The day Elvin Jones Fired Up Milwaukee’s Lakefront Festival of Art in 1972

This blog is a birthday remembrance, honoring — one month late to the day — the monumental jazz drummer and innovator Elvin Jones, who was born on September 9, 1927 in Pontiac, MI, and died May 18, 2004. His passing prompted the original version of this appreciation, published in 2004 in The Capital Times Rhythm section, aptly enough. Now, the photo-essay aspect was also prompted by Racine trumpeter Jamie Breiwick’s assiduous recent efforts at building an archive of Milwaukee jazz history, here. – KL.

Elvin Jones has driven the jazz spirit in my mind and body since before I knew it. Besides countless jazz drummers, he’d influenced the double-drummer approach of The Grateful Dead and The Allman Brothers Band, and the Coltranesque dramatic flow of the Butterfield Blues Band’s pioneering instrumental epic “East-West” of 1966, which he praised with a sage sense of the musical zeitgeist. 1

I had already caught the Coltrane bug, and Jones’ drumming coursed though my veins as I followed Trane’s incandescent, rhythmically refracted quest.

Jones’ innovative drumming style boiled all the implications of a time signature into rolling accents and a sliding pulse that pulled the listener in, and freed the music with a balance of sly sophistication and muscular resonance. As the most integral member of the classic John Coltrane Quartet, Jones went somewhat underappreciated by wide audiences after he left that group. This was partly because his approach was baffling to many even as you heard and felt its effectiveness and power to carry and lift the music.

Some drummers picked up on his triplet-figured rhythmic attack and started approximating his ambidextrous polyrhythms, which created a unique dynamic tension across the drum kit while requiring a loose-limbed bodily execution. (Jones succinctly describes his polyrhythms as “many rhythms, coordinated rhythms”) But few could capture the essence of his marvelous motion. That included monstrous press rolls to rival Art Blakey’s and a roaring sonic totality when swinging alongside a saxophonist as inspired as Trane in full locomotion.

At times you could hear Jones grunting and groaning as he played, and those bodily exhalations seemed integral to his sense of rhythmic dynamic and propulsion, like a tai chi martial artist. The analogy came to mind not because I know he had knowledge of, or had studied, that artful discipline. But I know he was married to a Japanese woman, Keiko Jones, who also wrote music, sometimes for her husband’s group.

