The preacher they called the “Blues King”

The preacher they called the “Blues King”

by: Erwin Bosman (www.myblues.eu)

The bulk of the information comes from Dr. David Evans (°) who traced Ruben Lacy in 1966. I sincerely thank Dr. Evans for reading a draft of this essay and formulating very useful comments to it. The final version with its shortcomings remains of course my sole responsibility.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Too often the blues is only seen as a reaction from the African-American populace to the oppressive environment that it was brought to. While this view is certainly substantiated, as a single approach it seriously limits the comprehension of what the blues represent. More than only the result of a group’s passive reaction to the constraints imposed on it, the blues are the positive outcome of an intelligent, selective and complex process of acculturation of African-Americans to a social and cultural environment that was totally foreign to them. Stripped from everything but their spirits when they came ashore as chattel property in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, the slaves have engaged in creating a system of values that permitted them to interpret their New World environment. In this process, they built on the cultural memory from the African homeland and integrated, in a creative way, European cultural traits in their own African framework, often reshaping them to fit the new context. Before Emancipation, the African-Americans were largely forbidden the right to have a culture on their own; they were in fact not even thought of disposing anything else than barbaric and heathen customs and practices, hardly worth the name “culture”. After Emancipation, and especially after the abortion of the Reconstruction, their social segregation meant at the same time a cultural marginalization. Yet, within these narrow parameters set out by the white class, first of cultural disregard and then of marginalization, a black consciousness has developed that at the end of the day was neither African, nor European, but genuinely African-American. Therefore, I believe that an approach to the blues as a constituent of this positive construction of a broader black consciousness will tell us more than a restrictive formulation of the blues as only the result of a resistance against a social confinement and denial of basic rights during a particular period of time.

Focusing on the concept of black consciousness, the discussion on when, or where the blues were “born” becomes less relevant. What we need to look at, in the first place, is when certain musical, lyrical and other cultural expressions became to be defined by the African-Americans themselves as a significant translation of their consciousness. Furthermore, it puts the debate on the survival of African traits in the blues in another perspective. It is less important to ponder on rhythmic and melodic resemblance between certain African musical styles and the blues, than to see the latter as a component of a larger cultural system that African-Americans have creatively carved out for themselves to construct an identity in a society to which their ancestors were deported against their own will. The notion of black consciousness allows us, moreover, to explore how different cultural items are strongly interwoven. Authors such as L.W. Levine have for instance convincingly demonstrated how the folk tales, orally transmitted from one generation to another within the African-American population seamlessly complemented the emotions and considerations expressed in its dance and music. L.W. Levine has demonstrated too how humour plays an essential role in the African-American mind. The link between despair and humour in the blues is a clear reminder of this.

The backbone of the early black consciousness is an African world view that eschews a distinction between the secular and the sacred. “Wholeness” is a concept crucial to an understanding of the African spiritual perspective: the daily life is intrinsically mingled with the life of the ancestors and gods. In an activity such as the circle dance, transformed to the “ring shout” in the New World, the ecstatic, strongly rhythmic and emotional movements open the door to spiritual possession. Ancestors and gods are very real, living entities, who participate in the everyday life, and “are just around the corner”. It is only since the antebellum period that a cleavage between the secular and sacred realm became more pronounced in the African-American culture, paralleling the bolstered conversion efforts. After the Emancipation, the split was institutionalized by an often competing development of, on the one hand a wide range of black churches, and on the other hand the emergence of the secular music played in places such as the juke-houses. Though the profane-sacred rivalry was often very pronounced, some black churches defining the traditional black music as heathenish and barbaric, it was in practice not always possible to draw a clear division line between religious and secular music.

Against the backdrop of these considerations, I will now brush you a short portrait of one of the early, much underrated, bluesmen who had his musical career in the 1920s: Rubin Lacy. I hesitated to use the word “bluesmen” because the qualification “songster” or “musicianer” is often more adequate to cover the popular music performed by this generation of itinerant musicians, who played for both white and black audiences whatever the public asked them to play. In the words of a contemporary of Rubin Lacy: “Men, white, colored…we get on with them [get a music job]. White folks would give hayrides, dances. Then they’d get through. They’d have a dance at some kinda place, like a barn or something and we played. () We’d be make some money” (Ishman Bracey, in: Gayle Dean Wardlow, 1998).

