THE READING ROOM: Dave Marsh Collection Offers Rock Writing With a Heart

According to at least one former music magazine editor’s recent collection of interviews and public conversations, rock and roll is the province of aging white men. Jann Wenner even titles his collection The Masters, as if the seven artists on which he focuses — Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Mick Jagger, Pete Townshend, Jerry Garcia, Bono, and Bruce Springsteen — were the plantation owners and women artists and Black artists merely fieldworkers and domestics. To be sure, Wenner put together his simpering collection with his friendship with these seven artists — and with a very clear and narrow definition of rock and roll — firmly in mind. It’s the worst kind of rock and roll book, but it’s also what we’ve often come to expect from early rock journalists and critics looking back on their halcyon days.

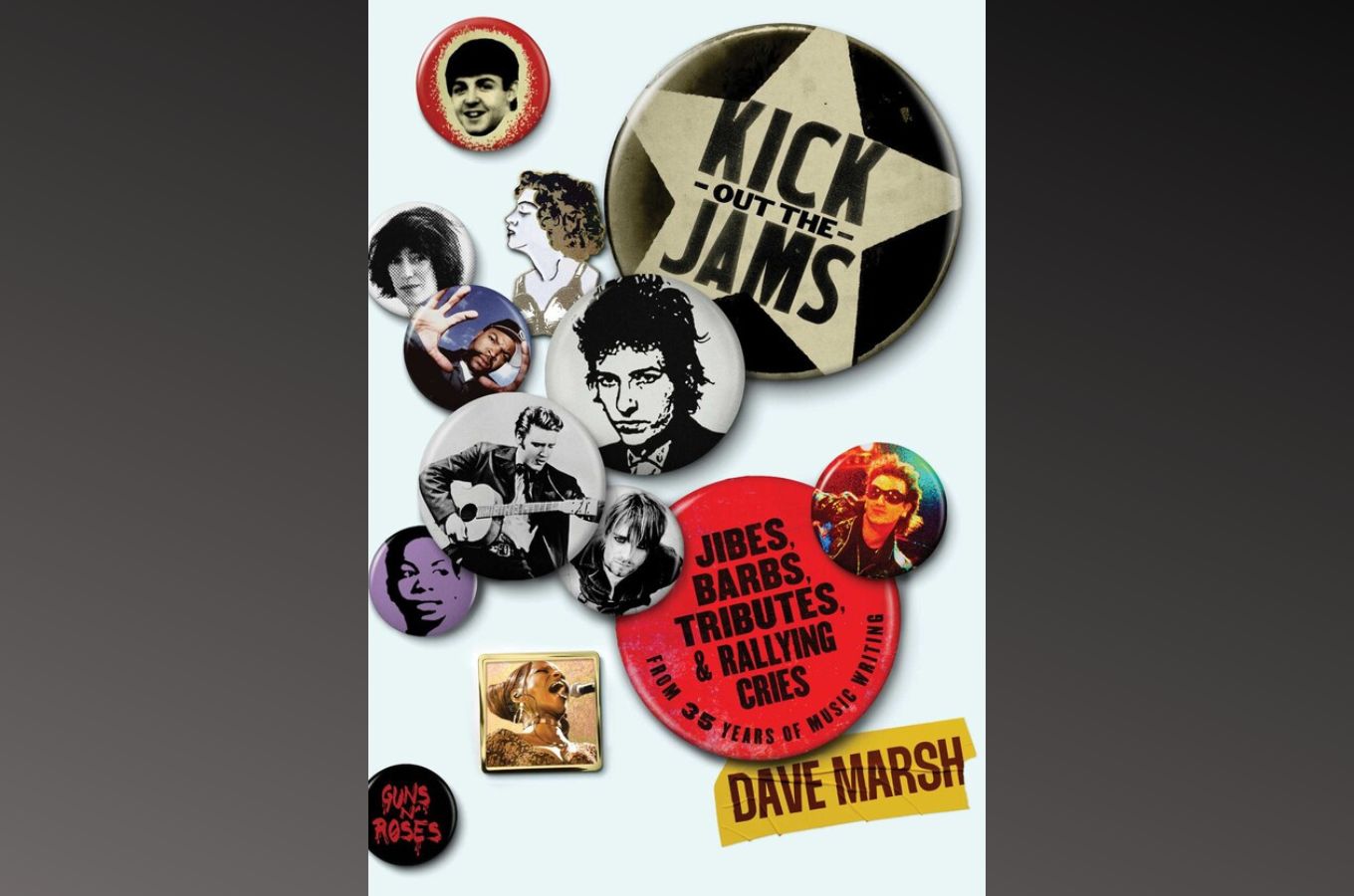

Thank goodness, then, for Dave Marsh, whose extensive writing about rock and roll reflects his restless search for the soul of the music, his refreshing candor in calling out musical imposters, and his deeply emotional connection to the music and artists about whom he writes. Marsh was one of the first editors at Creem — in its day a more down-to-the-bone rock magazine than Rolling Stone — and wrote for Rolling Stone and several other publications. In 1982, he co-founded the newsletter Rock & Roll Confidential — renamed Rock & Rap Confidential. He’s written more than 22 books, with his first commercial success coming with the publication of his 1979 biography of Springsteen, Born to Run: The Bruce Springsteen Story. In 1985, Marsh published a collection of his music journalism, Fortunate Son, and his new book, Kick Out the Jams: Jibes, Barbs, Tributes, and Rallying Cries from 35 Years of Music Writing, edited by Daniel Wolff and Danny Alexander, is his second collection of such writings, picking up where Fortunate Son left off. Thus, the pieces in this collection range from 1984 to 2017.

