartsonis’ eyes. “You know I said that no one could do what Pete did?” He continued, “Knowing him has given me something to live up to. Being his friend comes with a moral imperative toward action. We have to fill that gap now. I said no one can do what Pete did, but now we can and we need to do it…to take positive action in our world.”

Then, with a smile that rested on the brink of a tear, he said, “Pete Seeger was more American than anyone I can think of…..”

So, today, somewhere outside of the time we live in, Pete Seeger, the man who was so engaged in his life, is perhaps sailing down that golden river he once sang about. To say this is the end of an era would be wrong. After talking with Matt Cartsonis, it is now clear, the era of Pete Seeger has just begun and if we want to see where it resides, we have only look into each other’s eyes.

There will be a tribute to Pete Seeger at The Coffee Gallery Backstage in Altadena, California on March 9th at 6:00 PM. Matt will be performing with John York, Carla Olson, Ross Altman and Susie Glaze.

This article was originally published in Turnstyled Junkpiled