Roland White: Then and Now, A Mandolin Mentor

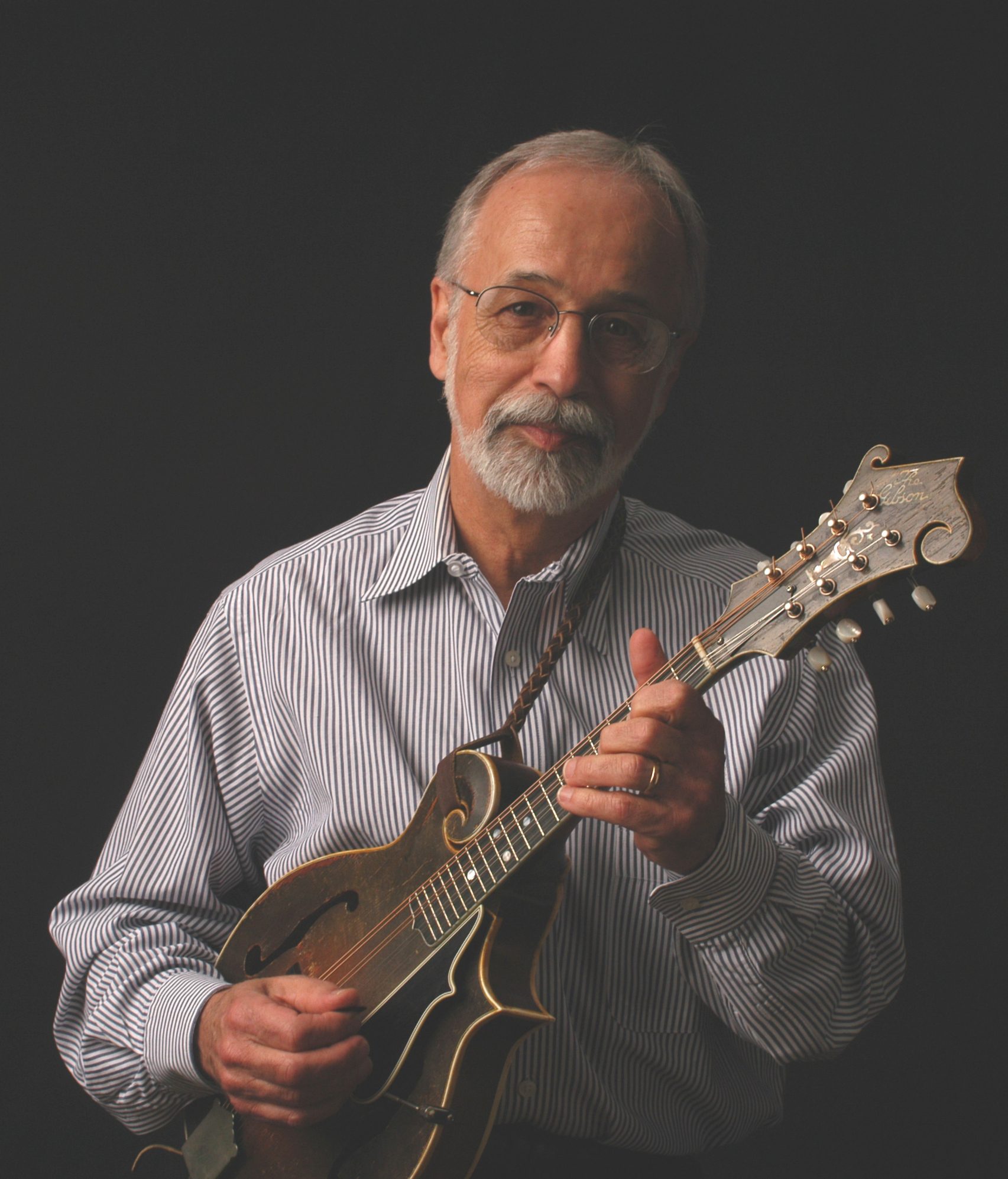

Photo by Mickey Dobo

Since he began performing more than six decades ago, Roland White has left his mark on bluegrass music with his singing, guitar playing, and particularly his mandolin playing, which has been inspiring to multiple generations of musicians. His discography reveals both his consistent musicality as well as his development from a young virtuoso into a confident master of the mandolin over the course of a truly amazing career. His style, defined by his groove, cleverness, drive, whimsy, and mastery of phrasing, is both familiar and singular in a way that has carried the bluegrass tradition forward.

White grew up in a musical family from northern Maine. By the time the family moved to Burbank, California, in 1955, he and his siblings were performing informally in various configurations, and three of the brothers, including Roland, started performing regularly in 1957 as The Country Boys. Originally playing a broader range of folk and fiddle tunes, they didn’t play bluegrass until Roland, the oldest brother and leader, heard a recording of Bill Monroe. Having never heard anyone play so fast, Roland and the band, which had expanded to include some non-family members, started practicing. Though White admits that he could never imitate what Monroe was doing, he immersed himself in the style and attempted to recreate the energy of Monroe’s music.

