ROOTS IN THE ARCHIVE: Test Pressings Help Keep Robert Johnson’s Songs Alive

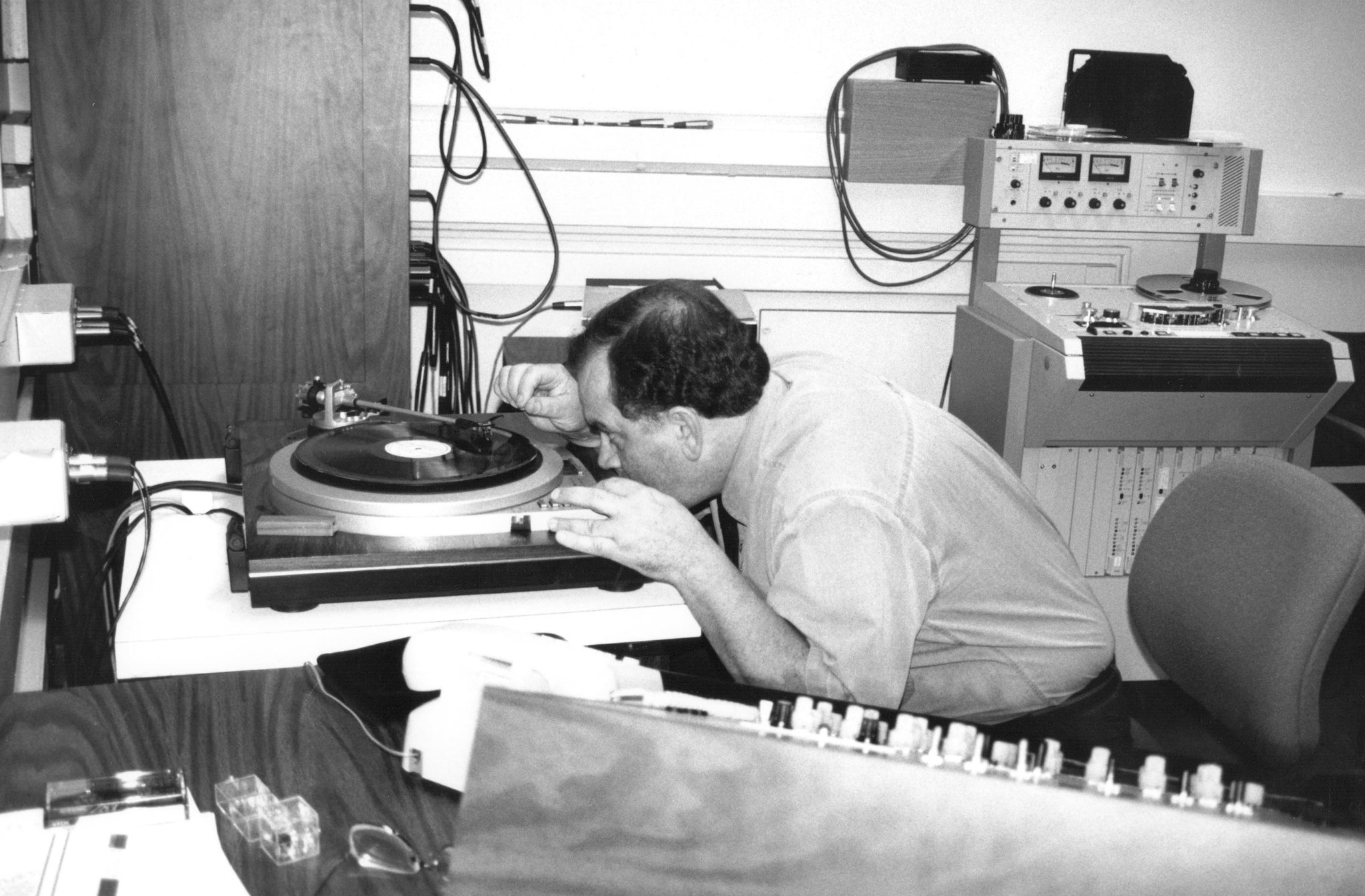

Senior Audio Production Specialist Michael Donaldson in the recording laboratory of the Library of Congress in 1997. Donaldson was making a transfer of the Robert Johnson test pressing of “Traveling Riverside Blues.” (Photo by James Hardin, Library of Congress)

No American roots musician is the subject of more myth, mystery, discussion, and debunking than bluesman Robert Johnson. Some still whisper that he learned his powerful playing technique through a deal with the devil — even though this is a venerable legend told of many musicians before Johnson was even born, and even though the story was never attached to Johnson until years after he was dead. Most blues historians subscribe to the less fanciful idea that Johnson learned to play through talent and hard work, over several years spent playing and in some cases wandering the country with Johnny Shines, Honeyboy Edwards, Henry Townsend, and other peers. What no one disputes is that, although he died at only 27 years old, the 42 recordings Johnson made are foundational to American blues music. For one of those takes, no master exists, and the only pressing known to have been made resides in the American Folklife Center archive at the Library of Congress. It’s just one of more than 30 Robert Johnson test pressings acquired by the AFC archive over the years.

The discs, known in the record business as “test pressings,” were part and parcel of record company operations in the days before tape recordings. After a master recording was cut direct to disc on a recording turntable, it would be sent to the record company’s factory, where metal copies were made and used to stamp shellac discs for commercial release. Occasionally, in addition to the mass production of the record, a company stamped a copy for internal use by staff, and these are the discs known as test pressings. In many cases, these copies were played only once, or not at all. In some cases, the only extant copy of a recording is such a test pressing; and in many cases, the clearest extant copy is. Since record companies abandoned older stamping equipment years ago, even where the metal plates exist it is almost impossible for new, playable pressings to be made from them. For this reason, a test pressing of a commercial 78 rpm is always a rare item.

