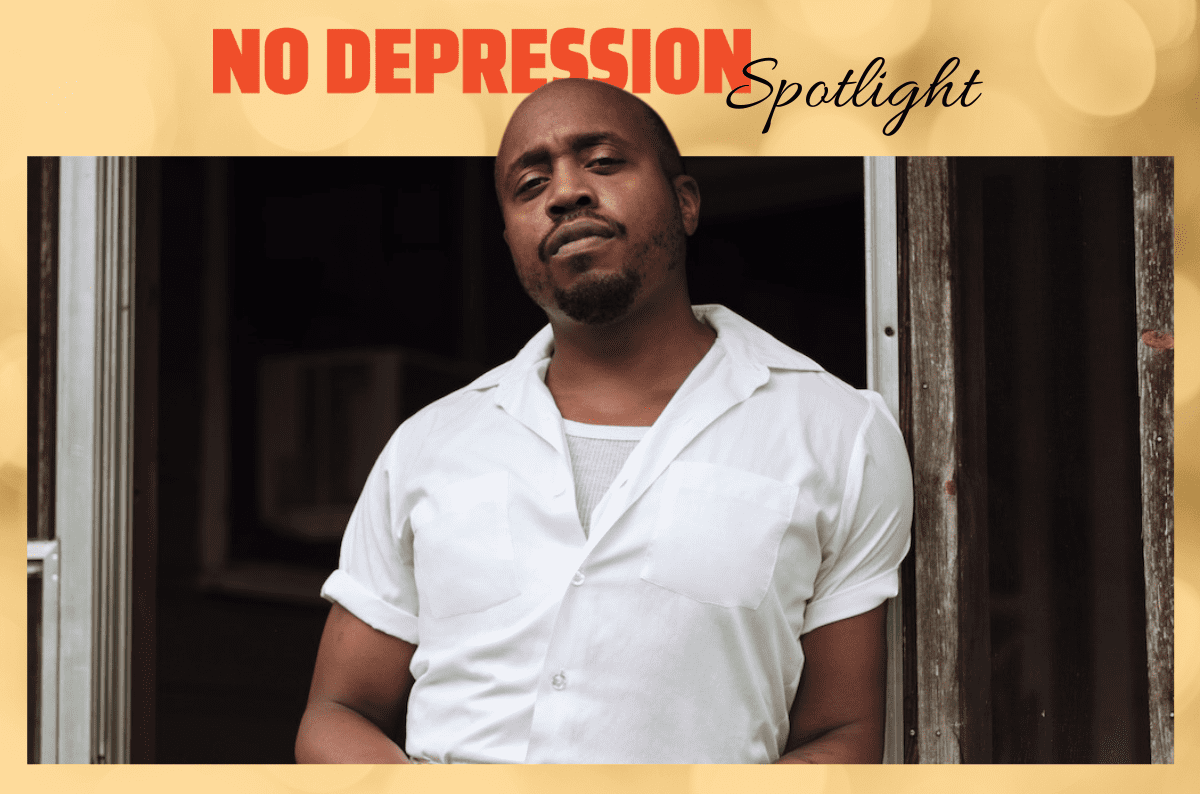

SPOTLIGHT: Durand Jones Hits Home with ‘Wait Til I Get Over’

Photo by Rahim Fortune

EDITOR’S NOTE: Durand Jones is No Depression’s Spotlight artist for May 2023. Look for more about him and his new album, Wait Til I Get Over, out May 5 on Dead Oceans, all month long.

If you thought you knew Durand Jones as an artist, think again.

For the past decade, the singer has carved out a role as co-lead singer of soul/R&B outfit Durand Jones and the Indications, serving as the rougher-hewn vocal counterpart to the saccharine falsetto of drummer Aaron Frazer. While Jones is fantastic in that capacity, he’s ready to show the world the full range of his skills and creativity on his solo debut.

Jones is releasing Wait Til I Get Over on May 5 via his and the Indications’ longtime label Dead Oceans. It’s an album that in terms of writing and recording is the culmination of nearly 10 years of thought and work. From an existential standpoint, it’s been a lifetime in the making.

