THE READING ROOM: Art, Music, and History Merge in ‘Hanging Tree Guitars’

Art and music help us dwell along the permeable boundaries of the physical and the spiritual. In and through their work, artists and musicians strive to evoke the sacredness of place, to transport viewers and listeners to a different world, even if only momentarily, to capture feelings of anger, joy, and sadness we associate with certain events, people, and places, and to render those feelings so palpably that we feel as if the artists are speaking directly to us. Some artists make guitars, or other instruments, as a way of capturing in the body of a musical instrument a certain tone, a certain feeling, that resonates with the artist and might resonate with the right player. In so many ways, a guitar or a ukulele or a violin or a bass chooses the player. You can ask any guitarist, for example, why he or she chooses and plays a certain instrument regularly, and faithfully, even though he or she owns 50 or a hundred guitars, and the answer will often be “the tone of the guitar,” “the richness of the sound that flows out of this wood,” or “no other guitar has the warmth of this guitar.”

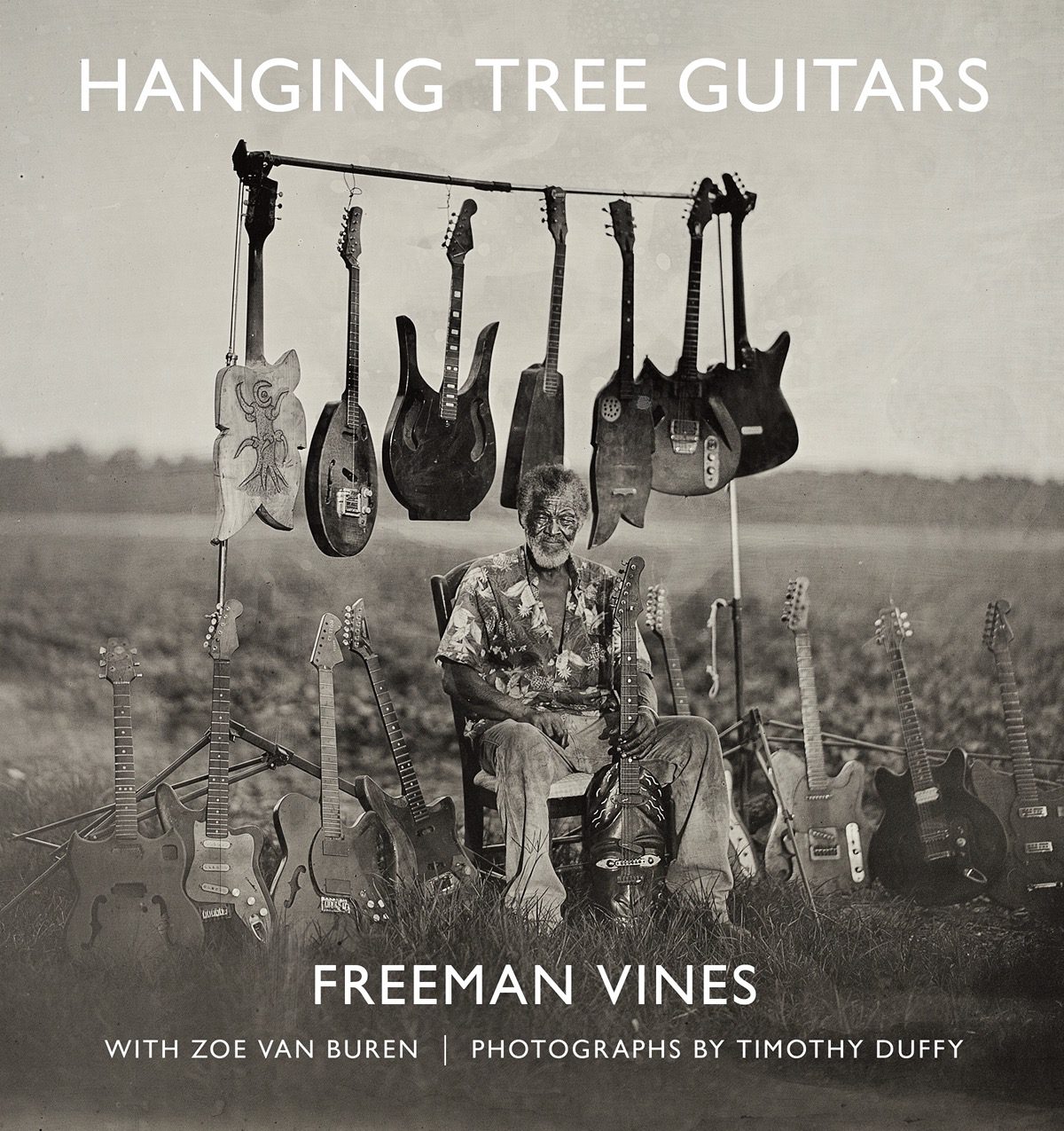

Great luthiers — those who make guitars and other stringed instruments — search constantly for the wood that will speak of the place where it grew, that will tell a story, that will resonate with the soul of a musician who picks it up and hears that story and who can coax those stories out the instrument. North Carolinian Freeman Vines is one such luthier, though until now his story has been little known outside of his small patch of ground in eastern North Carolina. Thanks to folklorist Zoe Van Buren and photographer Timothy Duffy and the Music Maker Relief Foundation, Vines tells his story in his own words, illustrated by Duffy’s captivating and stunning black-and-white photos, in Hanging Tree Guitars (Bitter Southerner).