Coming into its own in the early 20th century, the commercial 78 represented an important development in the history of the interplay between traditional and commercial music. Because there were national, regional, and ethnic markets developing for recorded music in the first three decades of the century, commercial record companies often recorded traditional music, including blues, folk ballads, old-time string bands, Cajun music, and other ethnic and regional genres. So in these years record company officials sometimes acted like folklorists, traveling around the country with recording equipment collecting traditional and roots music. Robert Johnson was recorded in this way by producer Don Law for Arc/Brunswick, which later became Columbia Records. Their first sessions took place in a hotel room at the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio, Texas, in 1936. Another set was done in a makeshift studio in the company’s branch office in Dallas in 1937. During these sessions, Johnson recorded 42 disc sides representing main and alternate takes of 29 unique songs. About 18 months after the second session, Johnson died, probably as the result of poison given to him by the husband of a woman he was flirting with.

Johnson was known to a small circle of enthusiasts during his lifetime, but his reputation as a blues innovator, and his status as a major inspiration for many other musicians, flourished mainly after his death. One person who was intrigued by Johnson’s music even in the late 1930s was Library of Congress folklorist Alan Lomax. During his 1941 field trip to the Mississippi Delta, Lomax looked for Johnson, only to discover the bluesman had been dead for over two years. Son House helped Lomax track down Johnson’s mother, and the folklorist took a few notes about their visit, which still remain in the archive, but tragically, he was too late to record Johnson. In the mid 1940s, though, Lomax and George Avakian produced a series of blues and jazz reissues, and Columbia made Lomax six text pressings of Robert Johnson at that time, which remained in his possession until the Library of Congress bought them in 1997.

Johnson’s fame grew drastically in the 1960s, based mainly on the 1961 Columbia LP King of the Delta Blues Singers, a compilation of Johnson’s best sides. Suddenly, Johnson’s music was available to whole new generation of musicians. People like The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and Eric Clapton were singing Johnson’s praises, and he came to be regarded as one of the all-time greats of American music, even outside his home territory in the Mississippi Delta.

King of the Delta Blues Singers was produced by Frank Driggs, who also worked on many other reissue projects for Columbia. In order to do this work, Driggs needed test pressings, which Columbia duly made for him. Much of Driggs’ collection, including the test pressings and related manuscripts, ended up in the private collection of blues enthusiast and researcher Tom Jacobson. The Library of Congress acquired this collection in 2005, and Driggs’ test pressings joined Lomax’s in the American Folklife Center archive.

Lomax’s test pressings include “Rambling on my Mind,” “Drunken Hearted Blues,” “Stop Breakin’ Down Blues,” “Love in Vain,” “Milkcow’s Calf Blues,” and “Traveling Riverside Blues.” The Jacobson collection includes 25 test pressings of 11 Robert Johnson songs: “Rambling on My Mind,” “When You Got a Good Friend” (takes 1 and 2), “Phonograph Blues” (takes 1 and 2), “32-20 Blues,” “If I had Possession Over Judgment Day,” “Little Queen of Spades,” “Drunken Hearted Man,” “Me and the Devil Blues,” “Stop Breakin’ Down Blues,” “Love in Vain,” and “Milkcow’s Calf Blues.”

Although all of these songs, in all their recorded versions, have been reissued on CDs, these test pressings are still a crucial piece of the Robert Johnson story. In fact one of the Lomax pressings, an unissued take of “Traveling Riverside Blues,” is unique as far as we know; it was not even known to exist by Columbia until after the Robert Johnson compilation The Complete Recordings came out as a two-CD set in 1990. The alternate take of “Traveling Riverside Blues” is therefore the only known recording of Johnson that is not on that set.

When the Library of Congress bought the test pressing in 1997, the publicity alerted Columbia to the take’s existence, and the Library of Congress made them a copy. Columbia issued it as a bonus track on the 1998 CD reissue of King of the Delta Blues Singers, and it later appeared on the 2011 remastered set The Centennial Collection/The Complete Recordings, finally taking its place among Johnson’s complete works.

The American Folklife Center’s test pressings acquired from Jacobson have also been issued on CD. Considering them the best known copies of Johnson’s music, and calling them “astonishing mint test pressings,” the Pristine Classical label used them as the basis for its 2016 Robert Johnson compilation, Phonograph Blues. The label has placed one track online, “When You Got a Good Friend”:

In addition to test pressings, the Jacobson collection includes correspondence between Frank Driggs and Don Law, the reissue producer and the original producer/engineer. One document, which takes the form of typewritten questions from Driggs and handwritten answers from Law, includes Law’s important first-person account of the recording sessions. Law’s description of Johnson, who died less than two years after their final session together, is terse and poignant: “Medium height, wiry, slender, nice looking boy. Beautiful hands.” The collection also includes other Columbia Records documents relating to Johnson. It features correspondence with the late blues researcher Mack McCormick, who claimed to have discovered the identity of Johnson’s murderer and to have obtained a confession, but who died without publicly revealing the man’s name.

Through these test pressings and other materials, the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress has a valuable treasury of Robert Johnson’s music and related information. Even though Johnson never recorded for Library of Congress fieldworkers, the Library’s American Folklife Center is still a necessary stop for anyone trying to piece together the complete story of one of the greatest and most mysterious figures in the blues.

Stephen Winick is a writer and editor for the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress and editor of their blog, Folklife Today. Because the Library of Congress is federally funded, these columns are in the public domain, not subject to No Depression‘s copyright.