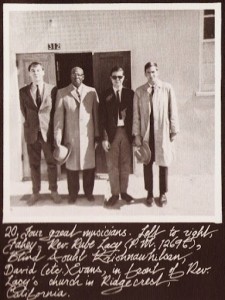

Unlike many of the performers of his generation, such as John Hurt or Son House, who have been “re-discovered” during the 1960′s blues revival, Rubin Lacy did not enjoy a second career as “a folk blues star”. Traced by David Evans in 1966, Lacy had given up on the blues to become a minister in the Missionary Baptist Church when, in 1932, he had faced death when he was seriously injured being struck in the leg by a loose brake shoe from a passing train. Though he was asked (“begged”, in his wording), after his decision to start preaching, to keep playing the guitar, he “just quit” and had given his guitar away.

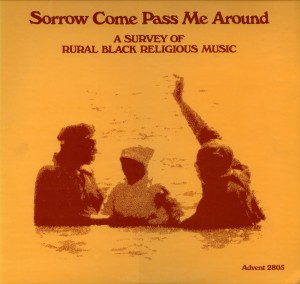

It is in his nature of pastor for a small community of African-Americans in Ridgecrest – a small town in the Indian Wells Valley, California, adjacent to a Navy’s research, testing and evaluation centre – that we can hear him sing “Talk About a Child That Do Love Jesus“, issued on the wonderful 1975 Advent LP (2805): ” Sorrow Come Pass Me Around – A Survey of Rural Black Religious Music” (1). Recorded on a Sunday afternoon in February 1966 by David Evans, John Fahey, and Alan Wilson (2), the song was a favourite of Lacy’s. It expressed, according to Evans, who wrote the liner notes to the LP: a deep personal meaning for Ruben Lacy and recalled him of his conversion and “dedication to the preaching despite many hardship.” His sole other recorded performance issued after his 1932 conversion is on the same LP, where his voice stands out in the background of a version of “Glory, Glory Halleluja“, recorded at a District convention in Ridgecrest of the Missionary Baptist Church in March 1966, with lead singer Chester Davis, Lacy’s deacon.

But let us first go back to 1901.

IN THE PATH OF GEORGE HENDRIX

Ruben Lacy is born in Pelahatchie, a small town in Rankin County, Mississippi, on January 2nd 1901, as the fourth child of a family of thirteen children. As an historical marker: Son House was born a year later, Charley Patton was then already a teenager, and Blind Lemon Jefferson, to name just one other, was eight years old at Ruben’s birth . His father, a fireman, died when he was only ten years old. Apparently the studious attitude that would later also motivate him to study hard to become a preacher, was already present when he was a child: he went to school for five years, combining it with afternoon work. From an uncle, he learned to speak German, and discovered “a great deal about history and world affairs” (Evans).

Though he was called a “peculiar” child, destined to be become a preacher (his grandfather was a minister), the siren of music sounded louder: hardly surprising, because music, mainly church music, was all around in the family both vocally and instrumentally (harmonica, guitar). His great example and inspirer was, however, the professional musician , George “Crow Jane” Hendrix, who not only had a “fine voice”, but was a multi-instrumentalist, leading a string band in Pelahatchie. Lacy said Hendrix played the blues then, and when he played the guitar, which he did extremely well according to Lacy, he either used his naked hands or a bottleneck. No records are known to exist from George Hendrix, but his traces popped up in the songs that Lacy later recorded in 1928.

Coincidence or not? Only a short time after the recorded blues took off in 1920 when Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” sold a million copies in one year, Ruben Lacy started his career as an itinerant musician crossing many county borders (Iowa, Ohio, Illinois, Mississippi). Taking up different jobs, as for instance rail road brake man and plantation overseer, we gather that music alone was apparently not always enough to win his bread, or that it was not even always his main activity at all. It was by the way as a rail road worker that he crossed Jimmy Rodgers’ path, the first major star of country music, and the then most popular white blues performer.

