THE READING ROOM: Artists Reflect on Mickey Newbury’s Songwriting and Career

“Mickey Newbury simply sang with soul ablaze. After all, the long-time Nashville-based singer, a criminally overlooked artist during his lifetime but his generation’s most successful songwriter, owned an otherworldly tenor demanding fire from deepest depths.”

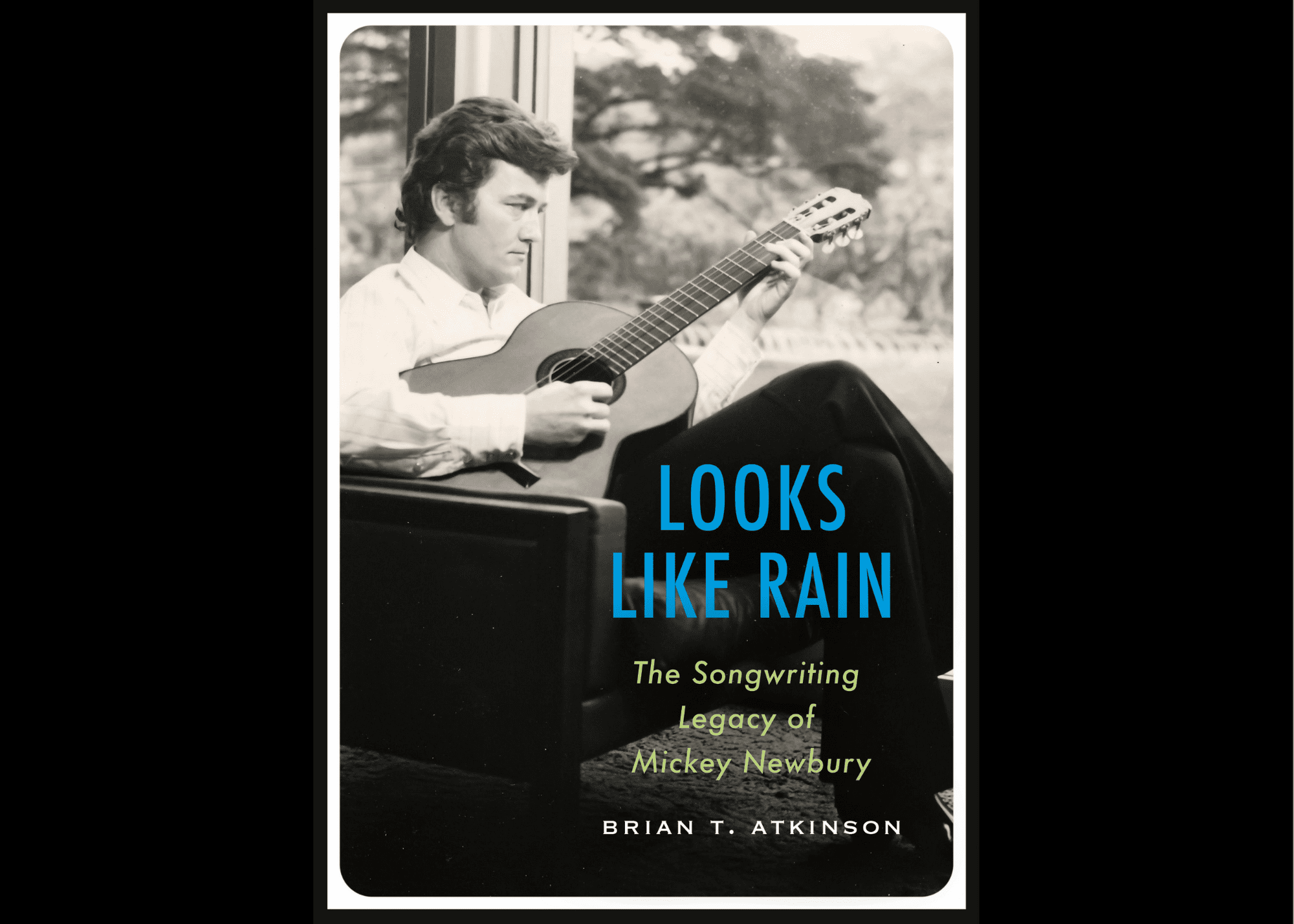

So writes Brian T. Atkinson in his captivating new oral history, Looks Like Rain: The Songwriting Legacy of Mickey Newbury (Texas A&M). As he did in his I’ll Be Here in the Morning: The Songwriting Legacy of Townes Van Zandt and The Messenger: The Songwriting Legacy of Ray Wiley Hubbard, Atkinson gathers a chorus of voices of artists whose songwriting and music Newbury’s artistry influenced and continues to shape. As Larry Gatlin points out in the foreword, “Mickey Newbury deserves a book because people don’t know about him … He was a great songwriter who championed my cause.”