The Country Boys were a fixture in the Los Angeles music scene, appearing on studio sessions, in movies, and even on The Andy Griffith Show. White had been drafted and didn’t appear on their first album, The New Sound of Bluegrass America, but the album, released in 1963 under their new name, The Kentucky Colonels, did feature the lead guitar playing of Roland’s younger brother, flatpick guitar innovator Clarence White. The Kentucky Colonels’ second album, Appalachian Swing, has been described as one of the most exciting bluegrass albums of the 1960s. Roland and Clarence’s incredible talents are shown on tunes such as “Barefoot Nellie” and the “John Henry Blues” (both can be heard on Flatpick, a compilation of recordings from Clarence White). Roland’s solos feature long streams of lightning-fast notes and dissonant accents, clearly influenced by Bill Monroe but with a style of his own.

While The Kentucky Colonels released only two full-length studio records, many albums of their live recordings are now available. Among them are recordings from their 1964 East Coast tour (Long Journey Home), including performances at Club 47 in Boston and at the Newport Folk Festival, an appearance that launched the Colonels to legendary status in the bluegrass community before they disbanded the following year for financial reasons.

Roland soon found himself on a new course after he was asked to fill in for Bill Monroe’s band, who were trapped in Texas on their broken-down bus. Monroe had a week-long residency at the Ash Grove, a legendary L.A. folk club, and he had flown to L.A. to play the shows while the band stayed behind to repair the bus. At the end of the residency, Monroe asked White to stay and finish the tour, but then learned that his guitarist was going to resign. White, who didn’t play much guitar at the time, auditioned, got the job, and moved to Nashville, playing with Monroe for nearly three years.

Monroe was known to be demanding of his backup musicians, and White learned a lot about the galloping rhythm of bluegrass from his time with Monroe. White played guitar and sang lead on some of Monroe’s most famous recordings of that era, including “The Gold Rush” and “Walls of Time” (available on Bill Monroe – Bluegrass 1959-1969). This time changed White’s stylistic and physical approach to the mandolin. Monroe suggested that holding the pick in a particular way would give the music a certain rhythm. White worked hard to incorporate this new right-hand technique to improve his mandolin playing.

White resigned from the Blue Grass Boys to find more frequent, lucrative work around the same time that musical differences split up Flatt and Scruggs. In 1969, White became one of the original members of Lester Flatt’s new band, The Nashville Grass.

White’s new pick grip and his time with Monroe brought a steadier rhythm, a deeper tone, and a more concise approach to soloing that are audible on his recordings with Flatt. His solo on “When You Are Lonely” (on Flatt and Mac Wiseman’s On the South Bound) is more melodically straightforward than a lot of his previous playing but utilizes more double stops to remain dynamic and expressive. This style carried into his next project, which would once again be with his brother Clarence.

In 1973, Roland and Clarence toured as The White Brothers, producing some live recordings that have since been released on CD. Their shows in Holland and Sweden feature two much more musically mature but still energetic bothers. Roland shows much more control on songs like “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome,” playing with a much steadier tremolo and better tone than in his earlier recordings with the Kentucky Colonels. These recordings also show the development of Roland’s harmonic mastery. Throughout the rest of his career, his use and composition of double and triple stops, like on his kickoff to “Good Woman’s Love,” add an unmistakable layer to his style.

Unfortunately, this musical venture was suddenly cut short later that same year when Clarence was killed in a car accident. Roland was injured in the accident but recovered and was approached by The Country Gazette to play guitar. The Country Gazette had been formed by fiddle player Byron Berline, essentially as the bluegrass portion of the Flying Burrito Brothers’ show. The sudden death of Clarence, and Gram Parsons shortly after, caused an abrupt end to the momentum of the Southern California country rock scene. The Country Gazette still planned to tour, though, and although Tony Rice auditioned, he didn’t get the job because he couldn’t sing tenor.

For 15 years The Country Gazette put out some of the most creative, technically proficient music ever played on banjos and mandolins. In addition to their undeniable virtuosity, The Country Gazette’s music had a sense of whimsy, due in no small part to the senses of humor of White and banjo innovator Alan Munde, that made it both compelling and accessible. But the novelty of songs like “The Great Joe Bob” (American and Clean) and covers like Elton John’s “Honky Cat” (Don’t Give Up Your Day Job), while highly entertaining and impressive themselves, may have overshadowed the beauty, brilliance, and technical ability of songs like “Stop Me” (America’s Bluegrass Band) or “Charlotte Breakdown” (America’s Bluegrass Band).

