THE READING ROOM: Biography Peers at the Man Behind Guitar God Clapton

Sometime in late 1965 or early 1966, a slogan spray-painted on a wall in London proclaimed: “Clapton is God.” Although he later said he was embarrassed by the slogan, Clapton’s fluid guitar riffs across a range of styles revealed his ceaseless efforts to become the world’s greatest guitarist. Even if he was never satisfied with his playing, his fans certainly raised him to the status of a deity, worshipping every elision that moved a blues tune into a scalding rocker (“Blues Power”), every riff that became like the line of a repeated prayer (“Layla”), and every concert that became an occasion to worship at Clapton’s altar. Because Clapton remained mostly out of the public eye — except for the concerts — he also had an air of mystery about him and rumors circulated about him. But when a new Clapton album hit the shelves, his adoring fans flocked to the stores so they could purchase another relic from the god they worshipped.

Because Clapton let his fingers guide him where they would, his albums were uneven and sometimes disappointing: His first solo album, Eric Clapton (1970), featured the arpeggios of “Let It Rain,” the propulsive “Blues Power,” and the rocking version of J.J. Cale’s “After Midnight.” Later that same year, Clapton put together Derek and the Dominoes, a kind of supergroup (Bobby Whitlock, Carl Radle, Jim Gordon, Albhy Galuten, Duane Allman), and released Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs. While the album featured a few covers — “Key to the Highway,” “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” “Have You Ever Loved a Woman?” “Little Wing” — most of the album features songs written by Clapton or co-written by Clapton and another of the Dominoes, often Bobby Whitlock. Four years later, Clapton released 461 Ocean Boulevard, which featured Clapton’s take on Bob Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff” but was otherwise unmemorable. The albums that followed all had their moments, and fans were always surprised, or disappointed, with the new music, but they could always depend on Clapton to scrawl his own electrifying signature on the songs.

