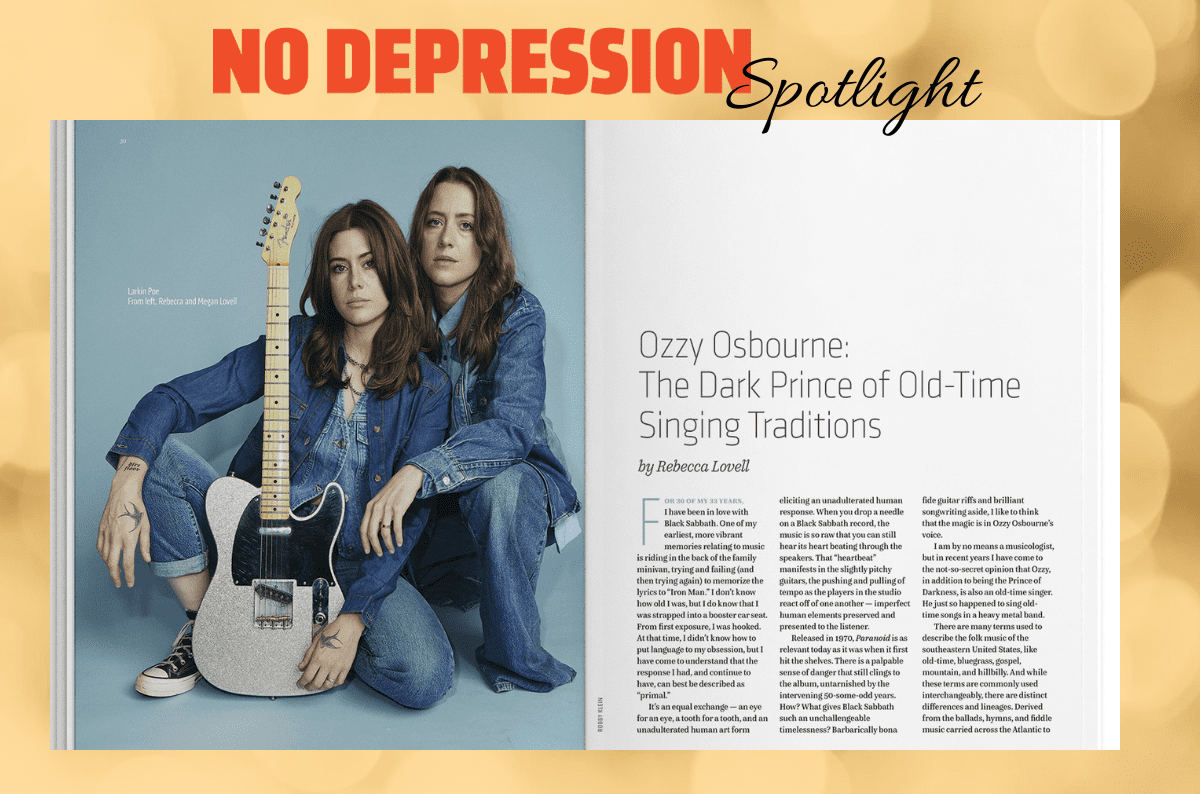

SPOTLIGHT: Larkin Poe on The Dark Prince of Old-Time Singing Traditions

EDITOR’S NOTE: Larkin Poe No Depression’s Spotlight artist for Jan. 2025. Learn more about them and their new album, Bloom (released Jan. 24 on Tricki-Woo Records), in this feature. This Spotlight essay is also special because it originally appeared in the Winter 2024 print issue, which is available here.

For 30 of my 33 years, I have been in love with Black Sabbath. One of my earliest, more vibrant memories relating to music is riding in the back of the family minivan, trying and failing (and then trying again) to memorize the lyrics to “Iron Man.” I don’t know how old I was, but I do know that I was strapped into a booster car seat. From first exposure, I was hooked. At that time, I didn’t know how to put language to my obsession, but I have come to understand that the response I had, and continue to have, can best be described as “primal.”

