THE NEW NORMAL: Bluegrass Goes High-Tech to Survive COVID-19

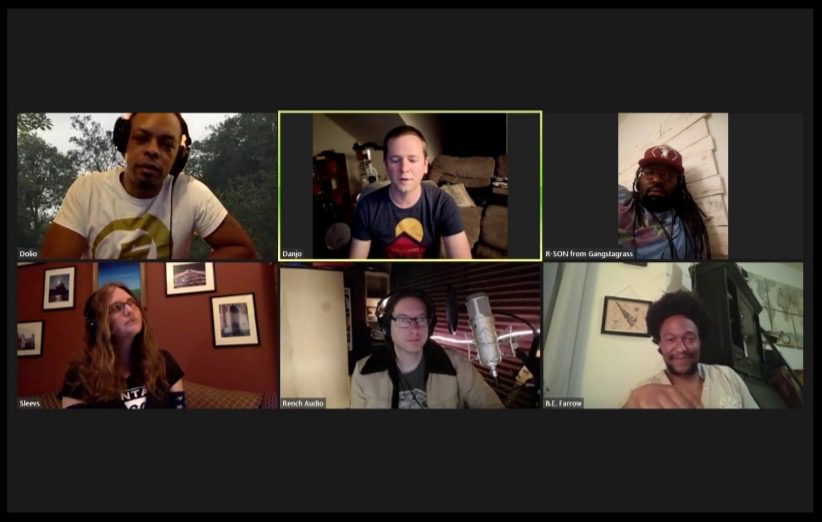

Gangstagrass on a recent Twitch stream. (Screengrabs courtesy of Gangstagrass)

EDITOR’S NOTE: “The New Normal” is an occasional series of stories that look into how the coronavirus has affected artists, listeners, and the music business.

In the span of just 24 hours, every festival, tour, and performance date Gangstagrass had on the books was canceled. The band, an invigorating infusion of hip-hop and bluegrass, was left with an uncertain future as the COVID-19 pandemic slammed the brakes on its main income stream. Instead of focusing on fear, though, the band has been leveraging its newfound tech savviness to explore more ways of bringing their music to their fans.

Dan Whitener, banjo player for Gangstagrass, said the band learned to stream on Twitch, a platform gamers use to stream Fortnite and Call of Duty. Whitener said he has been pleasantly surprised at the response from fans. Each time they stream, a different band member takes over, and because some members are bluegrass and some are from a hip-hop background, it’s always different.

“Individually the members have such different interests,” Whitener says. “What you see is really different night to night. That gets to the heart of what we are as a collaboration.”

The band also recorded its forthcoming album, No Time for Enemies, due out Aug. 14, entirely from their homes in order to practice safe physical distancing. The band used equipment they already owned, piecing the tracks together from afar — with members located New Jersey, Philadelphia, and New York — and led by their longtime producer and guitarist, Rench. Whitener said there were challenges in that approach, but that bluegrass’ simple instrumentation and hip-hop’s bedroom studio movement meant they were already somewhat prepared.

Other bluegrass bands are in a similar position — building on existing skills while learning new tactics to stay afloat. The Henhouse Prowlers are known for setlists that include bluegrass covers of songs from around the world, many of them learned during their time touring other countries through a State Department program called American Music Abroad that pays for American musicians to travel and build relationships with other countries, cultures, and artists. To put those experiences into action, the band in 2013 founded Bluegrass Ambassadors, a digital space for advocacy and education that has now added an online Bluegrass Ambassadors Academy to connect professional musicians with learners while everyone’s at home.

The Prowlers livestream shows with artists around the world, dedicating a portion of their videos to teaching children about music. They also fundraise for their partner musicians, providing much-needed financial support at a time when resources are scarce. Ben Wright, banjo player and founding member of the band, said he’s grateful for the innovation but acknowledges that there was a lot to learn as he went from a performer to an interviewer and lesson-planner. Tech was another struggle, Wright said, and he needed faster internet and new LED lighting to pull off digital content creation smoothly.