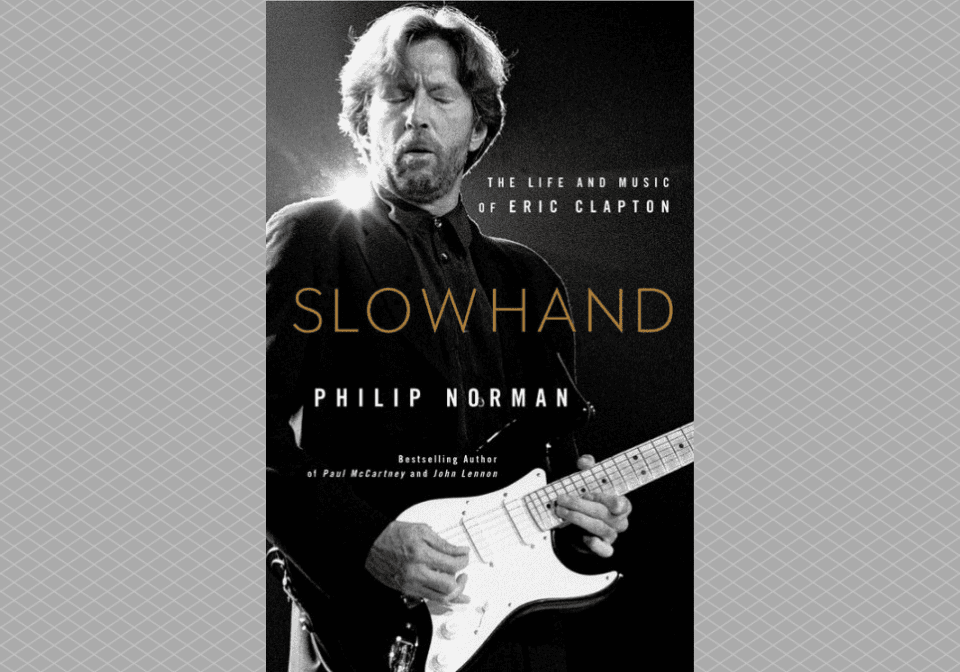

In 2007, Clapton told his own story in the sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll-drenched Clapton: The Autobiography (Crown Archetype), so it’s a little puzzling why Philip Norman’s Slowhand: The Life and Music of Eric Clapton (Little, Brown) appeared late last year. Norman has already written sturdy and reliable biographies of Paul McCartney, John Lennon, and Elton John, and as he cast about for a new subject, he settled on Clapton. He reveals very little new about Clapton in this workmanlike biography, though he faithfully chronicles Clapton’s childhood and his rise to fame. In a conversation with Clapton’s former wife Pattie Boyd, Norman reveals, for example, Clapton’s particular neediness. When he’s about seven or eight, Clapton learns that his mother and father have handed him over to his grandmother, Rose, and uncle, Adrian, to be raised as their own. As Boyd tells Norman: “He became the wounded child. From then on, everybody around him seemed to feel the obligation to take care of him and prop him up … his family … then managers … other musicians, like Pete Townshend. … There was always someone to shield him from anything unpleasant, like taking a driving test or getting rid of a musician in the band he didn’t like. … He never hit the ground, never grazed his knees, never bumped into life.”

Clapton emerges as a sensitive, sometimes reclusive musician who seems never satisfied either with his own guitar playing or with the bands he leaves behind in a trail of unhappiness: the Yardbirds, John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, Blind Faith, and Cream. Norman reveals Clapton’s deep love of material things — fine cars and fine fashion — as well as his penchant (not unusual among guitarists) for naming his guitars. Norman draws on conversations, with Clapton’s full consent, with the guitarist’s friends, musical associates, and family members, though he has no new conversations with Clapton himself. Norman traces Clapton’s rise to fame from his early years in art school to his roles in various bands from Cream to Derek and the Dominoes, as well as his now-famous love affair with Boyd, his heroin and alcohol addiction, the death of his son, Conor, and his organizing the Crossroads guitar festivals starting in 2004.

One of the most memorable moments in the book occurs when Clapton meets Aretha Franklin, in a meeting engineered by Atlantic Records head Ahmet Ertegun. Franklin was working on her album Lady Soul when Ertegun walked into the Atlantic studios in New York City. He had asked Clapton to lay down some guitar parts on Franklin’s “Good to Me as I Am to You. “He found the famously temperamental and insecure Franklin with her clergyman father and sisters, and a crowd of top session guitarists among whom he recognized the brilliant Joe South, Jimmy Johnson, and Bobby Womack. Ertegun dismissed them all and sent him in alone. Aretha was at the piano, Ertegun would recall. ‘When Eric walked in with his Afro hair and pink trousers, she started to laugh. But as soon as he played, Aretha stopped laughing.’”

Why do we need a biography of Clapton, especially when he’s told his own story in detail? What does Norman add that we don’t already have? Well, Norman offers very little but a fan’s note and some distance and perspective. For readers who haven’t read Clapton’s autobiography or seen the documentary about him called Life in 12 Bars, Norman’s biography is a good enough place to start. Readers familiar with the other sources, though, can likely skip Norman unless they want an outsider’s perspective on their subject.

Even so, Norman offers some sobering reflections on which most every Clapton fan is likely to agree.

“Clapton writes songs, but without the fecundity of a McCartney or a Dylan; he sings, but always seemingly a bit under sufferance; as a performer, he has none of the flamboyance or daring of a Bowie or a Jackson. Such things are of no account when set against his single, immense gift, the ability to conjure magic from a slab of electrified wood. Over the years, he has seemed less like a god than some mythic gunfighter or pool-player whim young upstarts are constantly challenging, only to retire defeated like everyone else (bar Hendrix). He’s the guitar’s Wyatt Earp or Minnesota Fats, peerless not only in rock but in the blues, a form which for generations was supposedly the preserve of poor black troubadours bewailing the hardship and oppression of their lives…It is not merely a question of fast fingers nor even a unique ‘sound,’ for Clapton has created so many across a spectrum from heavy metal to reggae … his mastery can touch the sublime, as if it comes from somewhere outside his so ordinary-seeming self.”