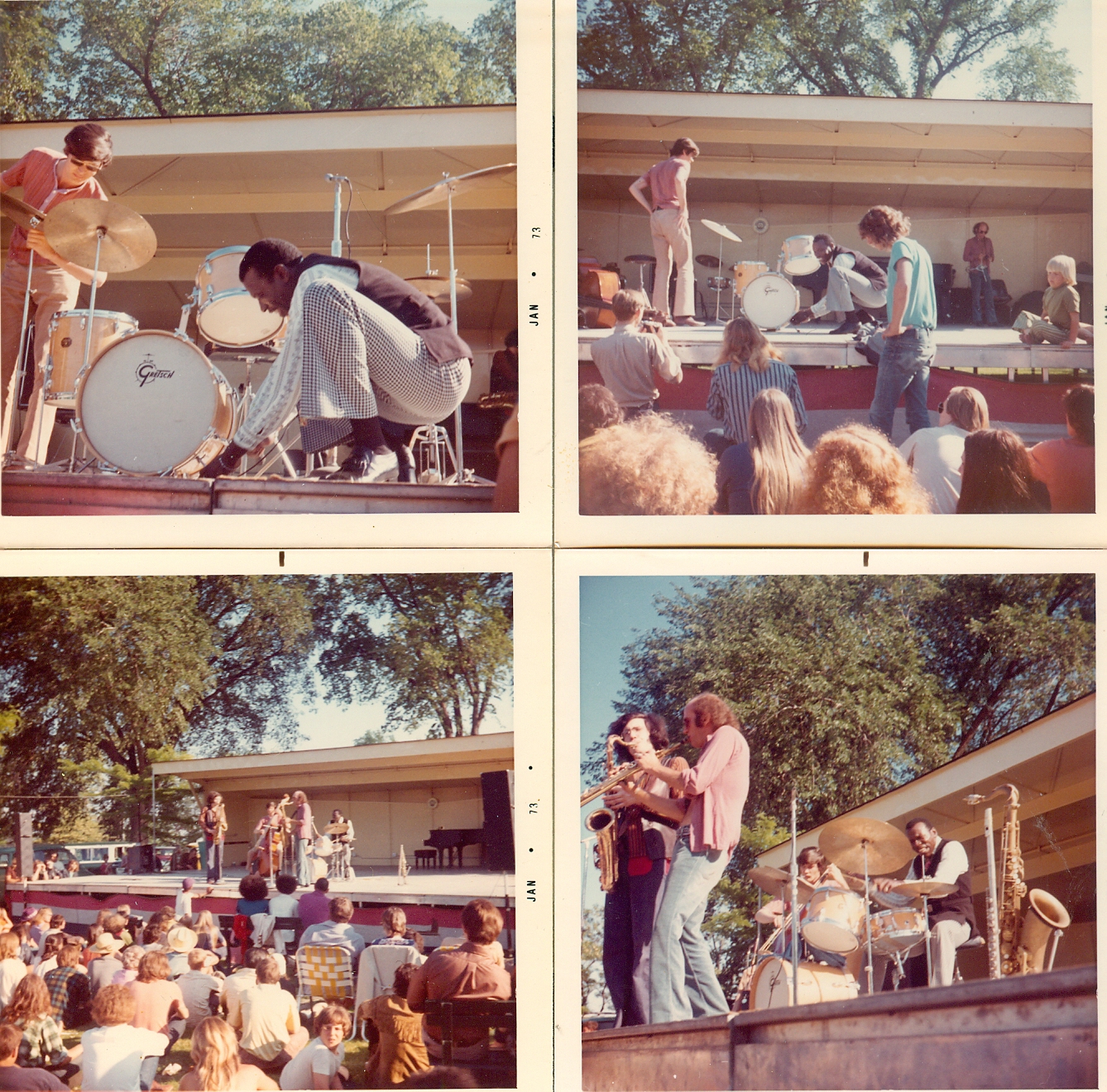

I recall hearing (and meeting Elvin and Keiko) in 1972 at Milwaukee’s Lakefront Festival of Art, which was the occasion of the photos I took, which you see on this blog. I was with one of my best friends, Frank Stemper, then a local jazz pianist who would soon become a composer, earning a PhD. in music (on which I collaborated with him on his final project) and becoming the long-time director of the University of Southern Illinois– Carbondale music department. Frank’s compositions has been performed worldwide, he has a sophisticated sense of musical time and was a big Buddy Rich fan. And yet, that day, intently watching and listening to Elvin, Frank finally exclaimed, “What is he doing?!” (More on that concert later.) 2

Clockwise from top left: (1) Elvin Jones played so powerfully that he had to nail his drums to the stage. (2) He chats with a fan while pounding. (3) His quartet essays an ensemble section and (4) the quartet is framed by the lovely setting of the 1972 Lakefront Festival of Art in Milwaukee’s Juneau Park, on Lake Michigan.

Racine-born, Wisconsin Conservatory of Music-trained bassist Gerald Cannon, who has played with many world-class jazz artists, commented “I was the last bassist to play with Elvin Jones. I was with the (Elvin Jones) Jazz Machine for about seven years, and I thought I knew how to play the bass before I played with Elvin. I was wrong. I learned more about dynamics, time, groove, and melody from Elvin than any band I had ever played with before him. I really learned to trust myself and my time with him. He was a great man. I miss him dearly. God Bless Elvin Jones.” 3

Indeed, Jones had evolved into a sui generis master musician with an ensemble concept which he developed in a series of superb albums on the Blue Note label. He showed that his post-Coltrane jazz would be diverse and subtle, but swinging and declamatory, and need not be deathly serious in manner.

Sadly a number of these albums remain un-reissued on CD. 4. So I don’t hesitate recommending wholeheartedly The Complete Elvin Jones Blue Note Sessions on the limited-edition label Mosaic Records ($128, mail order only at 203-327-7111 or www.mosaicrecords.com), an investment that is rewarding, pleasurable and a deep slice of obscured music from modern jazz’s greatest drummer. A debilitating arm injury prompted me to listen to the whole 8-CD set recently, but each album is worth savoring.

