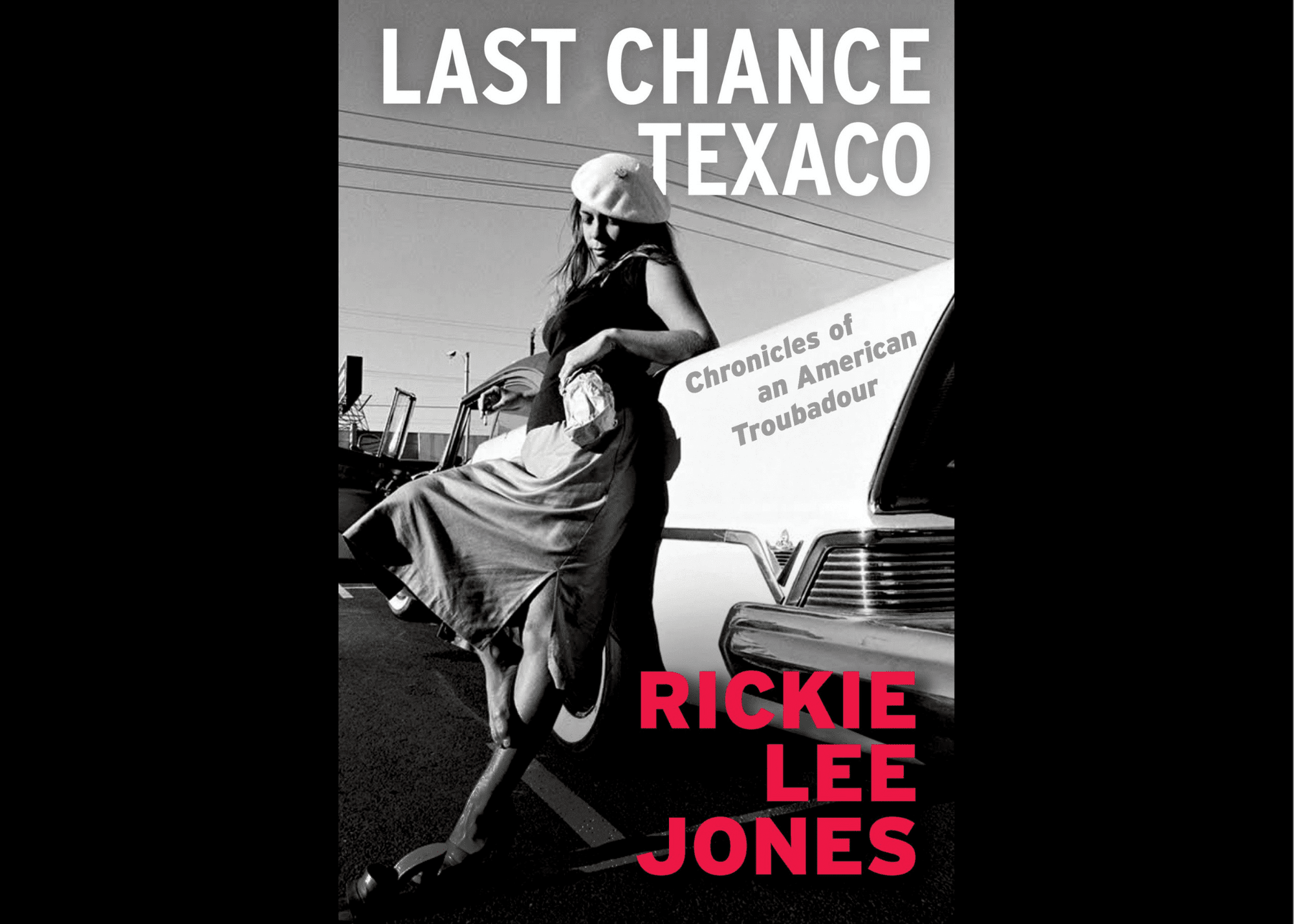

THE READING ROOM: Buckle Up for the Ride in Rickie Lee Jones’ Memoir

All her life Rickie Lee Jones has been looking for that beacon that lights up the sky to show her the direction to travel next. Running down a highway, following the music or destiny that carries her forward, Jones moves peripatetically through the hills and valleys of broken relationships, stuttering family life, and the magic of the music that heals her. Jones tells her stories for the first time in her riveting, often harrowing, memoir Last Chance Texaco: Chronicles of an American Troubadour (Grove). In staccato prose that echoes her scat singing, Jones holds nothing back as she chronicles her adventures on the road and the ragged ups and downs of her family life and fame.