The book takes its name from a series of guitars Vines carved from the wood of a hanging tree. When Duffy first met Vines in 2015, Vines had two planks of black walnut wood — “two-toned with light sides and a dark inner core.” The man who gave Vines the wood claimed that a man had been lynched on the tree from which the planks came. According to Van Buren, “on the day he brought the wood back to his porch, Vines made two sketches on a manila folder, thinking over the thin scraps of information he had been told about the wood. On the front of the folder, he drew the outline of a tree, a thick rope around its longest branch tied to the head of a simple, spadelike guitar. On the other side, a grimacing sharp-cheeked skull hangs from two parallel lines, a disembodied limb.” Vines set the planks and the drawings aside, but eventually returned to them a few years later to make this small series of guitars that Van Buren calls the “symbolic crux of the collection” of Vines’ more than 70 guitars. As she observes, “they offer an unsettled — and unsettling — look into how history is written into the land and the mind.”

Born in the 1940s, Vines grew up in Greene County, North Carolina, where the state’s eastern Piedmont meets its coastal plain. Growing up, there were billboards along the roads that read: “You are in Klan country: Welcome to North Carolina.” The third of 10 children, Vines worked alongside his brothers in the fields while his sisters went to school. By the time he was 14, he was jailed for selling moonshine to “someone other than a white man,” and he spent the next few years in and out of jail. He met someone in prison who taught him to read, and Vines developed an interest in theology and the occult. While his sisters traveled as the gospel group The Glorifying Vines Sisters, Vines traveled his own spiritual path, becoming a luthier, a sideman guitarist, and mechanic.

As Van Buren points out, “Although Vines pursued his own spiritual path, echoes of his family’s history on the land are audible in the more than seventy-five hand-built instruments and sculptural pieces that make up his life’s work. Vines built guitars in pursuit of a tone that he had once heard from the guitar of a gospel musician and never found again. Old, experienced wood saturated with years of use came closest to achieving the tone Vines sought, and he worked exclusively in found materials sourced from the landscape around him. Tobacco-barn steps, mule troughs, and piano soundboards became Vines’ most valued raw material. Still, the tone itself could only be accessed in what Vines describes as a ‘pre-mediation’ state. The guitars are imbued with this legacy of the spiritual from the first moment of Vines’ hand upon the wood.”

Vines’ words are laid out in the book almost like stanzas of poetry (or song lyrics), perhaps to capture their rhythmic, hypnotic tone. He reflects on his process, for example:

It’s hard to explain what it is,

and maybe it’s a feeling.

But it’s a tone.

You’ve got to be in a pre-meditation stage to experience it.

I’ll tell you something else too.

If the Gibson guy and Leo Fender were around to hear my instrument,

they would want to know what I did.

On working with the wood:

Sometimes wood has a characteristic it wouldn’t do what it wants to do.

By the time you think you got it, finished it, it messes up.

In pieces. Too deep. Found out it has cracks you didn’t see.

But I learned how to deal with them.

What makes a wood bad is the history behind it.

On the reason he continues to make guitars:

Why am I making all these guitars?

Well, they kind of make me happy, to tell you the truth.

Every time I say don’t mess around no more, I find myself still doing it.

Everybody needs something to do.

When Duffy asks Vines if Vines thinks there are spirits in the hanging tree wood, Vines replies:

You know they are.

They’ve got to be.

They’ve got nowhere else to go.

The wood, actually everything, is involved spiritually.

A little spirit rubs off on everything.

The very best way to read this book, of course, is to sit in a quiet place and listen to Vines’ own words and to gaze at Duffy’s photos. It’s not unlike reading James Agee and Walker Evans’ classic narrative of Southern sharecroppers, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and it possesses that same evocative power that allows us to enter a time, a place, a life not our own so that we might grow to become more expansive in love and life.

Vines’ Hanging Tree Guitars exhibition opened in June 2020 at the Greenville (North Carolina) Museum of Art and runs through December 2020.

On Sept. 25, a companion album with the same title as the book will be released. The album, a compilation drawn from the archives of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, and produced by Duffy and Aaron Greenhood, features two previously unreleased tracks: Johnny Ray Daniels’ “Somewhere to Lay My Head,” played on a Vines guitar, and Faith & Harmony’s “Victory.” In addition, the album includes the Glorifying Vines Sisters’ “Get Ready.” The album’s tracks, which range from the blues to sacred music, much like the words and photos in the book confront racial issues head on.