Jones’ wizardly multi-directional motion filled the rhythmic role of piano accompaniment and his coloristic approach to drum tones and savvy bassist Jimmy Garrison and reed player Joe Farrell provided a remarkably rich trio sound in his early Blue Note sessions “Puttin’ It Together” and “The Ultimate.” Farrell, who died in 1986 at 49, was a resourceful master of saxes and flutes, and would not be fully appreciated until his later work with pianist Chick Corea.

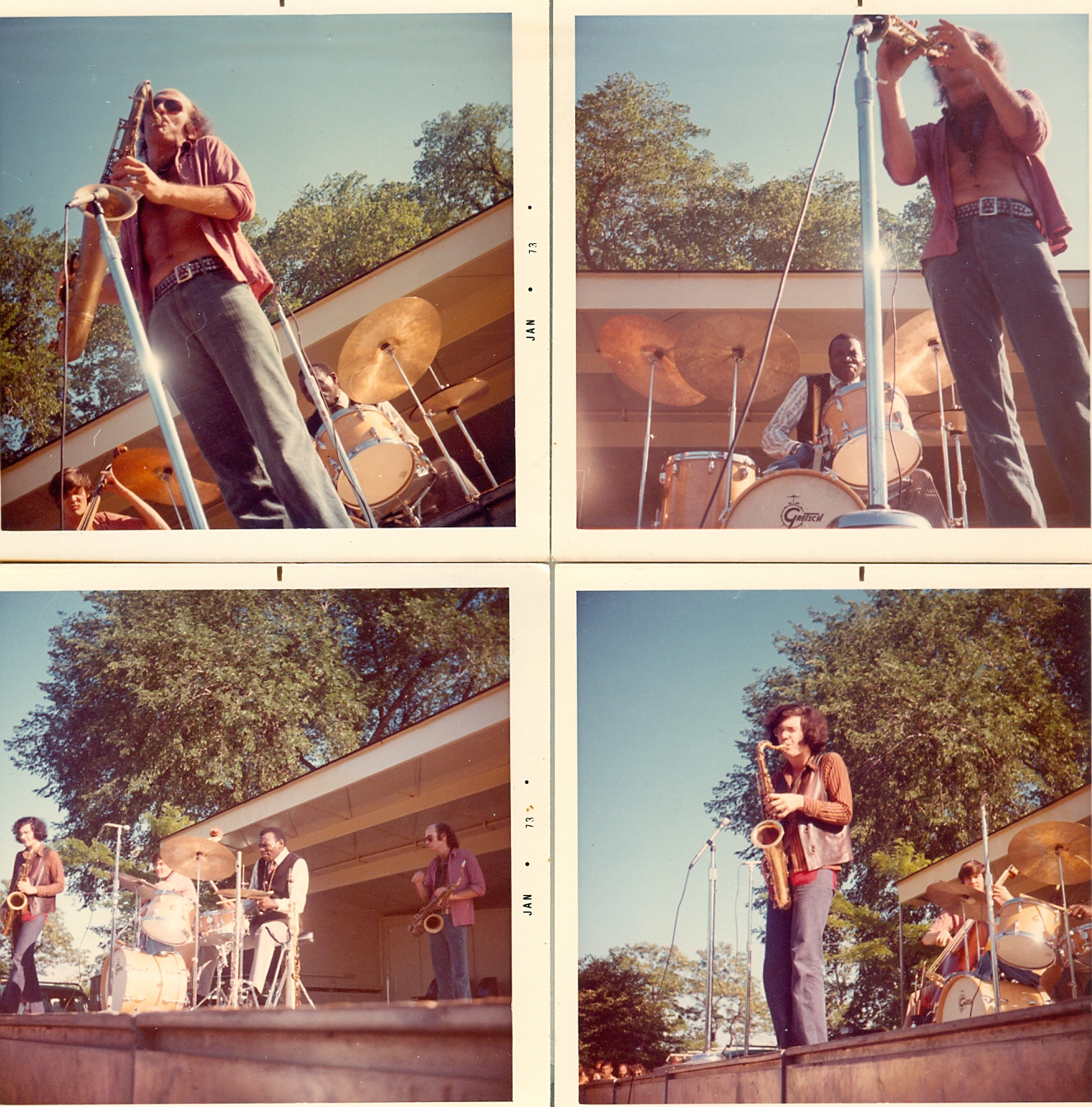

Farrell was a consistently delightful and inventive musical thinker on these dates. Jones expanded his ensemble on the albums Coalition and Genesis and especially on one of my favorite jazz albums of the 1970s, Merry-Go-Round. The date included the masterful baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams, ex-Basie tenor player Frank Foster and two young fiery Coltrane sax disciples, Dave Leibman and Steve Grossman. Merry-Go-Round had a carnivalesque variety and bristling joi de vivre, and among its highlights are Corea playing on the first recording of his small masterpiece of Latin jazz, “La Fiesta,” Liebman’s exultant hard swinger “Brite Piece” and bassist Gene Perla’s sassy strutter “’Round Town.”

Clockwise from top left: (1) With Elvin Jones at the drums, Dave Liebman solos on tenor sax, (2) then soprano sax. (3) Fellow saxman Steve Grossman tears it up (with bassist Gene Perla driving the pulse), and (4) finally Elvin Jones takes a drum solo.

I got a live earful of this great material at that unforgettable Lakefront Festival of Art performance. I also recall, near the stage, my dad Norm Lynch, a big jazz buff, hoisting my toddler sister Ann up on his shoulders, so she could better see and hear the fiery and sometimes blistering music. That muscular double-sax quartet (with Liebman, Grossman and bassist Perla) would soon produce an explosive multi-disc set called Live at the Lighthouse which is intact in the Mosaic collection as an edgy, thrilling exposition of the band’s creative power. Throughout this mighty box set, Jones’ flaming, indefatigable musicality illuminates lyrical chamber trios, Latin-style percussion jams, octets and expansive live sets.

