THE READING ROOM: After Nearly 50 Years, Hemphill’s ‘The Nashville Sound’ Still Resonates

Over the past decade, Nashville has become almost unrecognizable to anyone who’s been there a while. New apartment buildings spring up every day, and mammoth hotels break ground even as older buildings are imploded across town. Music Row, that venerable stretch bounded by Sixteenth Avenue South and Seventeenth Avenue South, started changing in the 1990s, and even within this past decade the famous RCA Studio was almost sold. I can remember hanging out at the Slow Bar in East Nashville, around 2000, to see Kenneth Stringfellow perform in this tiny dive bar in the “dangerous” part of town. Now the Slow Bar has been replaced and East Nashville is the hip part of town, though truth be told it’s still evolving, so that one side of the street might be dotted with 500-square-foot apartments renting for $1,500 a month while the other side of the street might be dotted with run-down shotgun houses. Those houses are fewer and farther between these days, of course, as newer buildings start to rise.

A plague of Bird scooters and pedal taverns — and recently a flock of ATVs running rampant in the streets — marks, or mars, downtown Nashville these days, and the character of Lower Broadway changed as soon as they built Alan Jackson’s AJ’s Good Time Bar, a four-story entertainment complex with food, booze, and music available on every floor. Jackson’s place was soon joined by similarly sized establishments run by Blake Shelton and Luke Bryan.

But at the heart of Nashville lies music, especially (though not exclusively) country music. It might be possible to trace the changing face of country music by looking at the changing face of the city. While Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge still sits across the alley from the Ryman and still stands as a place where you’re likely to hear Kitty Wells and George Jones blasting from the jukebox, just across the street you’re just as likely to hear a different music called country coming out of AJ’s, a music that has more in common with rock than with country. Questions about the authenticity and purity of country music are hardly new and, even 45 years ago, the then-new “Nashville sound” had traditionalists shaking their heads and wondering about the future of country music. The same conversation has swirled around “bro-country,” “hick-hop,” and other styles of country music, of course.

