THE READING ROOM: Christgau Collection Shows How Music Is Still Good to Ya

Not everybody agrees with the Robert Christgau, the Dean of American Rock Critics, when he dispenses his criticism of a new album or an artist’s body of work. He can be cantankerous and come across as arrogant, but you can never put down one of his reviews, essays, or columns without having been moved in some way or another by his in-depth involvement with the music itself.

Here’s a critic who’s deep in it, who lets the music find him and lets it move in him and then artfully tells us why we will want to, or not want to, listen to this album, or pay attention to that artist. He’s so much like that other great cultural critic, Susan Sontag, who challenged us in her elegant essays to look deeply into artistic styles, new genres, and unfamiliar books, art, and film. Sontag often declaimed from a perch of authority that she had well earned, and that could be frustrating and maddening, as if she were telling us that hers was the only view. Once we got inside her essays, though, her writing carried us beneath that veneer of defiance — though in some ways she never let her guard down — to see the marvels or the inanities or absurdities in a film or a novel or a cultural style that she wanted us to see. Sontag’s brilliance, and the beauty of her writing, grew out of her intimacy with the works she shared with us, and Christgau’s brilliance, and the elegance of his writing, grows out of a similar intimacy.

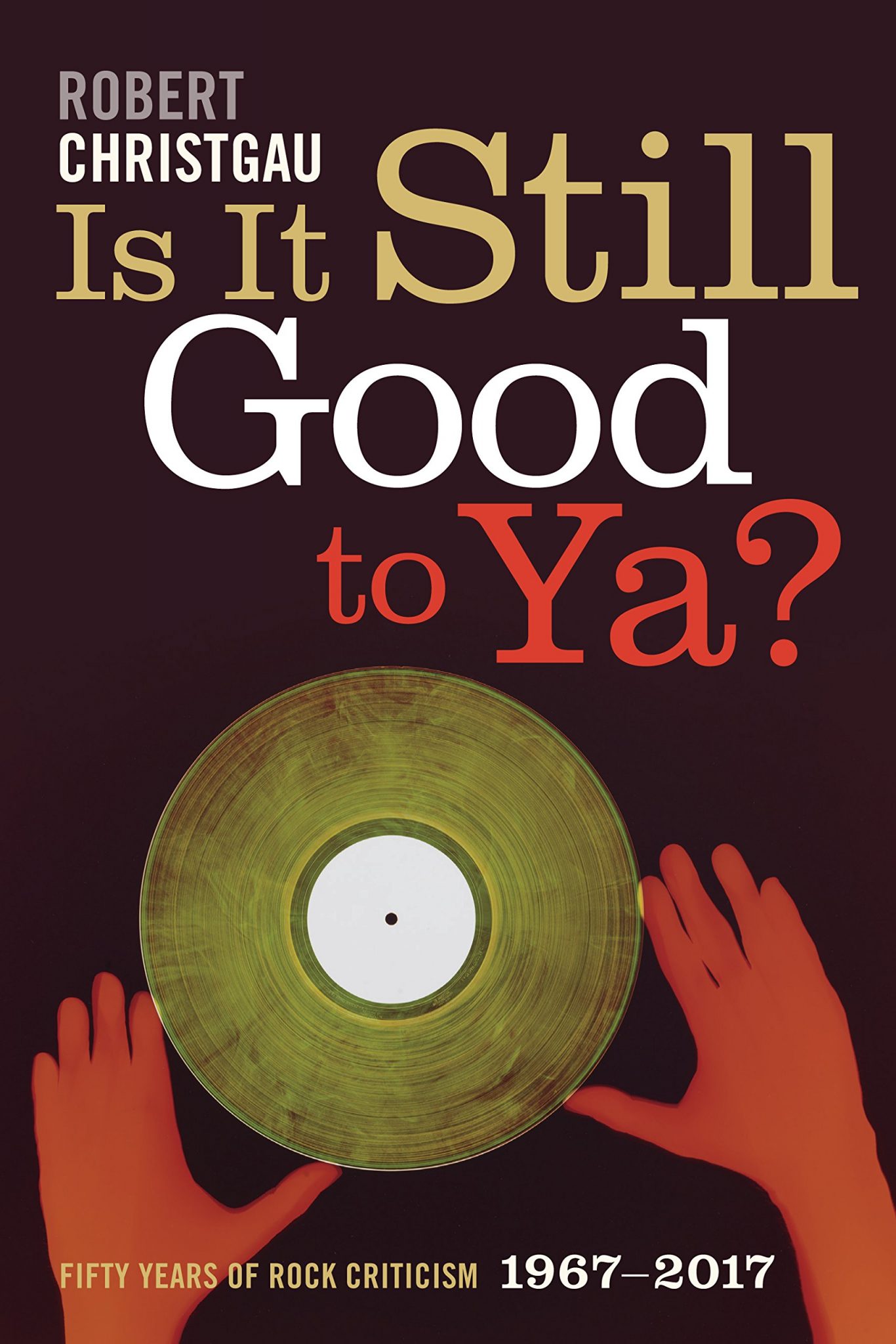

We have yet another opportunity to read a selection of his essays, reviews, and even a few obituaries in his new collection, Is It Still Good to Ya?: Fifty Years of Rock Criticism, 1967-2017, which includes pieces published in the Village Voice, the Barnes and Noble Review, Noisey, and a few other places. The titles of the sections describe illustrate the broad sweep of the pieces in the collection: “History in the Making” ranges over topics from classic rock and “postclassic disco” to Woodstock ’94 and Harry Smith’s Anthology of Folk Music; “A Great Tradition” moves widely over artists as diverse as Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk, and Chuck Berry, ‘N Sync, Willie Nelson, and the Holy Modal Rounders; “Millennium” casts its glance over “Music from a Desert Storm,” the Moldy Peaches, and Steve Earle; “From Which All Blessings Flow” glances at spirituality in music; “Postmodern Times” ranges over albums by everyone from Kanye West and R. Kelly to Sonic Youth and Miranda Lambert; “Got to be Driftin’ Along” features obituaries of David Bowie, Prince, and Ornette Coleman.

