THE READING ROOM: Book Hangs Onto Disappearing History of Music Row

For many, Nashville means the bars owned by the stars — Blake Shelton’s Ole Red or Alan Jackson’s AJ’s Good Time Bar — or the legendary Tootsie’s, the honky-tonk across the alley from the Ryman Auditorium into which Opry stars would slip for a quick shot between shows. For others, Nashville means the Gaylord Opryland Resort and Convention Center, which since 1974 has been home to the Opry House and the Grand Ole Opry.

For still others, especially those who dream of a life in music, Nashville means Music Row, a small section of town located between 16th and 17th Avenues South (Music Square East and Music Square West, respectively). Numerous songs evoke the almost mystical atmosphere of this cluster of music publishing houses and recording studios where dreams are made or broken. While Marty Stuart’s “Sundown in Nashville” sings of those broken dreams at 16th and Broadway being swept out of town at sundown, the most famous is Larry Cordle’s and Larry Shell’s 1999 “Murder on Music Row” — made popular by the Alan Jackson-George Strait version of the song — which captures the disappearance of country music from Music Row:

Oh, the steel guitars no longer cry and you can’t hear fiddles play

With drums and rock ‘n roll guitars mixed right up in your face

Why, the Hag, he wouldn’t have a chance on today’s radio

Since they committed murder down on Music Row

Why, they even tell the Possum to pack up and go back home

There’s been an awful murder down on Music Row.

As any longtime Nashvillian will tell you, Music Row is now a shadow of its former self. A parking deck now stands just off Demonbreun Street on the site where Hank Williams is rumored to have lived early in his career. Bobby’s Idle Hour Tavern, on 16th Avenue South, where novices and professionals gathered to play new material, closed in 2019 to make way for a high rise. A new high-rise hotel sits on the site of Mack’s Café on Division Street, where one musician remembers walking in “around 2 a.m. and Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings were sitting with Emmylou Harris in the corner … feeding the jukebox.”

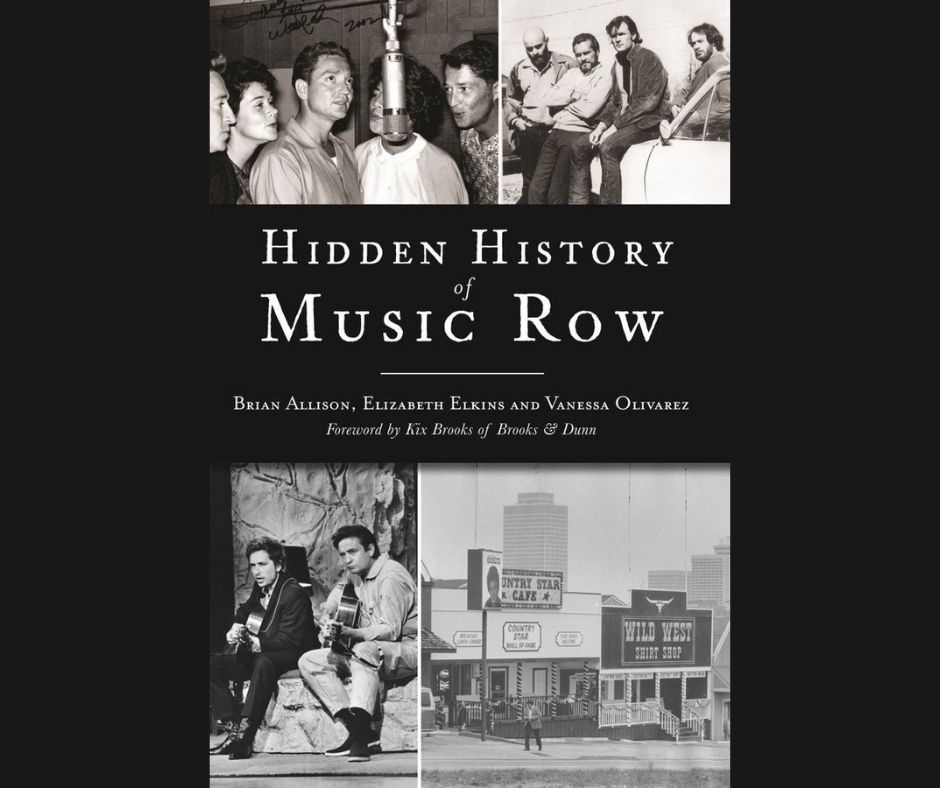

With so much history being paved over, it’s nice to have something to remember it by via Hidden History of Music Row (The History Press), by Brian Allison, Elizabeth Elkins, and Vanessa Olivarez. Elkins and Olivarez are Granville Automatic, whose new album, Tiny Televisions — released to coincide with the book’s release — was inspired by the stories in the book. Historian, museum consultant, and writer Allison grew up listening to stories of country music; his father, Joe, was a producer, songwriter, and radio personality (Joe and Audrey Allison wrote Jim Reeves’ 1960 hit “He’ll Have to Go”).