His teaming up, often in loose band formations, with other performers after 1923 in the Jacskon area reads like a “who is who” of the early blues, illustrating Lacy’s substantial role in molding the pre war blues format. From the interview with David Evans, we learn that he took up his playing with Son Spand (3), what “became the nucleus of a fast-growing group of excellent and important blues singers“. Charlie McCoy, eight years younger than Lacy, would “follow him like [Ruben] was his daddy”. Ruben appreciated Walter Vinson (Vincson/Vincent), also born in 1901, not only as a good guitarist but also as a fine singer. Vinson would later be a part of the famous Mississippi Sheiks with fiddler Lonnie Chatmon, and end up, after the Sheiks’ split, in Chicago where he had a second career in the 1960′s. By five years his senior, Tommy Johnson was another seminal figure of the elite circle of early blues performers to which Lacy belonged. Tommy Johnson’s tremendous impact on the development of the blues is largely underestimated. He combined a powerful menacing howl and haunting falsetto with a complex and technically-advanced playing style. His influence can be traced in the music of such legends as Howlin’ Wolf and Robert Nighthawk. An associate singer of him and Ruben was also Ishman Bracey, born just a week later than Ruben Lacy, and who learned his guitar playing from Lacy. As was the case for Tommy Johnson, the waxed legacy of Bracey is rather small. Gayle Dean Wardlow called him a “rare combination of braggart, entertainer, musician, showman” (1982). Bracey himself denied that he learned his style from Ruben Lacy (Wardlow, p. 54), and said that he “could play what Rubye Lacy played“, just as he prided on playing Tommy Johnson’s songs as well as he could. Bracey became, after World War II, an ordained Baptist minister, and stopped playing the blues. Luckily, he did not object advising the 1960′s blues aficionados whom he helped to rediscover Skip James, and also Ruben Lacy.

In David Evans’ opinion, Lacy was possibly the most prominent of this elite group of blues performers in the early 1920s. Though Lacy himself credited Tommy Johnson as the best all-round singer and instrumentalist, he nevertheless admitted that “when [he] was playing music in those days, [he] was called “the Blues King“.

When he set out for the Delta region around 1927, Ruben Lacy would continue his active and successful musical career, and bumped into some more of the early blues “who is who”. Son Househas told Stephen Calt that it was after seeing Lacy perform on a plantation in the Delta that he adopted Lacy’s bottleneck technique of playing (Beaumont). (4) The moaning and foot stomping on Lacy’s only two surviving records became features of Son House’s style. It is worth noting that Lacy and Son House shared a preaching background: Son House had started his Baptist preaching career already at the age of fifteen, and “got the blues” only around 1927. In one version of this turn in his life, Son House told that he “started playing the guitar in 1928, but [he] got the idea around about 1927. [He] saw a guy named Willie Wilson and another one named Rueben Lacy” (sic) (Beaumont).

During his drifting around through Delta towns, playing on the streets, he also met Charley Patton, who was then the hero of Son House. In his autobiography, David Honeyboy Edwardsstill reminisces his meeting with Ruben Lacy vividly:

“I used to stand around and listen at him. He was playing the “Hambone and Gravy Blues.” After he cut his little old record and it got on the jukebox, everything was, “Rube Lacy! Rube Lacy!” He was staying with this man out in Greenwood, and I would go to this house where he was staying. We’d gather up every night and we’d give him nickels and dimes. That’s the way he made it. We’d work all day for seventy-five, eighty cents a day and then at nighttime we’d go over there and give him those nickels. He made it playing his guitar.”

Also Tommy McClennan, one other guitarist and growler coming from the Delta, according to Greg Johnson, was influenced by the music and style of Ruben Lacy (5).

I HEARD BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON SNORE, I DO’NT KNOW HOW FAR

Shortly before Blind Lemon Jefferson died in December 1929, he had performed one or two weeks with Ruben Lacy in the Greenwood and Moorhead theaters (Ratcliffe; Uzzel). They met soon after Lacy’s Paramount record was released in 1928. Lacy trusted with David Evans that it was then “published that [he] was the best musician player there was in the South and Blind Lemon Jefferson was the best blues player there was in the West.” Lacy humbly corroborated this observation when he spoke of the qualities of Blind Lemon Jefferson. He had a good voice, but Lemon

“had everything in the same tune. I could play his songs, and he couldn’t play mine. If you notice well, nearly everything he played had the same tune to it. He had a kind of loping play. I could do it when I was playing back there. The fact of it, a lot of folks called me ‘Lemon’”.

I let you be the judge of this opinion. In any case, as an anecdote, Lacy remembered also vividly how he heard Lemon snore “I don’t know how far“, when they shared the same house.

