THE READING ROOM: New Book Celebrates Street Singing Traditions

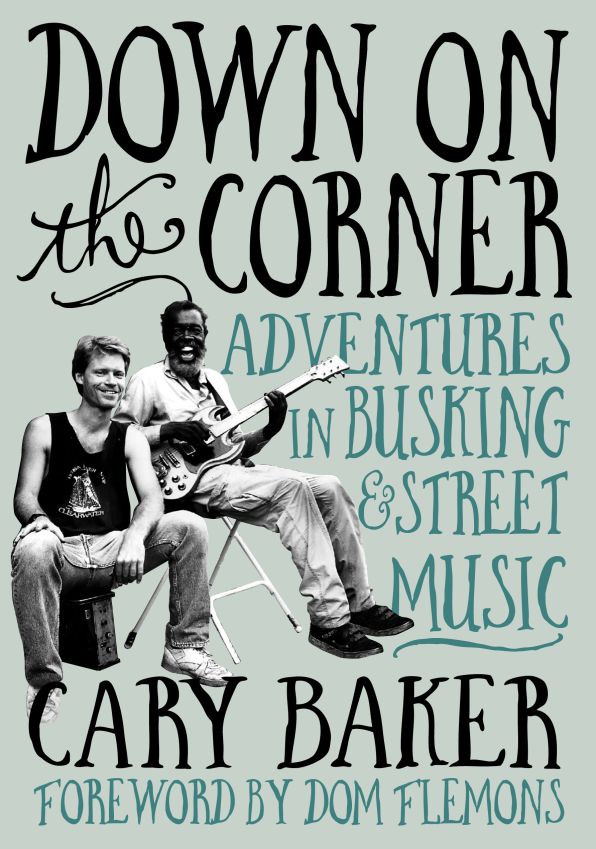

In 1969, Creedence Clearwater Revival celebrated the lives and music of a group of fictional street singers Willy and the Poor Boys in their hit song “Down on the Corner.” As the four boys gather on the corner near suppertime, there’s a “happy noise” as they try “to bring you up.” Each member of the little band takes a solo for a while, and they encourage the audience to “bring a nickel, tap your feet, and to lay your money down.” Fogerty’s lyrics capture the informality, joy, and community of street performance. Drawing his title from CCR’s song, writer and former public relations executive Cary Baker brings to life the art of busking in his new book, Down on the Corner: Adventures in Busking & Street Music (Jawbone Press, November 12, 2024).

In a series of vignettes that draw from numerous interviews, as well as his own encounters with street musicians in various cities over the years, Baker explores the wide range of musical styles that street performers play. Some of the buskers he includes—such as Lucinda Williams and Billy Bragg—moved from the streets to concert stages and record deals; others, such as British musician Tymon Dogg—who busked with Joe Strummer for five years before The Clash was formed—occasionally return to busking even after playing in world-renowned music venues. Still others, like Roger Ridley in Los Angeles, prefer that the streets remain their stage and entertain passersby and pull in a few nickels, because as Ridley says, “I’m in the joy business—I come out to bring joy to the people.”

After a brief—and somewhat garbled—introduction to the history of busking, Baker digs into the origins of street singing, including blues on Maxwell Street in Chicago and doo-wop on the corners of various cities in the Midwest and the East Coast. It’s on Maxwell Street where as a teenager Baker stumbled into his life-long love of busking, when his father took him to Maxwell Street Market, near downtown Chicago.

“The first thing I heard, long before I could see where it was coming from, was the sound of a slide guitar—not just any guitar but a National steel resonator guitar…We followed the music and found ourselves standing on the west side of Halsted Street, midway between Roosevelt and Maxwell, where Blind Arvella Gray was playing the folk/blues song ‘John Henry’—a song that seemed to have no beginning and no end,” Baker writes. “In that moment, I developed a lifelong affinity for the informality, spontaneity, and audience participation of busking.”

In the sections that follow, Baker conducts readers on a tour through the streets and subways and alleys on the east coast, in the South and Midwest, in California, and in Europe, introducing us to some familiar performers and some not-so-familiar ones and their stories of busking.

For example, the section on the east coast includes chapters on the Washington Square Park folk riot in 1961 (wherein police tried to enforce a ban on public singing in the park), Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Moondog, among others. New York City’s Washington Square Park, the open-air anchor of Greenwich Village, had long attracted musicians who met to play, sing, and trade songs. On Sunday afternoons, musicians would gather in small circles around the park, each playing different styles of music: bluegrass, old-time, folk. Those gatherings can’t be called busking in the sense that Baker uses the term here, since the musicians weren’t playing for money but only for the opportunity to play with fellow artists. In a few years, many of the artists from the park could be found in little clubs and basket houses—where baskets would be passed in order to collect money for the performers—around the village, playing for new audiences. These same artists, though, often returned to the park to their street singing roots.

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, now in his nineties, has done his share of busking. He and Woody Guthrie once “passed around the hat” as they were playing in Washington Square Park to scrape up enough money to pay for gas to go from New York to California. However, he doesn’t look back on his busking days with particular fondness: “I don’t particularly enjoy trying to sing out on some street corner hoping that somebody’s gonna give me twenty cents in a hat…There are romantics and there are incurable romantics. I’m a romantic, but I’m curable!” he told Baker.

Some buskers point out that their street singing days taught them enduring lessons about performing and songwriting. Tim Easton, who started busking when he lived in Europe in the 1990s, recalls that he took to street singing in part because all of his “heroes, like Jack Kerouac or Woody Guthrie or Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, were from the streets. They weren’t afraid to get right down in it and learn a thing or two about life and how to perform.” He goes on to observe that “busking was a mandatory thing for me because I needed to learn how to capture a crowd.”

While street singers can be found plying their trade on streets throughout the world, “it hasn’t remained low-tech: many of today’s musicians and performers use the internet to promote their act, but the tradition of performing on the streets for tips and donations remain constant,” Baker writes. “Some cities have even designated areas for street performers—New Orleans’ French Quarter or Austin’s East 6th Street, for instance—allowing them to entertain tourists and locals while preserving the character and culture of their city streets.”

Baker also includes the story of multimedia project Playing for Change, which produces albums and videos of street singers from around the world. Filmmaker and recording engineer Mark Johnson started the project with producer and philanthropist Whitney Kroenke Silverstein after he watched two monks playing music on a subway platform while on his way to the studio in New York City. The crowd that gathered to watch them was diverse, with homeless people standing next to businessmen, young people standing next to older adults. In that moment, Johnson had an epiphany and two things occurred to him: “One, when the music played, all the things that made these people different disappeared. And the second thing was that the best music I heard in my life was on the way to the studio, and not in the studio. And that was the beginning to Playing for Change—the idea of, Let’s bring the studio to the people,” he told Baker. “To me, you know, street music is one of the greatest art forms. It goes directly from people’s hearts—you can walk by and listen to this music, and it can change your day. And changing your day can change your life.”

Down on the Corner sings out the stories of these various buskers robustly, illustrating Cary Baker’s passion and appreciation for the art that happens out on the streets and fills the air with song and, if the musicians have a good evening, the performers’ pockets with a little dough-re-mi.