“When COVID hit, we leaned into our nonprofit because obviously we can’t perform right now,” says Wright. “We have time to educate ourselves. I definitely had a learning curve. You learn how to do it, and you fail sometimes.”

Wright says that fortunately, audiences seem to be forgiving of technical issues and are generally understanding because so many are also new to working from home. He’s grateful to provide lessons for kids whose parents are suddenly homeschooling, and for The Henhouse Prowlers’ global audience as well. The band has filmed COVID-19 informational videos for multiple embassies, including the Kyrgyz Republic and Ivory Coast. The band encourages viewers to stay home and wash their hands, and Wright said some of their videos have gone viral in various countries, likely because they built a fanbase on previous tours.

Venues and Organizations Adapt

Bluegrass bands and venues alike are gaining global recognition as performances shift online, even some more commonly thought of as local stalwarts. The Station Inn, an iconic Nashville venue for more than 40 years, has ramped up its streaming program since the pandemic began. Marketing Director Jeff Brown says Station Inn TV has now reached a total of 600,000 people since the club pivoted to streaming pre-recorded shows in April. The Station Inn held a few livestreams without audiences on site, but as the city shut down, so did those performances.

Station Inn TV is a subscription service, but it also offers nightly free shows. Those streams have reached people in 22 countries, according to Brown. Since the pandemic began, subscriptions are up by 30 percent, keeping the business in the black. Now, venues across the US are asking the Station Inn for help to set up their own high-tech streaming and camera systems.

“Roughly a dozen venues reached out asking for help,” says Brown. “We tried to work with them, but it’s not easy to set up. We’re very thankful we already have the tools in place.”

Meanwhile, the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) is also working to educate its members on how to adapt to a world without touring revenue with resources like the Bluegrass Community Resource Page, Online Concert Calendar, and Instructor Database (created with the American Banjo Museum). It also has been advocating for financial relief for musicians, joining 40 other music organizations and nonprofits in writing Congress to urge COVID-19 financial relief for artists.

This education, innovation, and advocacy may seem out of character for a seemingly lo-fi, traditional genre like bluegrass. Many of its artists tour successfully year-round without the help of social media. Some release albums exclusively on CD, skipping digital streaming or an online presence. But according to Whitener, these changes are needed in order for bluegrass to keep going and stay relevant.

“Do something different,” Whitener says. “But you don’t have to [completely] change. I play bluegrass banjo; I don’t significantly change the way I do what I do [online].”

Brown says bluegrass should be proud of its current leadership and the innovations musicians and venues have embraced. He believes that while COVID-19 may change some elements of performance, it won’t drastically alter more traditional styles or make them unrecognizable. It may just change the way fans consume the music, or introduce modern storytelling about current realities into the lyrics.

“This has impacted all of us. And it’s going to reach from Nashville to Atlanta, to people in India and Japan, who are fans of bluegrass music,” Brown says. “It’s going to change bluegrass slightly but I don’t think it’ll change the tradition.”

Whitener said it’s natural and healthy to contemplate the changes, and even to grieve missed dates and canceled shows. Keeping track of time by what should’ve happened and looking wistfully at the calendar, he says, is a constant reminder of what could have been, but a natural reaction for musicians out of work. However, that doesn’t mean there isn’t a light at the end of the tunnel, or that music will become any less important because it’s delivered in a different format.

“We worry that so many musicians aren’t going to be able to make a living, but the thing that won’t go away is the need for live music,” Whitener said.” If anything, it will make it so much more obvious that it’s a thing we need.”

While futures, festivals, and tour dates are uncertain, many in the bluegrass community are looking ahead all the same. Both the Henhouse Prowlers and Gangstagrass encourage bands without strong social media followings to jump in and start where they are, emphasizing how accepting audiences are of home setups and less-than-perfect streaming.

For if, as Brown predicts, bluegrass continues to evolve as the pandemic drags on, the genre will be led by a group of musicians working hard to preserve the art form, no matter the means of delivery or how it’s broadcast.

To comment on this or any No Depression story, please drop us a line at letters@nodepression.com.