“With doing a solo project, I wanted to try things I always wanted to, but never had the opportunity to do,” says Jones. “I knew that with this record I wanted to personally tell a story that was reflective of my own musical journey and express it in a way that’s not a cliché, but is cohesive.

“Honestly, all my life experiences ultimately led me to this moment. Each song, in one way or the other, really tackles a point in my life. I wanted to use the record in a way that could peel back the issues and traumas within myself that were weighing me down. Now that I’ve released them, I feel free.”

Getting It Right

The fulcrum on which Wait Til I Get Over pivots is defined by the album’s second track, a spoken word interlude titled “The Place You’d Most Want to Live.” Jones says:

“If you follow the Mississippi River as she swivels and turns tightly — unable to move freely because of the levy, you’ll find Hillaryville. A small place in Louisiana’s Atchafalaya basin. This place was founded by eight slaves who received it as a form of reparations after the American Civil War. Most visitors are still greeted by the tall, sprite green, green sugar cane basking in the presence of the sun. When asking my Gran ‘What was it like’ when she first moved to Hillaryville, her reply was always the same:

“The place you’d most want to live.”

Gran’s Hillaryville was much different than that of Jones’ childhood and the present day. Growing up, he experienced the community’s change from rural, Black Southern idyll to a place where history and tradition were falling to the wayside.

“Lord Have Mercy” is the visceral lead single on Wait Til I Get Over. Recorded in the studio with a live band, it’s an explosive blues-gospel hybrid that immediately follows “The Place You’d Most Want to Live” and serves as a way to contrast the varying generational experiences of living in the town.

“‘Lord Have Mercy’ is raw, raucous,” Jones explains. “I really wanted to lean in on the hardness of my vocals to highlight the difference between her generation and what it became: a place you wanted to escape. Oftentimes when I go home now, dudes tell me, ‘Yo, n—-, you got out!’ And I hate that so much.”

While he can reconcile the changes to Hillaryville now, that discrepancy was hard to live through as a kid.

“Growing up in Hillaryville, it was in a way tranquil and in other ways really raw. I love to call it ‘country ’hood,’” he says. “You’d see a Cadillac with 20-inch speakers blasting Master P, then you’d see someone riding down the road on a horse. I felt like I really got to see the elders, my grandma’s generation and the traditions they held being met with new traditions: technology, hip-hop. Being in the middle of that made me so anxious. I felt like seeing that, just the way the old and new go up against each other like that, made me want to leave even more.

“It took leaving to find myself. When I came back after leaving, I was more assured of myself,” Jones notes.

Leaving Hillaryville for college at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana, allowed for two things to happen. First, he met his Indications bandmates. Just as importantly, it gave him the necessary space to think about Hillaryville and its historical and personal significance.

There aren’t many places in America with the backstory of Hillaryville and its status as a form of reparations. It made Jones think about its trajectory since its inception and how it went from a flourishing agricultural community to a struggling small town.

“I think Hillaryville’s legacy is living through the context of the place. It was given to eight formerly enslaved men as reparations after the Civil War; you rarely hear cases about (Black people) receiving reparations,” Jones says. “The first thing they did was create a community, built a school, church, restaurant, general store. It became self-sustaining.

“Most of the sugar cane is gone now, and there’s subdivisions. People don’t know the history and legacy of Hillaryville, or see it as a nuisance and want to wipe it down and put a development on top,” he continues. “Things changed so much in the community and I wanted to reflect that through the record by telling the story of Hillaryville and telling my story about how it made me who I am. My duty, part of my legacy, is to shed light on this place and show that America got it right with these eight men.”

Points of Reference

Finding the right opportunity to tell those stories took some time. In 2015, Jones and the Indications were picked up by Colemine Records, and they hooked up with Dead Oceans a couple years after that. Between 2016 and 2021, the group released three well-received records, with the latter two (American Love Song and Private Space) cracking the top 20 on the Billboard Indie chart and top five on the Heat chart.

That type of upward career arc and the group dynamic put Jones’ passion project on the backburner. Despite that, the ideas continued to percolate.