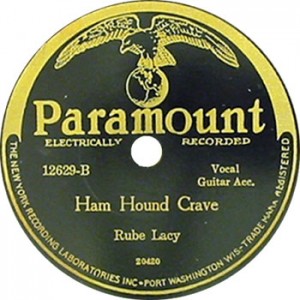

More serious now: it was Arthur Laibley, art director at Paramount Records – the same person who produced Charley Patton’s last session for Paramount – who had organised the meeting of Ruben Lacey and Blind Lemon Jefferson in Chicago in March 1928. In turn, it was Ralph Lembo who had liaised between Laibley and Lacy. Sicilian born Ralph Lembo owned a furniture store at Itta Bena, where he sold phonographs and records to the local black people, acting at the same time as local talent scout for Northern based record companies, much in the same way as Henry C. Speir did in Jackson. Lembo, who would later also accompany Bukka White, met Lacy in Itta Bena, and the meeting resulted in a trip, with some other performers, to Memphis where a Columbia Records mobile recording studio had been set up. Though no output resulted from Lacy’s Memphis confrontation with the record industry, it did lead to another journey, this time northbound to Chicago, where in March 1928 two of Lacy’s songs would be waxed and marketed on Paramount Record n° 12629 (6):

– Mississippi Jail House Groan (20419-2)

– Ham Hound Crave (20420-3) (with the voice of Ralph Lembo).

Both songs were learned from George Hendrix.

As mentioned above, David Honeyboy Edwards remembered well the second one, “Ham Hound Crave” (“Ham Hound Gravy”), which he called: “Hambone and Gravy Blues“, referring to the lines: “Mama got a hambone, I wonder can I get it boiled – Because these Chicago women, now, about to let my hambone spoil“. As Stephen Calt explains in his “Barrelhouse Words”, the slang “get (one’s) hambone boiled”, means to obtain sexual gratification. Male singers employed it as a term for penis. The Alabama born Ed Bell used it in a September 1927 Paramount recording, Ham Bone Blues, when he sang: “I got to move to Cincinatti, for to get my hambone boiled – Women in Alabama gon’ let my hambone spoil.”

Contrary to what one might suspect, “Mississippi Jail House Groan”, the other song, does not, according to what Lacy told David Evans, refer to time spent in prison. Lacy “never stayed in jail no time“. He “never been arrested for nothing but getting drunk, and [he] was soon out for that.” He used the “I”-form in the knowledge that the song would surely “hit somebody else“, that it would be “a truth” for somebody in his audience. Even as a preacher he would continue to defend the messages he brought in his blues lyrics: “I used to be a famous blues singer and I told more truth in my blues than the average person tells in his church songs.”

The reference to the “truth” is, I believe, an essential feature of the blues, even of the black consciousness in general, if we measure it against the prevalent values of the white, mainstream culture. It is what Kimberly R. Connor expresses when he writes that “the blues, like spirituals, is typically composed and sung not to answer the problem of evil () but to describe the reality of a situation in which evil is present. It is functional in the most essential way because the blues converts experience and renews existence by embracing life in all its aspects: sorrow becomes joy, work becomes play.” The blues reflect the reality, the “truth”, in all its painful and joyful – even plain sexual, bodily – aspects; it is not about romantic sentimentality, but about a very real, tangible and often cruel world inhabited by the performer and his audience. As L.W. Levine put it: “For so long black song had been the outlet for expressing deeply held attitudes concerning justice, whites, working conditions, and other primary concerns, it is not surprising that it continued to be a channel for articulating truth in the affairs of personal life.” The black consciousness’ approach to life stands in sharp contrast to the main features of white mainstream values that often ignore the harsh realities and indulge in a world of fairy tales, make belief, child hood fantasies, idealization and impossible dreams (7).

The fact that the blues performer uses the “I”-form is a consequence of an ever growing emphasis during the second half of the nineteenth century on the individualist ethos, typical for a society that places a premium value on the individual effort to obtain success. It was this development that made it possible that, contrary to essential African communal values, the “solo music” of the blues found its ways both in performance and content. But, although the expression of feelings, experiences and fears of the solo persona became the starting point of the performance, at the end of the day these were only the outer layer. Just as Ruben Lacy sang in personal terms about a jail house experience, what he did was to present difficulties that were all too common in his group, and that somewhere “hit somebody else, ’cause everything that happened to one person has at some time or other happened to another one. If not, it will…“. The ‘I’ and the “we’ merged in a common understanding of reality, of the “truth”.