White’s playing shines in this era. The Country Gazette’s recordings of classic bluegrass songs such as “Molly and Tenbrooks” or “Kentucky Waltz” (Hello Operator … This Is Country Gazette) exhibit the coalescence of White’s energy and inventiveness with his rhythmic and stylistic advances made while playing with Monroe and Flatt. His masterfully controlled but not overworked tremolo, played with beautiful tone and placed perfectly before, after, or on the beat, is definitive of White’s style. In addition to his technical skills, his sense of music and beauty are clearly evident in songs like “Drowning the Flame of Love” (American and Clean).

White stopped playing with the Gazette and joined the Nashville Bluegrass Band in 1989. The Nashville Bluegrass Band was one of the most important bands of the new golden age of bluegrass, incorporating black gospel elements into their otherwise driving bluegrass sound. Like the Country Gazette, the Nashville Bluegrass Band featured some of the greatest musicians of the time, including legendary fiddler Stuart Duncan. White brought some of his swingier playing from the Gazette into this band with songs like “I’ll Just Keep on Lovin’ You” (Home of the Blues), but he was no stranger to the blues. His solos on songs like “Rock Bottom Blues” (The Boys Are Back in Town) bring out a more experienced, updated version of his earlier Monroe-influenced sound.

The Nashville Bluegrass Band garnered four Grammy award nominations, including two wins during White’s time with them before he moved on to start his own band, The Roland White Band, in 2002. The first CD they recorded, Jelly on my Tofu, was also nominated for a Grammy. In 2017, White was inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame.

The Next Generation

Roland White was one of my first musical influences. Before I even met him, my mandolin teacher bought me a copy of Roland White’s Approach to Bluegrass Mandolin,which I learned a lot of my first tunes from. That same teacher had him write me a very encouraging note, which I framed and hung on my wall to motivate me while I practiced.

I finally met Roland when I was about 13 and accompanied my dad, Jeff Scroggins, to Kaufman Kamp, a weeklong bluegrass workshop where they were both teaching. His gentle nature and clear mastery of bluegrass was easy to learn from, and he was particularly encouraging to all of the young players in the class. He gave us room to show off while also gently making suggestions about how to improve our playing.

I didn’t know much about the White brothers or the Colonels while I was growing up. I was, however, familiar with some of the tunes they recorded. “Soldier’s Joy” was one of the first tunes that Roland ever learned and, incidentally, became one of the first tunes I ever learned thanks to his instructional book. I played his version of this tune in my fifth-grade talent show.

My dad learned how to play banjo from Alan Munde, so his style and the music of The Country Gazette were very prevalent in my youth. Alan innovated melodic banjo playing and had a truly remarkable sense of how to interpret sung melodies on an instrument — a sense he passed on both to my dad and, to some extent, Roland. I remember watching a YouTube video of them performing “Saro Jane” and noticing Roland making a face after his solo as if he messed up, but I have never been able to figure out what went wrong.

The Nashville Bluegrass Band and its members are a huge influence on me and others in my generation. When I joined my first local band, they gave me a flash drive with a bunch of bluegrass on it and I listened to “Rock Bottom Blues” over and over. The first solo I learned by ear was the kick-off to The Dreadful Snakes’ version of “Who’s that Knocking at My Door,” which featured Roland and fellow NBB member Pat Enright.

On the Scene

White has led such an eventful and significant life that it’s difficult to write about it comprehensively. In addition to his vast musical résumé, only some of which is covered here, he’s also been an active and important member of the bluegrass community and a mentor for many younger musicians. That work — as well as his musical accomplishments — continues to grow.

Last year, White released a tribute record to The Kentucky Colonels. In addition to many of the usual Roland White Band members, the recording features several of bluegrass’ most exciting young musicians following in the footsteps of White and his brothers, including Molly Tuttle, Brittany Haas, Kimber Ludiker, Justin Hiltner, Gina Clowes, Russ Carson, Patrick McAvinue, and many others. At 80, White’s control of phrasing and melody continue to shine.

I’ve gotten to see Roland in person a lot more since I moved to Nashville last year. He is ubiquitous at the Station Inn, either watching people’s shows or putting on events of his own. Just like when I met him at Kamp, he has always been extremely encouraging to me and other young musicians. My first gig after I moved to town was his Bill Monroe Appreciation Night at the Station, where I played with many other young musicians I look up to, such as Casey Campbell and Tyler Andal. When the Roland White Band plays at the Station, Roland will invariably spot younger musicians in the audience and get them up to play with the band. One time, Roland had me and Casey Campbell, two fellow mandolin players, sit in for the entire second set. And once, when I didn’t have my mandolin with me, Roland gave me his to play for a few songs while he sang.

Roland White is a role model both as a musician and as a leader. His commitment to the future of bluegrass seems endless, and while his style remains singular, his influence can be seen in the countless hours of kindness and mentorship he has given to multiple generations of musicians.

* * *

To accompany this piece, I’ve compiled a chronologically organized Spotify playlist that features nearly all of the songs that I’ve mentioned, as well as a few others, to show a glimpse of the great music Roland White has made. (It’s actually part of a much larger playlist if you find yourself wanting more.)