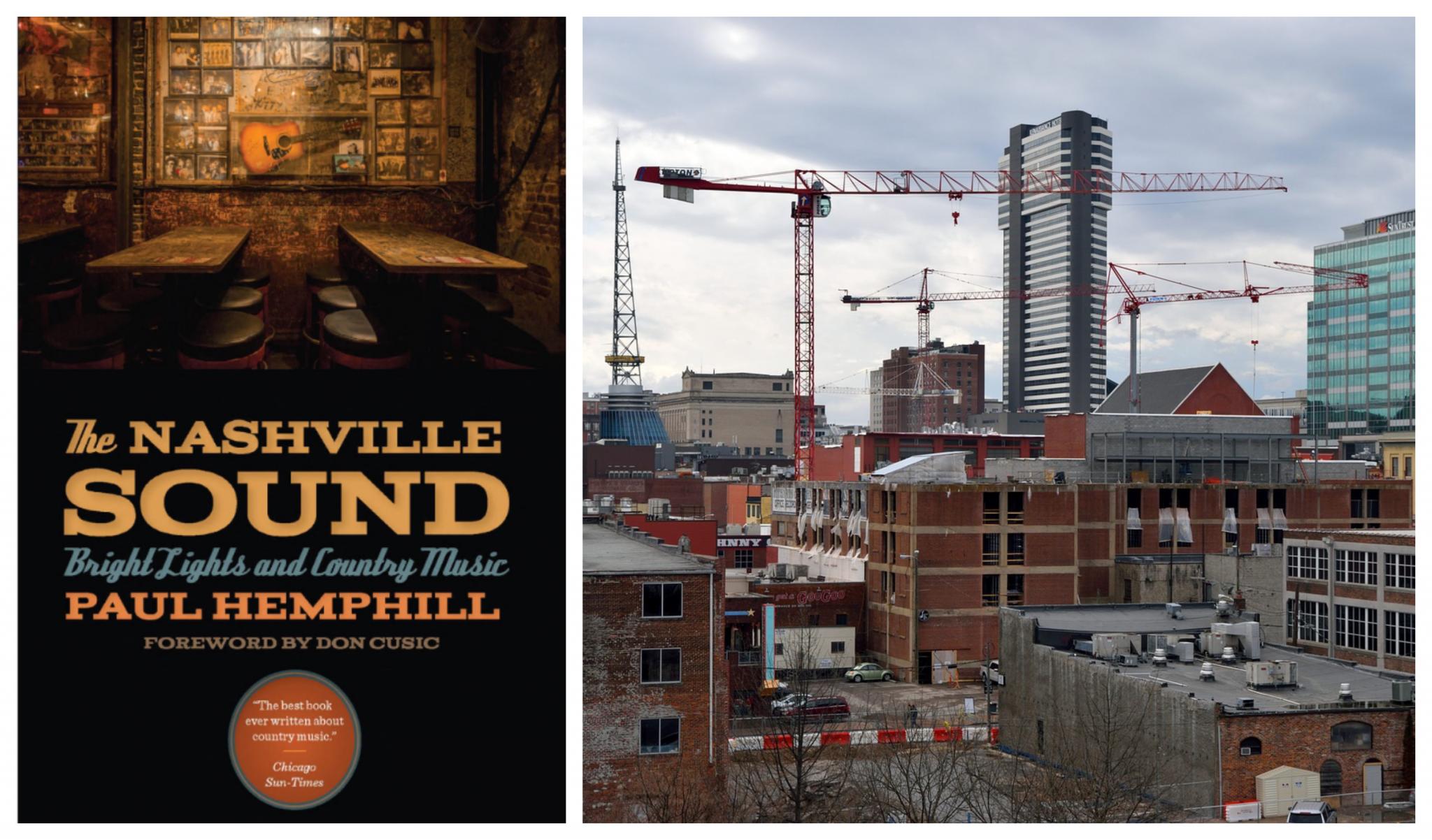

In 1970, Paul Hemphill, who was then a columnist at the Atlanta Journal, wrote a now-classic account about this collision of old and new Nashville. Reading The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country Music. Hemphill’s book was published originally in 1970 by Simon and Schuster and was republished in 2015, with a new foreword by country music historian Don Cusic, by the University of Georgia Press. In it, we have an opportunity to witness the truth of the adage “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” Many of the same questions motivate journalists and critics: What is country music, and how does Nashville embrace and reflect the tradition of country music while recognizing and embracing the new styles of country music? For the book, Hemphill, who died in 2009, lived in Nashville for two months, saw “a dozen performances of the Grand Ole Opry,” and interviewed 150 people, including Chet Atkins, Owen Bradley, Jack Stapp of Tree Publishing, and even some aspiring songwriters sitting next to him at Tootsie’s. The book includes profiles of Atkins, Glen Campbell, DeFord Bailey, Tex Ritter, and more, and Hemphill also traveled to Bakersfield, CaliforniaNashville West” — to talk to Buck Owens.

During his conversation with Hemphill, Ritter drives right to what for him is the nature and purpose of country music. “There’s one boy in town that writes kinda gutty stuff. I remember he wrote one about the neon lights and the guy gets him a bottle and he’s driving around the motel ’cause his wife’s in there with another guy. Well, so it happens. So it’s realistic. The rock ‘n’ roll kids, the folk-rock, they’re taking care of all the protest stuff. You see, I don’t want country music to fall into all of that. I don’t mind to sing about mother and home and flag all of the time. Sing about the back-street affair, naturally, and tell it like it is, get down to a little nitty-gritty. But I hate to see us fall into that category, and it looks like we’re headed a little this way. Country music has always been a rather, a wholesome kind of music, and I would hate to see it go the other way. It’s already happening, you know, the suggestiveness, the dirty — I find a little suggestiveness in this ‘Harper Valley PTA,’ for instance.”

Hemphill’s remarks on Music Row and its evolving character might just as easily have been written today: “The upshot of it all, Music Row, bears no resemblance whatsoever to the days of the Castle Studio and medicine shows and portable recording equipment. The stream-lined offices of Acuff-Rose Publications … away from The Row on Franklin Road, house a studio and a talent agency and even a printing shop … The latest word in engineering in 1957 was three-track tape, but now anything less than eight-track is considered quaint, and the newest studios are putting in sixteen track. (‘That’s for people who aren’t sure what they want to do,’ sniffs Owen Bradley.)”

There’s so much in The Nashville Sound that sounds as if it could have been written yesterday, though, of course, some of it seems a bit dated (the reference to 16-track recording equipment, for example). Yet, Hemphill’s dynamic, folksy, wide-ranging writing offers a snapshot of music — and a way of approaching country music that became known as the “country music industry” — and the city of Nashville that reveals the deep ways that the city and the music are intertwined. Hemphill also illustrates that questions about the authenticity and purity of country music will always be with us. The Nashville Sound is a must-read for anyone interested in country music; it remains a classic.