The song not only belongs to the best of what folk blues has to offer, it is thus also highly representative of what the blues culturally stands for.

Though the 78record sold moderately well, Lacy decided not to record again in the studio, feeling that – compared to Lembo – his financial rewarding was not worth it.

A FUNNY PREACHER WITH A HEAP OF BLUES

The Blues were good times music too, and Ruben Lacy acknowledged unambiguously that when he played the blues, he was having fun. His music, he said, was entertainment, because everybody loved to hear him play, just as he loved to play the music. Clearly making a distinction between the feeling of ‘blues’ and the feeling when singing ‘the blues’, he stressed that before his 1932 conversion, though he wasn’t lively all the time, many times he had everything he could wish for, “all the liquor, all the money (), and more gals than () needed“. Why would he then feel the blues? Lacy:

“When I was in the world, I got as much of the world as I needed. I’d play sometimes better and everything when I was feeling good..Sometimes I’d lay down at night, wake up the next morning and get my old guitar and just tune it up and go to playing something I never played before.”.

In some way, after his turning a preacher, he continued to “tell the truth”, admitting however that “the blues is just more truer than a whole lot of the church songs people sing.” “I’m a funny preacher“, he told David Evans, because he openly stated to the people of his Congregation that you can’t sing about “taking a vacation in heaven“. This is simply not the “truth”, because when you take a vacation, you come and go. The truth is, saying, as one does in the blues: “I never missed my water ’til my well my well went dry.” The truth is when you “got a wife and she quit you ().” When she leaves you and you want her back home, that is when you feel the blues, when you experience “the truth“. “I had to sacrifice“, continues Lacy, “I had to put down something to go preaching. () And I’ve had a heap of blues since I was preaching...”.

Not only did Ruben Lacy thus not cover up his blues career when he became a preacher, on the contrary: he remained proud of it. Unlike others such as Ishman Bracey, he did not consider his blues period as something to forget, he was well aware of the major contribution he had made to the blues, which he considered like the church songs as a way to reach out to the minds of the people. Only, as David Evans expressed, “he saw religion as a higher calling and would undoubtedly have wanted to be remembered best for making many people happy in the church rather than on the dance floor.”

DAVID EVANS AND BRUCE ROSENBERG : HOW BLUES AND PREACHING MEET.

Had it not been for David Evans, we would have known little or nothing about this seminal figure of the early blues, who has contributed to its shaping as much, if not even more, than popular figures as Charley Patton or Son House. It was in 1966 that Evans met him in Ridgecrest, California, where he was the minister for a small African-American community, mostly migrants, like him, coming from the Deep South. In cooperation with John Fahey and Alan Wilson, an important amount of biographical data were registered, as well as spiritual songs. Not all of it, has yet been released (8)

One year later, in 1967, Ruben Lacy collaborated also with Bruce Rosenberg, in an investigation into the American folk preacher’s art. Rosenberg taped his source material in Oklahoma, Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and in California, Rev. Rubin Lacey being one of the more successful and inventive performers the scholar met. Folk preaching is an authentic and predominantly oral, spontaneous form of sermon, inspired and driven by a strongly interwoven knowledge of the bible with personal life experiences. Rosenberg quotes a number of Lacey’s sermons which, though formally referring to biblical passages, are in fact clearly inspired by popular songs that are not even spirituals. He noted that Rev. Rubin Lacey having been a blues singer “the lyrics of many songs should be expected to be racing around his memory and to find their way out in spontaneous sermons” (Rosenberg, p. 698). I believe that Rosenberg’s study would have been complete if he had connected more to the original African oral art traditions as they have been brought to America by the slaves and which, through rites as the “ring shout”, have found their way in the early, primitive slave spirituals. It would not have been hard to see in the sermon style of Ruben Lacy a continuation of these same, early techniques, when the division between the secular and sacred was not yet strongly institutionalised (9)