In this fascinating book, the authors alternate telling illuminating stories of the people, places, songs, and events that reveal some little-known facets of Music Row. Scores of never-before-seen photos illustrate the stories in the book.

“Getting the opportunity to write a book was a real surprise for us as a band,” Elkins explains. “An editor at the History Press found us through an article in The Bitter Southerner about our last album, Radio Hymns. That record was all about Nashville’s lost history and he felt it would be interesting for two songwriters with a love of history to team up with a historian and tell the stories of this extraordinarily complicated, mysterious, and mythical place, warts and all.”

“Music Row is as complicated as the musical myths that surround it, both in terms of geography and history,” they write. They define Music Row as “the arrow-shaped neighborhood stretching from Wedgewood Avenue and Belmont University on the southside, to Broadway and Interstate 40 on the north, with Villa Place as an eastern boundary and Broadway or 18th Avenue as a western one, excluding the intrusion of Vanderbilt University.” In this little “arrow-shaped neighborhood,” outlaws made a record, a naked woman strolled the streets in an attempt to get a studio to notice her, churches stood next to publishing houses, and Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and Neil Young recorded albums in various studios.

Many who have driven into Nashville off the interstate have been startled to see the exit for a street with as malevolent-sounding a name as Demonbreun. In many ways it’s the gateway into the city, and it’s certainly the gateway onto Music Row, since you travel down that street to get to 16th and 17th Avenues. Elkins opens the book with the story of Timothy Demonbreun, a fur trader who lived in a cave outside the city but bought up lots in the city, though his intentions for that land, as she points out, faded as the city developed. “Demonbreun Street traverses what was once a part of his property,” Elkins writes, but the “street’s namesake was a cheater, a drinker, a fist-fighter, an adventurer, and a European-style Romantic caught up in the dusty spirit of a new frontier … he was an anti-hero at the heart of thousands of country songs that would later be written on his land.”

For Olivarez’s chapter on Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson, Jessi Colter Young, and the Outlaws, she interviews Chris Gantry, one of the last remaining leaders in the movement. He recalls the Tally Ho Tavern (formerly located near the current site of Curb Records on 16th Avenue) as a “Hillbilly archangel hangout. It was like all the people who were crazy in the world that loved country music — lived for it, died for it, breathed it, and had been doing it for years, ended up there about 3:30 in the afternoon. … For a young songwriter, it was like being in a Shakespeare class. You heard the real vernacular of country people, put into story songs that were indicative of rural life and hardships on the road, hardships in marriage, love affairs, the beauty of alcoholism, the beauty of the road, the hardships of the Bible Belt and trying to live up to the word of God, and being crazy, and carrying a gun, and fighting with grandmothers who drove you out of the house with shotguns.”

In a chapter on the changes on Music Row in the ’90s, songwriter Tony Martin recalls that “in the ’90s, you could pop into publishers’ offices and demo sessions though. It was a free-flow creative thing where you mixed and hung out and talked. The writing started at 9:00 a.m. … we broke and had lunch at places like the Tavern on the Row, the LongHorn Steakhouse or Maude’s — I called them all the “Music City Cafeteria” — and you saw other people and artists who were writing that day. Think of all the writers as molecules bumping into each other and creating friction — you wrote, talked about life, went to lunch, wrote more. … You wanted to be on the Row.”

Hidden History of Music Row is a must-read for anyone who loves country music and its history, who wants to hear some rollicking good tales from the mouths of those who lived them, and who wants to discover more details about a town they love. It’s chock-full of entertaining stories about the denizens and the dwellings of a section of Nashville that is too quickly being buried under real estate developers’ bulldozers. In that sense, the book uncovers hidden history as a means of encouraging us to preserve the history we still have standing on Music Row.