Some of the best pieces in Is It Still Good to Ya? are the most autobiographical ones in which Christgau reflects on the ways he listens and on the pleasure that music gives him, as well as the ways that pleasure is inextricably tied, for him, to meaning. “For rock critics, pleasure is where meaning begins. A tune you hum in your head so your mind can hear it again, a beat that motorvates your body even where the main thing moving is your pulse, the slight flush that radiates from the mandible toward the ears at the right lick or turn of phrase, the virtual chuckle of amusement or amazement as that moment comes by again. Given our word rates, why else would we do the job? … If pleasure is where meaning begins, what this pleasure means is inextricable from the unease that comes with it.”

When people ask him what he listens for in music, he responds candidly: “Maybe some other kind of critic could offer answers. Maybe someone trained in sonata-allegro procedure has the discipline to ignore transient pleasures and proceed immediately to structure. Maybe someone who reads music can establish stringent criteria of melodic originality. … But like most pop fans, I don’t have such fancy equipment at my command. So I don’t listen for anything. I just try to make sure that music I like finds me. … More often, I wait until I catch myself reacting to a newly imprinted snatch of melody, moving my body or mind to a groove, enjoying a funny rhyme or pithy turn of phrase, humming along, lying in bed with a song I can’t pin down ringing in my head.”

His two pieces on Aretha Franklin, written five years apart, are two of the best in the book. When Aretha is on, he writes, “what defines her magic is that she’s in the music but not of it. All her great performances, even ‘Who’s Zoomin’ Who?’ and ‘Freeway to Love,’ are infused with suffering, and from ‘Ain’t No Way’ to ‘In the Morning,’ all her suffering is infused with joy. … The reality Franklin accesses is spiritual, philosophical, metaphysical — the essence of pleasure in all its incomprehensible immediacy. There’s pain in there, can’t live without it. But that’s for completeness’s sake. Like a rose, which when it pricks is still a rose. And so damn happy about it.”

Like most collections, Is It Still Good to Ya? is uneven, but most of the pieces overflow with Christgau’s passion, his incisive wit, his steely gaze, his unwavering devotion to the grooves of popular music, and his always stimulating prose. Every piece here contains quotable material, so readers can turn to any piece and be enriched by it. As he reminds us early in the collection: “Music that’s good to ya will by just that token also be good for you.” Christgau’s writing is still good to us and for us.

UPDATE: The National Book Critics Circle Board of Directors has named Robert Christgau’s Is It Still Good to Ya? one of its five 2018 finalists in criticism.