In any case, the focus on one and the same person by both a blues scholar and a researcher in preaching techniques is a further illustration of a largely false cleavage between the secular and sacred, which is fundamentally foreign to a culture that gave rise to both the blues and the spirituals. In his liner notes to the 1975 Advent LP ” Sorrow Come Pass Me Around – A Survey of Rural Black Religious Music“, David Evans observes that most of the selections of religious music and gospels on the album were not recorded in church services or from professional or semi-professional gospel singers. Instead, most of the songs were recorded at the people’s homes or at friend’s gatherings. Religious music can be song by women while doing their housework, or in the evening for the pleasure of the family, or even at work. Moreover, some of the tunes of the church songs on the album have been used elsewhere for secular songs and dance pieces. Blues singers and preachers share a number of functional similarities (10), and Ruben Lacy is a pure illustration of it. The blurring of the secular and the sacred in both gospel and blues reflects how both were deeply rooted in a common history and culture, in a shared black consciousness. Like it is the art and skill of a preacher to respond to, engage, and raise spiritual energies during a sermon articulating the search for freedom and the truth of the black experience, so it is the art and skill of a blues singer to create the energy by which more immediate relief can be found through a sharing of common, real life experiences.

To conclude with a quote from Lacy, referring to an anecdote in Moorhead, Mississippi:

“I was sitting there playing the blues, and two big preachers walked up to me and chucked some money into my lap. They said, ‘Play that again’. I played it, the blues too. And them preachers said to me, ‘If I had your voice, I could move mountains’. And since then I have with that same voice pretty well removed mountains. I have convinced and converted many a man.”

________________________

(°) Dr. David Evans, Professor (A.B.-Harvard University; M.A., Ph.D.-University of California, Los Angeles), directs the Ethnomusicology/Regional Studies doctoral program of the Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music. Dr. Evans is a specialist in American folk and popular music, particularly blues, spirituals, gospel, and African-American folk music. He is the author of Tommy Johnson (London: Studio Vista, 1971), Big Road Blues: Tradition and Creativity in the Folk Blues (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to the Blues (New York: Perigee, 2005), and has written many articles in academic journals, chapters in books, reviews, and dictionary and encyclopedia entries. Dr. Evans has produced over thirty albums and compact discs of field and studio recordings of music for the University of Memphis’ High Water Records. In 2003 he won a Grammy® award for “Best Album Notes.” He performs blues music and has made many concert appearances as a soloist (with guitar) and accompanist in the United States, Europe, and South America, and in the Mid-South region with the Last Chance Jug Band. He joined the faculty at the University of Memphis in 1978.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

NOTES

(1) Probably, this vinyl LP will be re-issued soon by “Dust-to-Digital” (note written March 2012)

(2) Al Wilson had two years earlier accompanied Son House in picking up his pre war repertory and would a year later make fame as lead singer of Canned Heat.

(3) No further information on Son Spand is available. Dr Evans told me over email that not even his first name is known. Spand was a phonetic spelling, referring to a common surname in Central Mississippi. Some extra research remains to be done here.

(4) David Evans notes that between Calt and Beaumont there is some confusion: Lacy didn’t play bottleneck. Son House, as Al Wilson points out, learned slide guitar from Willie Wilson or James McCoy.

(5) McLennan has never been interviewed. Lacy himself remembered McClennan from Greenwood (information from David Evans)

(6) See: http://www.wirz.de/music/laceyfrm.htm

(7) See also: “Isolement, individualisme et origines du blues”, translation Robert Sacré, in: Sentiments doux-amers dans les musiques du monde; editor: Michel Demeuldre, Pars, L’Harmattan, 2004, pp. 261-271.

(8) David Evans informed me that he disposes of quite some material of Lacy, and song recordings of him and his church members, not all of which he believes has yet been transcribed. He plans to do box sets of his field recordings, including Lacy material (his email to me, dated 13th March 2012).

(9) Rosenberg was not a music expert. It was David Evans who was contacted by Rosenberg, upon someone else’s recommendation. Lacking contacts himself (Rosenberg’s Jewish background was likely a handicap creating a distance with the genre and context) David Evans suggested to contact Lacy as a preacher; Lacy was probably to be cooperative (email from David Evans).

(10) See also: Charles Keil, Urban Blues, 1992.

Sources

http://www.msbluestrail.org/_webapp_2188661/Rubin_Lacy

http://www.cascadeblues.org/History/TommyMcClennan.htm

– Philip R. Ratcliffe: Mississippi John Hurt: His Life, His Times, His Blues, 2011

– Robert Uzzel, Blind Lemon Jefferson, His Life, His Death, and his Legacy, 2002