“The reason I waited, kept it in my back pocket, was that I was in deep with the Indications. We made three records, and I didn’t have the time and space to tell my own story,” he says. “At the time, I wasn’t necessarily writing with the purpose of creating a record. We tried a couple of the songs with the Indications but they didn’t really work. But the songs were building up and building up, so when the time came, I didn’t have to start from scratch.”

After the release of Private Space in July 2021 and its ensuing tour, the members of the Indications got to work on their own individual projects. Drummer Aaron Frazer commenced activity on a second solo album, which should be released this year, and keyboard player Steve Okonski released a Frazer-produced jazz record titled Magnolia in February.

Jones, who now lives in San Antonio, was able to pursue what became Wait Til I Get Over. The song ideas came together fast, and he used this time to mix it up a bit and pursue an eclectic sonic palette that touched on the full range of his musical tastes and college studies in classical music.

“Honestly, all of the songs really came easily. I feel like they found me in some ways,” he says. “Because it’s so personal and everything came from experience and was so fresh and raw at the time, I was in a good place to be creative and workshop.

“It was really varied for me, a lot of going to the piano, hearing chords, and figuring out what fit with them,” Jones continues. “Otis Redding, The Beatles, Wilson Pickett, Donny Hathaway were really influential.”

But his biggest creative influences weren’t musical at all. Jones drew inspiration from literature, namely Sula by Toni Morrison, Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward, and Just Above My Head by James Baldwin. These novels trace the history of relationships and community and, in the case of the Baldwin novel, focus on queer identity, ideas that are crucial components in Wait Til I Get Over.

In the studio, Jones drew on other non-musical reference points, from photos of Hillaryville that he and photographer Rahim Fortune worked together on to artwork he found moving. The goal was to stoke his and his band’s creativity.

“Once I was given a chance to create this record, I revisited all those novels and writers. They were really influential because I wanted this to be a musical novel, my musical memoir,” he says. “Even more in the studio, working with [album co-producer] Drake Ritter, we drew on other influences. I held up a picture of this painting by Anna Buckner and said, ‘I want a groove as amorphous, as cool as this painting is.’

“It got super abstract. Not too many musicians are into hearing weird-ass shit like, ‘That was too purple, I need more red,’” Jones adds with a laugh.

Unpacking and Elevating

There’s a lyric in the album’s title track where Jones sings, “Wait ’til I get over, I’m gonna lay my burdens down.” It’s an apt metaphor for the emotional release he felt in completing the record.

“‘Burdens’ is a perfect word; there was a big feeling of letting these emotions wash away and lifting myself free of them,” he says. “It was a therapeutic process where I was able to unpack so much trauma, there was this sense of elevation from having never been this vulnerable before and finding strength.”

That vulnerability is most heartrendingly expressed by the song “That Feeling.” The ballad is a first for Jones. He’s written and sang love songs before, but never ones about himself, about one of his relationships and his identity as a queer man.

“Whenever I write love songs, I try to be as ambiguous as possible because I want people to feel comfortable singing along. So many songs I love, I could tell they weren’t intended for me to sing,” he says. “But with this being so personal, I needed to not be ambiguous and be straightforward.

“I wanted to highlight important love stories in my life — ‘Gerri Marie,’ ‘Sadie’ — I needed to put ‘That Feeling’ on the record.”

Now that Wait Til I Get Over is out in the world, Jones is touring behind it with the Bloomington-based musicians who played on it. He warns listeners “don’t expect an Indications show,” but to be ready for one helluva time.

“I want to blow their minds, like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. I want riots in the streets,” he says lightheartedly.

He’s also looking ahead to his next solo endeavor. Jones says he would like to explore classical and jazz composition and further “encapsulate who I am musically.”

Also on his mind is a proper sequel to Wait Til I Get Over. He doesn’t necessarily have anything written for it, but Jones understands what he wants it to sound like and what the overarching concept would be.

“I fit into my town because the town made me who I am, and I really tried to show that sonically,” he says. “I’ve been thinking about a part two because this record is the sense of longing for your home. The next one, I want to actually be home.

“I want to play with all my Louisiana friends that I haven’t played with in forever. I want it to feel like Louisiana.”