In his prelude to the book, Kris Kristofferson recalls Newbury’s impact on him: “Mickey meant so much to me as a songwriter. I’m sure I never would have written ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ or ‘Sunday Morning Coming Down’ if I had never met Mickey … Newbury [was] such a resolute artist. He [was] never going to compromise his vision of what the whole picture should be … I learned more about songwriting from Mickey Newbury than from anybody. [His] simple lyrics and simple melodies worked to break your heart. He was my hero and still is.”

Born in Houston in 1940, Mickey Newbury started playing with a group called The Embers when he was a teenager. The band played local clubs and opened for Johnny Cash and Sam Cooke. As Texas music historian John Nova Lomax recalls: “Mickey was like John the Baptist to the scene. Mickey and Willie Nelson were both here from 1959 to 1961. Willie wrote his best songs then, and that was right when Newbury was coming up … He doesn’t get enough credit for being the spiritual godfather of Townes, Guy, and Steve Earle.”

At 19, Newbury joined the Air Force and served for four years. After he got out of the service, Newbury moved to Nashville, where he signed with Acuff-Rose Music. Don Gibson recorded Newbury’s “Funny Familiar Forgotten Feeling” in 1966, and in 1968 Newbury scored four top-five songs on four different charts: “Just Dropped In (to See What Condition My Condition was In)” on the pop/rock charts; “Sweet Memories” on easy listening; “Time Is a Thief” on the R&B charts; and “Here Comes the Rain, Baby” in country. By the mid-’70s Newbury had moved to Oregon. While he continued to release critically acclaimed albums, the albums were never commercially successful, which seemed unimportant to him. As Sam Baker writes, “Mickey was pretty clear about his art. He wasn’t afraid to do what he believed his art should be … Mickey had an internal calibration that said, ‘I will not rest until this is the way I want it.’ He got the songs the way he wanted them.” Bobby Bare recalls that “Mickey could sing the alphabet and make you like it … Mickey should have been a monumental [success], but he was his own worst enemy … He wouldn’t compromise and do what somebody else wanted.”

Although Waylon Jennings’ “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)” dropped Newbury’s name (“Newbury’s train songs”), he never gained the fame Jennings or Nelson or Kristofferson did. In an interview from 2018, the Muscle Shoals songwriter Donnie Fritts told Atkinson: “Why Mickey isn’t better known is a damn good question. I can name a bunch of people I thought were gonna be biggest stars, but they weren’t for whatever reason. They did well but didn’t do nowhere near what you thought. I don’t know it was Mikey holding himself back by not playing the game.”

Songwriter Chris Gantry told Atkinson, “Mickey [eventually became] disillusioned with the business. He was evolving in his own little wild head and didn’t relate to the music in Nashville. He was never a guy who put his footprint into anything too long before it dried up … There was only one Mickey Newbury musically … His presence got scarcer and scarcer even though he was producing a lot of music. Mickey didn’t care about fame. He cared about strange things in his head and how he approached songs … He loved making the music, and he loved to disappear.”

Rodney Crowell recalls Newbury’s influence on him: “Mickey was a rare dude. He was dazzling one on one, but taking it out to a bigger scale wasn’t his nature … if people would bother to look at songs like literature in a hundred years, ‘Cortelia Clark,’ ‘San Francisco Mabel Joy,’ and ‘Heaven Help the Child’ have to be alongside the great narrative songs like [Guy Clark’s] ‘Let Him Roll,’ [Van Zandt’s] ‘Pancho and Lefty,’ and [Marty Robbins’] ‘El Paso.’ How much better can characters be profiled in a song?”

Gretchen Peters, whose 2019 album The Night You Wrote That Song: The Songs of Mickey Newbury honors Newbury’s work, says: “I think Mickey’s in the top three purely genius songwriters in country music history … Mickey’s melodies are gorgeous, but his lyrics are devastating. He could take a song from sad to devastating simply by the power of his lyric writing, he’s one of the very best we have. A great country song has very simple straightforward lyrics with no trickery … Country is simple and honest, so the choice of words is hugely important.” (Read Peters’ 2020 essay for No Depression on Mickey Newbury.)

These are only a few voices raised in tribute to Newbury and the legacy of his writing. Atkinson collects interviews from over several years for the book, and they range widely from those who never met Newbury but who’ve been deeply shaped by his songwriting — such as Will Oldham and Charlie Worsham — to those, like Charlie McCoy and Billy Swan, who knew him and worked with him. Looks Like Rain: The Songwriting Legacy of Mickey Newbury is the perfect introduction to Newbury’s life and music, and sends us again, or for the first time, to listen to Newbury’s albums.