When the Newport Folk Festival approached Black Opry founder Holly G last November about curating a set at the 2022 fest, her initial response was disbelief. At that point, her organization only had one live show — the first-ever Black Opry Revue at the Rockwood Music Hall in New York — under its belt.

“It felt like a very big deal, especially because we were new,” she says. “That was a lot of trust they had to put in me, based on very little information that they had about who I was and what I was doing.”

A lifelong fan of country music who did not feel safe going to country shows, Holly created Black Opry in April 2021, envisioning it as an online space to celebrate the music she loved and offer a refuge for like-minded fans. Almost immediately, her website began attracting the attention of artists from all corners of the country, Americana, and roots world, and Holly became determined to create real-world opportunities for artists who had been tokenized or outright excluded.

Last September, the Black Opry hosted invite-only gatherings at an Airbnb in East Nashville dubbed the “Black Opry Outlaw House” during last year’s AmericanaFest, and the ideas and camaraderie there led to the first Black Opry Revue in New York. Less than a year later, Black Opry has put on more than 30 live revues across the country, featuring dozens of artists, with as many more events scheduled through the end of the year and a spot on next year’s Cayamo roots music cruise.

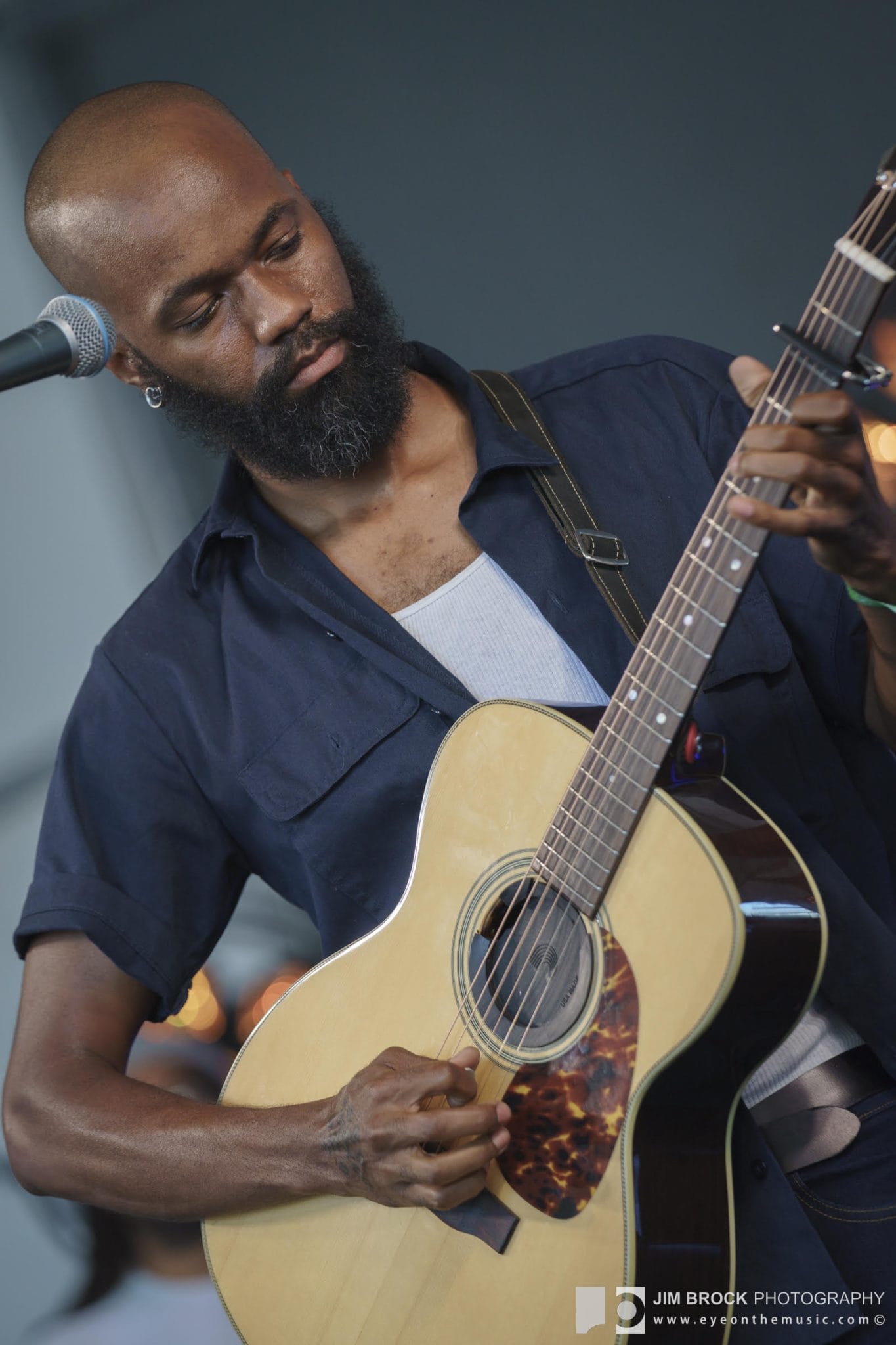

After agreeing to curate a set for Newport, Holly’s first move was to enlist the help of friend and mentor Rissi Palmer in putting together a roster of artists. They settled on a list of six — Autumn Nicholas, Julia Cannon, Chris Pierce, Lizzie No, Leon Timbo, and The Kentucky Gentlemen — with the addition of Joy Oladokun and Buffalo Nichols, who were already slated to play solo sets at the fest. Apart from a time limit of 60 minutes, slightly longer than the average set at the fest, the Black Opry was given complete creative control.

