THE READING ROOM: ‘Black Country Music’ Centers Stories of Fans and Artists of Color

Many country songs evoke the persistent longing for place, for community, for belonging, but in many of those songs inclusion comes only through the exclusion of others. Although there are exceptions, country music has long excluded women, queers, and Black and Brown artists from the country mainstream in order to close the ranks of the grand old tradition of country music.

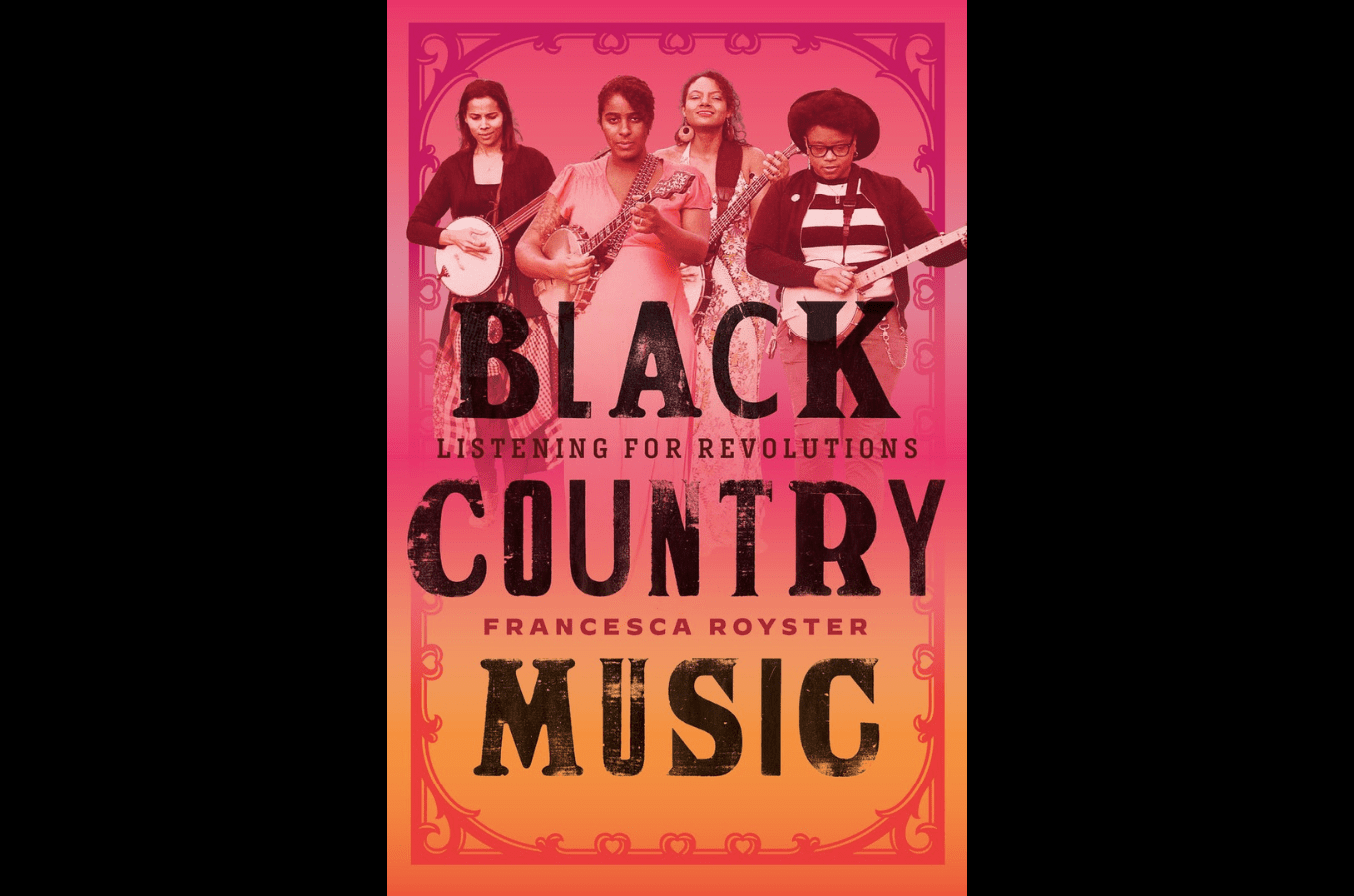

While Marissa R. Moss’ thought-provoking Her Country: How the Women of Country Music Became the Success They Were Never Supposed to Be (Holt) (ND review) explores the ways that mainstream country often excludes women artists in the name of inclusion, Francesca Royster’s compelling Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions (Texas) examines the complex layers of race and otherness in country music. Royster’s book cannily combines memoir — she tells her own stories of loving country music and trying to discover her place as a Black queer woman who’s a fan — and critical analysis of Black country artists and their music and how they are negotiating the territory of country music and making their place within it.

Royster opens her book by sharing her experience at the 2014 Windy City Smokeout, a country music and barbecue festival in Chicago. When she tried to ask Black festivalgoers about why they were there and why they liked country music, they responded by telling her they were just there for the barbecue. She reveals that she was asking these same questions of herself back then, but she also recalls that she was “growing to love Black and Brown country music’s ability to capture different and complex stories in their lyrics and sounds, sometimes by hiding in plain sight. I found myself drawn to the resourceful stories of making do and sometimes failing, like the Black and Brown sounds of country-soul crooner Freddy Fender’s ‘Before the Next Teardrop Falls.’”

At the same time, Royster expresses the challenges of being a Black country music fan: “Being a Black country music fan can feel lonely and sometimes dangerous. It sometimes feels unsafe to listen to such personal, vulnerable music in public space not of our own creation. Perhaps this is why, until recently, the African American presence in country has been more or less ‘hidden in the mix,’ as [music scholar] Diane Pecknold puts it, with Black country performers being treated like the exception to the rule.”