Still, it’s worth remembering, Elvin Jones came of age with John Coltrane, so to fully understand, or at least experience, him one must hear that body of work, largely available on Atlantic and Impulse Records.

“With John, everything I had learned up to that point, it gave it significance,” Jones recalls of the classic John Coltrane Quartet, with pianist McCoy Tyner and bassist Garrison. 5 Having descended from the mountainous vistas of Coltrane’s spiritual expedition, Jones brought his own music somewhat more down to earth, wind and fire. And yet he could still take you on a journey that you can take nowhere else.

________________________

All photos by Kevin Lynch. This article was originally published in Culture Currents (Vernaculars Speak) http://kevernacular.com/?p=6713 and in shorter form in The Capital Times in 2004.

NOTE: One of the first women to break into the upper ranks of modern jazz was Marian McPartland. The pianist and her trio (pictured below), opened for Elvin Jones that day in Milwaukee. McPartland would later go on to host a popular NPR jazz radio program where pianists would visit her live in the studio, discuss their music and play live solos and duets with Marian.

- Elvin Jones — upon hearing Mike Bloomfield’s long and highly influential composition “East-West” on the Butterfield Blues album East-West — commented, in part: “Very well done. This has a nice feeling. I’d give that five stars.” – Down Beat Blindfold Test, Nov. 17, 1966.

- Perhaps the best elucidation of Jones and his innovative percussion approach is on the video documentary Elvin Jones: Different Drummer. It includes Jones’ own vivid and eloquent descriptions of his style and its effects, which was a multi-color-related concept, as he explains it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qn1xMVmLbWk A technically superior document of Jones in extended performance is the DVD Elvin Jones: Jazz Machine from a 1991 concert.

- Gerald Cannon posted his remembrance of Jones on the comments section for the Different Drummer You Tube (see link in footnote 2).

- Check the online All Music Guide for comments on availability of individual albums: http://www.allmusic.com/artist/elvin-jones-mn0000179379/discography

- The Elvin Jones quotes in this article are from the documentary film Different Drummer