Next came time to find a backing band. Holly had recently met Ping Rose, a guitarist and bandleader whose trio had played with all manner of Nashville artists, at a Black Opry event. Rose brought two things to the table: First, he already knew some of the artists, having previously played for The Kentucky Gentlemen, and second, as session players, he and his bandmates were well-versed in a variety of musical styles.

This second element was crucial, since the band would need to bring a different approach to nearly every song, shifting from the emotive pop-rock of Nicholas and the shimmering country-pop of The Kentucky Gentlemen to the torchy pop of Cannon and the rootsy hybrids of No, Pierce, and Timbo.

Due to the logistical difficulties of bringing everyone together, the band would not be able to rehearse the songs with the artists ahead of their set, a situation that required what Holly describes as “full-on trust” between everyone involved. Instead, the musicians and other members of the Black Opry crew would talk through the set during a “family dinner” at a shared Airbnb, the type of gathering that has become a central part of the Black Opry spirit.

“Holly is very intentional about trying to make sure we all have the opportunity to stay in the same place,” explains No. “It meant a lot to be able to share a drink with the band the night before, to talk about the songs, joke about other artists, joke about the industry. … That goes a long way toward making it feel like true camaraderie.”

Newport Folk booker Becca Peters first caught wind of Black Opry on Instagram, and she quickly put it on festival director Jay Sweet’s radar. After a little more digging, Sweet decided they were a natural fit.

“The thing that we really liked about it was the collaborative nature, because that’s Newport in a nutshell,” he says. “We kind of make sure we’ve maxed out the number of people we can get on the stage.”

Another selling point was that different members of the “folk family,” as Sweet is fond of saying, were willing to vouch for them. Sweet says that Allison Russell reached out to tell him about Black Opry, as did a member of Oladokun’s team.

“It was coming from all angles,” adds Peters.

For Holly, it was a big deal to be able to add Oladokun to the lineup, just as it was a big deal when Russell surprised the audience during the Black Opry’s Nashville debut at the EXIT/IN in December. She says the support of established artists is crucial to her mission of giving opportunities to artists who wouldn’t otherwise have access to them.

“I really want to use those spaces to bring people in who wouldn't get the opportunity otherwise, even though they're ready, artistically,” she says. “It's just that red tape that they haven't broken through yet.”

Making and Retaking History

One such act is The Kentucky Gentlemen, the twin-brother duo made up of Derek and Brandon Campbell, whose slick harmonies and pop-driven approach make them a perfect fit for country radio, if only radio would listen. For the duo, being at Newport meant feeling connected to a storied tradition.

“Every time we mentioned Newport to anybody, their eyes lit up. You immediately get a history lesson,” says Derek.

That history begins in 1959, with an inaugural lineup that included Odetta, Bo Diddley, and Reverend Gary Davis. Throughout the ’60s, the festival continued to book Black folk, blues, and gospel artists, including the Freedom Singers, who rallied for civil rights during the 1963 festival. More recently, Our Native Daughters made their triumphant debut at the 2019 festival, and Russell used her headlining set in 2021 — dubbed “Allison Russell’s Once and Future Sounds” — to center Black women’s voices and experiences.

For Sweet, honoring that festival’s inclusive history is “inherent in the DNA of the job.”

“I was given this job with a clear historical narrative,” he says. “This festival was literally created to house musicians who could not break through on the radio or TV at that time because they were different.”

It’s a familiar story for anyone who follows country music — the genre’s gatekeepers are famously exclusionary of anyone who isn’t white, straight, and male — but less attention has been paid to the ways in which Black artists are marginalized in folk and Americana. For No, giving opportunities to individual artists is one thing, but larger work needs to be done around educating people about folk music’s Black roots.

“In the folk world, there are a lot of what I would describe as mostly well-meaning but ignorant white people who think that they are doing you a favor by listening to your music,” she says. “I get a lot of comments that are like, ‘Have you heard of this person?’ and it’s someone extremely famous and foundational to the genre. Even if they like our music, they don’t see us as being at the center of folk music.”

She describes performing at Newport as validation of her work, tangible proof that she and her peers have a seat at the folk music table. She admits that she wasn’t sure what to expect going in because her experiences at other folk festivals are not always positive. However, she was pleasantly surprised.

“When I got there, I found the audience to be so attentive,” she says. “They were listening to the lyrics and they were very tuned in, and that was super affirming.”

During soundcheck, the Harbor Stage crowd spontaneously started cheering as The Kentucky Gentlemen sang a few bars of their song “Vintage Lover.” The duo had planned to perform only “Lose My Boots,” an uptempo cut from their new EP, but the audience’s reaction convinced them to add “Vintage Lover” to their set.

That feeling of spontaneity pervaded the Saturday evening Black Opry set, and there were many moments when the audience and the performers seemed mutually electrified. The audience was vocal in its support throughout, summarily rising to its feet during the final group number. (The Kentucky Gentlemen and Nicholas led the way on a cover of Chaka Khan’s “Ain’t Nobody,” a nod to the Queen of Funk’s epic cameo during Russell’s 2021 set.) Supportive as they were, the crowd was — it must be said — overwhelmingly white, which was not lost on the group.

“We had a pretty big entourage, probably about 15 of us, and walking through the crowd you could tell that people were surprised to see us,” Holly said afterward, reflecting on her experience at the fest. “It wasn’t really in a negative way, it felt more curious, but I would love to come next year and for it not to be a surprise for us to walk through the audience. And for that experience to be more reflective of the work that they do backstage.”

“You hope that as the artists get browner, the audience will too,” says No. “But I think that’s a puzzle that folk music as a whole has not yet solved.”

Get Lizzie No's firsthand view of the Black Opry's Newport set via this essay at Folk Alley.

Comments ()