It’s an equal exchange — an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and an unadulterated human art form eliciting an unadulterated human response. When you drop a needle on a Black Sabbath record, the music is so raw that you can still hear its heart beating through the speakers. That “heartbeat” manifests in the slightly pitchy guitars, the pushing and pulling of tempo as the players in the studio react off of one another — imperfect human elements preserved and presented to the listener.

Released in 1970, Paranoid is as relevant today as it was when it first hit the shelves. There is a palpable sense of danger that still clings to the album, untarnished by the intervening 50-some-odd years. How? What gives Black Sabbath such an unchallengeable timelessness? Barbarically bona fide guitar riffs and brilliant songwriting aside, I like to think that the magic is in Ozzy Osbourne’s voice.

I am by no means a musicologist, but in recent years I have come to the not-so-secret opinion that Ozzy, in addition to being the Prince of Darkness, is also an old-time singer. He just so happened to sing old-time songs in a heavy metal band.

There are many terms used to describe the folk music of the southeastern United States, like old-time, bluegrass, gospel, mountain, and hillbilly. And while these terms are commonly used interchangeably, there are distinct differences and lineages. Derived from the ballads, hymns, and fiddle music carried across the Atlantic to a yet unformed America by settlers of predominantly English and Scotch-Irish descent, “Appalachian” music represents one of the oldest forms of North American traditional music. As settlers of the colonial and revolutionary periods put down their roots in the deep hollers and grassy balds of the Appalachian mountains, their music naturally began to evolve. Borrowing from the musical influences of traveling tent revivals and medicine shows, Appalachian music began to diverge from its native source, acquiring a uniquely American sound.

Often referred to as a “high, lonesome sound,” the voices of the Appalachian traditions are plaintive and unadorned; stark melodies are presented plainly, with little to no vibrato. Listen to “O Death” by Ralph Stanley, or “Am I Born to Die” by Doc Watson. Both songs are sung a cappella, featuring dark lyrics that ruminate on the fleeting nature of existence. Now listen to “War Pigs” by Black Sabbath. And then listen to “Planet Caravan,” also from Paranoid. If you mute the instruments on “Planet Caravan” and strip away the warbled vocal effect, it doesn’t take a far flight of fancy to hear the melodic similarities between all four songs. I think this can be attributed, in large part, to the specific tonal scales that inform the melodic construction of the majority of traditional folk music.

“Western” music (as differentiated from “Eastern” music) is built upon diatonic scales. Simply put, diatonic scales are seven notes arranged in a specific pattern. There are seven commonly used “modes,” or patterns of scales: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. When listening to traditional Western folk music, the Dorian and Mixolydian scales are used time and time again to create the sorta major / sorta minor, sorta harmonious / sorta dissonant melodies that we have come to identify with Appalachian music traditions. Black Sabbath utilizes these same scales, along with a heavy dose of blues-informed minor pentatonic scales, to create a sound that harkens back to wiser, older musical traditions.

These wiser, older traditions have been weaving the lyrical themes of spirituality, mortality, fantasy, and grim reality together for centuries. With an ear finely tuned to the occult, Appalachian songs slice into the themes of death, evil, and violence with a blade honed as sharp as that of any heavy metal band. Listen to “Pretty Polly,” “Omie Wise,” or “Tom Dooley” — three examples from the regrettably long list of mountain songs detailing the gruesome murders of women. These murder ballads, which typically feature unsettlingly upbeat music, will raise the hairs on the back of your neck. A primal response. An unadulterated human art eliciting an unadulterated human response.

Maybe Black Sabbath has nothing to do with Appalachian music. Or maybe, to play devil’s advocate (I’m sure Ozzy would approve), there is a tie that binds. For certain, there is the synchronicity of human derivation: a perpetual generational borrowing that connects those of the past to those of the future. The river of shared musical tradition is wide and deep, flowing from continent to continent, bleeding out of one lifetime and into the next. A shared lifeblood that, just maybe, pulses from the heart of Appalachia and straight into the veins of a Prince of Darkness. And what could be more metal than that?