Despite this, she points out that “for many artists, Black and country go together naturally.” She observes that writer Alice Randall’s suggestion that the “connection between country music and Black culture is both ‘natural’ and ‘healing’ is nothing less than revolutionary, challenging the dominant thinking that country music is inherently a white cultural form that should be protected from the corrupting force of racial, cultural, and generic mixing.” Black people, she writes, “are always inventing new ways to survive the unfreedoms of white supremacy, and this includes country music.”

Royster, a professor of English at DePaul University in Chicago, declares in her study that putting “Black artists and fans at the center of this inquiry is to irrevocably shift country music as a genre. It forces us to remember, reengage, and hopefully transform country music’s racial past.”

At the center of Royster’s book are her analyses of artists including Tina Turner, Darius Rucker, Beyoncé, Valerie June, Our Native Daughters (Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, Allison Russell), Mickey Guyton, and Rissi Palmer. She questions, for example, why artists such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and others are often celebrated for being outlaws but Black women and white women are marginalized for challenging authority (for example, Beyoncé performing her song “Daddy Lessons” with the Chicks at the 2016 CMA Awards. “Country music has made room for its white male country outlaws,” Royster writes, “even if it doesn’t always make room for outspoken Black women.”

Valerie June embodies generations of the Black experience in her voice and her music. The ghosts of the past haunt her songs and her vocals, according to Royster. “Valerie June is a ghost catcher,” Royster observes. “She takes on the elements of risk and tenderness in her work, honoring moments of mortality and struggle in the music she admires and giving it back to us, with her own spin — whether it’s her version of Jimi Hendrix’s tender ‘Little Wing’ or her own ‘Shotgun’ — to create something new that honors the past … In Valerie Jean’s music, I see a powerful example of African diasporic music’s ability to hold culture in the body and voice … in her embrace of her voice’s ‘past imperfections,’ recalling the styles of lesser-known Black female country artists of the past, such as Jessie Mae Hemphill and Elizabeth Cotten, among others, June also makes use of it to call up ‘spirits,’ to conjure the ancestors.”

Black Country Music is an exhilarating book, and Royster’s ingenious blend of memoir and analysis showcases the emerging artists and fans that she affirms are “changing what country music looks and sounds like.”