The beauty of Marsh’s writing lies in its emotional openness and honesty. In music writer Lauren Onkey’s splendid introduction to the collection, she writes that Marsh “can be so heart-on-his-sleeve emotional about rock and roll.” Indeed, Marsh’s collection resonates at such a deeper well of feeling than most other music critics’ collections because he’s deeply invested himself in the music and in offering others a way into it. No insider language or backstage nods here; rather, it’s a clear-eyed — and sometimes teary-eyed — reflection on how the music touches (or in some cases repels) him. In an introduction to the collected pieces from the 2000s, for example, Marsh levels with his readers about what he’s trying to do in his writing: “If you just tell everybody what’s serious, first you’re going to bore people. Secondly, people are definitely not going to know what you’re talking about half the time. You were going to be forced — because this is America; maybe it’s the world — to be sober. Don’t smile. And the music I loved wasn’t like that. The girls I loved, the people I loved, thought the whole shebang was as fucked up as I did. And that it was funny.”

In a piece from 1993, Marsh reflects on the challenges of being a music critic: “For a musical omnivore like myself, the job is truly impossible. The time I spend trying to figure out dancehall is insufficient, my take on grunge too affected by my age and history, there were probably six or eight fine country voices that got by me while that fascinating but as yet undeciphered cumbia anthology was playing, and I never heard Springsteen’s Unplugged LP … Confronted by all this, I can only tell you that listening to everything is still the right way to go … in the end, what you do tell people will add some perspective to what they’re hearing and maybe even help keep the historical record straight. That’s my version of the job, and I’m sticking to it for as long as I can make it last.”

All the pieces collected here illustrate the emotional depth of Marsh’s writing. On the televised Beatles Anthology, he wonders what value the show brings to viewers close to 30 years after the Beatles’ final break, and the answer, in part, is love: “Maybe the Beatles looked upon it and saw that it was good. Maybe they saw what I did, which is that it’s not only their music that holds up well, thirty years later, but also their legend — a story that deserves retelling because in it, we discover some valuable things about the way in which humans who do love one another can function creatively and prosperously.”

In a touching reminiscence of Bobby “Blue” Bland just after the singer’s death, Marsh captures that singer’s emotional center and why a song like “Members Only” brings tears to the eyes: “Bobby Bland was, in his prime, the most powerful blues shouter of all time, though capable as well of caressing tenderness,” he writes. “You know Bobby Bland’s name and music less well because he was like his audience: he was a key voice of the Black Southern working class from the ’50s onward. His role was to play the shouter from the anonymous ranks, the totally heartbroken man among an all-but-totally heartbroken folk. (And, of course, once in a while, shouting with exuberance all the greater because of that everyday heartbreak.)”

His witty zinger of a reflection on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame speaks to the ambivalence that many fans feel about the institution and its means of selecting new inductees: “For my part, I promise as a writer and broadcaster to continue to agitate for my friends Al [Kooper] and Wayne [Kramer] to be in the Hall of Fame. Whether they like it or not. After all, part of the fun of writing about rock ’n’ roll is that you get to contradict yourself, too. For instance, even though I play the role of nemesis among Deadheads, I think the Grateful Dead very much belong in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. After all, dopey though their music mostly is, they are very famous.”

In 1993, Marsh’s daughter succumbed to cancer. In the autumn of 1992, doctors discovered a sarcoma — “the rarest of rare cancers,” writes Marsh — in her abdomen. The most poignant piece in the entire collection is “Since I Lost My Baby,” which is both a eulogy for his daughter and a celebration of her life. Her death imbued Marsh’s writing thereafter. “I need to eulogize Kristen Ann Carr, because her death means I’ll never write about music in the same way. Not only because my family and I have gone through such a soul-shattering experience, but because Kristen helped me determine how I listened to music. From ‘Papa Don’t Preach’ and Seal’s ‘Crazy’ to House of Pain’s ‘Jump Around’ and Enya’s ‘Caribbean Blue,’ she made me hear stuff I might have dismissed. And I mean, she made me — she lectured me about it. In this way, she wasn’t my stepdaughter but a true child of my heart … That’s why the track on the tape I chose to speak for us was ‘Sweet Child O’ Mine.’ But another speaks for me alone: the morning after the funeral. ‘I’ve got sunshine on a cloudy day’ came over the radio and I lost it completely.”

The late Jimmy LaFave also suffered from a sarcoma, and Marsh got to know him during the time LaFave was going through the illness from which he eventually died. In the final piece collected here, Marsh offers a loving tribute to LaFave: “Listening to a really great singer — Smokey Robinson or Joe Strummer, Patty Griffin or Mary J. Blige — is to accept a unique sacrament. It may raise you high or smash you flat, but you’ll visit places you’ve barely imagined as well as those you know so intimately as to call home. Stopovers that confront you with your deepest fears, destinations driving your highest hopes. Jimmy LaFave is one of those singers.”

Kick Out the Jams offers an experience of rock and roll — and soul and rap and country and folk — that Wenner could never hope to give to fans. The music Marsh writes about matters deeply to him, and he knows how deeply music matters to fans whose lives it touches. Thank goodness for Dave Marsh, and thank goodness for this collection, which stands as one of this year’s books on rock and roll to be savored.

Kick Out the Jams: Jibes, Barbs, Tributes, and Rallying Cries from 35 Years of Music Writing, collected writings by Dave Marsh edited by Daniel Wolff and Danny Alexander, was published in August by Simon & Schuster.