With the free-flowing sonic patterns of jazz, Jones’ memoir swirls across time, moving backward and forward with reckless abandon, hardly pausing as the breathlessness of her journey overtakes us (and her). From the memoir’s opening pages, Jones is always on the move —driving, driving, driving, either with someone or alone. “When I was twenty-three years old I drove around L.A. with Tom Waits. We’d cruise along Highway 1 in his new 1963 Thunderbird. With my blonde hair flying out the window and both of us sweating in the summer sun, the alcohol seeped from our pores and the sex smell still soaked our clothes and our hair.” After she and Waits suddenly stop seeing each other, she’s riding around with Lowell George; when he leaves, she writes, “I drove around alone for the rest of the year.”

Jones spends most of her life in “cars, vans, and buses. Back seats, shotgun and driving myself.” As she writes: “From these vantage points I watched life approach and recede. As time went by I was always running away from and moving to a new life, but once I got here I could never lay down roots. For me, it seems like life is the vehicle and not the destination.”

The singer-songwriter is on the move, though, as early as she can remember. Born in Chicago in 1954, she and her family hit the road when Jones was just four, moving to Phoenix, Arizona: “My family took such a long trip across America that I felt as if I had always lived in the back seat of our 1959 Pontiac.” Once they had landed in Phoenix, Jones’ parents both worked multiple jobs, trying to provide something like a normal life for Jones and her brother, but underneath the veneer of normalcy lay boiling springs of tension that eventually scalded the bonds of her parents’ marriage, leaving Jones to strike out often on her own.

One summer when she’s a teenager, Jones is living with her father and working at his steakhouse; she’s banking her own money in the account he’s opened for her. On an afternoon off from her job, Jones is hanging out on her front stoop with some boys from the townhouse a few steps away when her father calls her inside. Before she can close the door behind her, her father starts hitting her with his open hand, demanding to know what she’s doing. Humiliated and hurt — “Oh, why couldn’t my life just go right for a minute? For so many years, disaster after disaster and chaos on top of chaos was my normal.” — she runs up to her bedroom, where she puts on Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland and loses herself in music. “Musicians opened the door to imaginary places, to better realities, and Jimi’s music was the place I belonged.” In that moment she decides to run away to Northridge, California, to a rock festival.

Once she’s at the festival, her adventures begin as she catches a ride after the festival with some “heads” to San Diego, where she discovers the music of Crosby, Stills & Nash. “The tide that followed CSN,” she writes, “was a decade of gentlemen poets and canyon ladies who were either tough broads or whimsical fairies … The 1970s were a prehistoric gene pool of musical possibilities. Music replicated and bore strange new cells. The virus of a new idea had taken hold and changed who we had been.”

By the end of the ’70s, Jones finds her own way into this troubadour gene pool with her eponymous first album and the hit “Chuck E’s in Love.” Though her music climbs the charts and she even appears on Saturday Night Live, she reflects: “I can tell you that fame brings no solace, no love, and no warmth. I can tell you also that money isolates … Fame is a tincture made for the brightest and deepest souls among us. We have what it takes to withstand it. Fame was never meant for the fifteen-minute brand. This troubadour life is only for the fiercest hearts, only for those vessels that can be broken to smithereens and still keep beating out the rhythm for a new song.”

In the end, Jones writes, “Music shapes us and fundamentally changes us. Once we have listened we do not stop. We do not ever recover from music. We will return again and again to the radio, to the record store, the bedroom where girls listen to records all day.”

Last Chance Texaco carries us on one hell of a road trip, never stopping for gas, and often leaving us gasping as we try to keep up. In the driver’s seat all the way, Jones careens around some nerve-wracking hairpin turns, flies down some straightaways, walks away from a few crashes, and emerges with a tale about the power of music to heal and inspire and sustain.