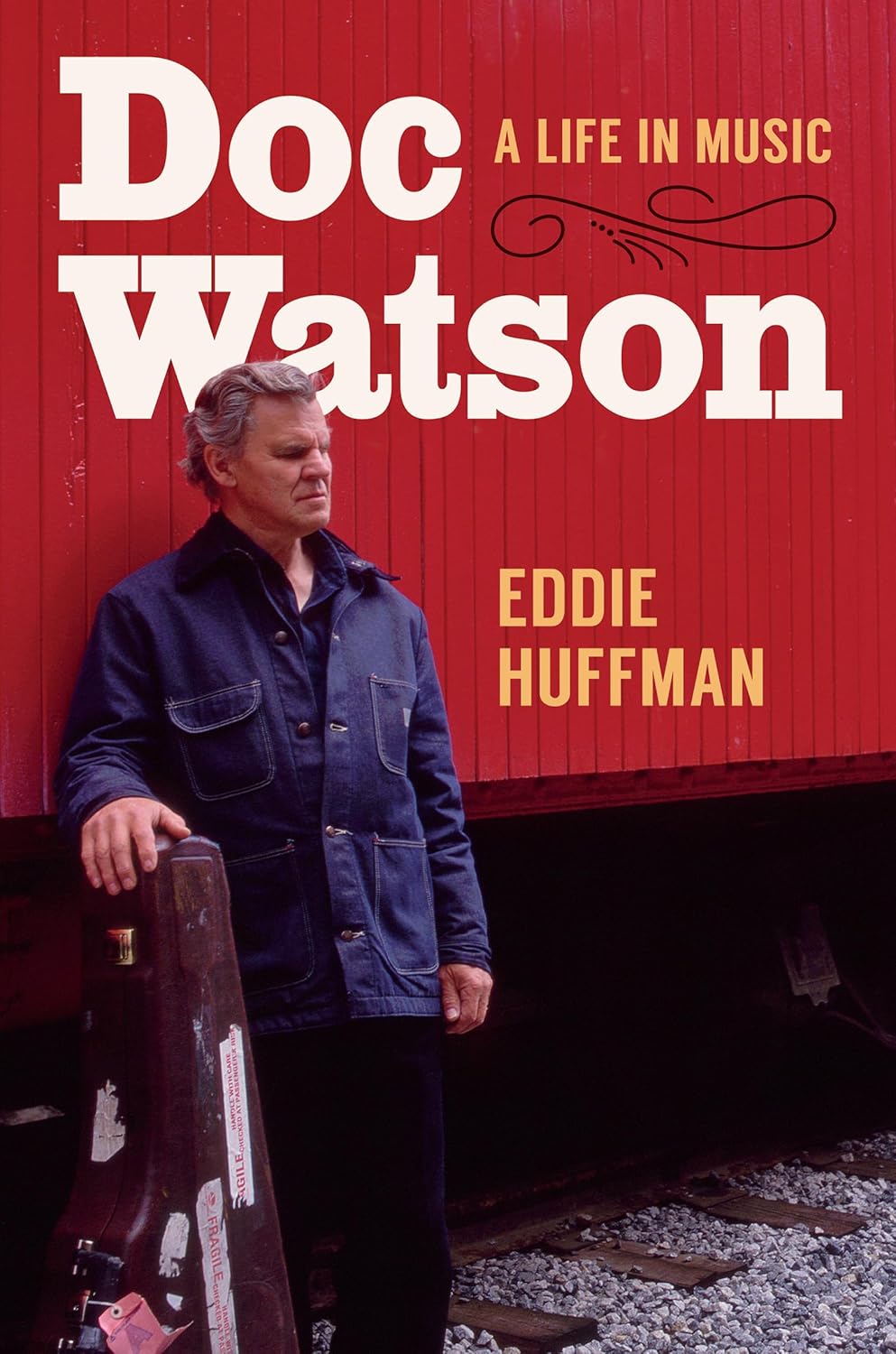

THE READING ROOM: Eddie Huffman Illuminates Doc Watson in ‘Doc Watson: A Life in Music’

As the twenty-first century dawned, Doc Watson looked back over his life and declared—in his typically humble and understated fashion—“If I had planned to do a certain thing and then done it, it’s that I’ve played music that I loved and I did my best to play well.”

As generations of guitarists, songwriters, and fans will attest, the North Carolina native, Watson, often called a musician’s musician, more than played his music well. His style of flatpicking influenced countless pickers—notably Tony Rice and Clarence White—who carried Watson’s legacy to new listeners. As Eddie Huffman points out in his illuminating new biography, Doc Watson: A Life in Music (North Carolina; January 14), “Doc transformed the way acoustic guitar was played for generations of musicians, bringing the six string out of the shadows as a rhythm instrument and onto center stage.”

Drawing on numerous interviews with Watson’s family, friends, and fellow musicians and on archival research, Huffman offers a straight ahead, chronological, account of Watson’s life and music. He had the opportunity to interview Watson himself only once, when Doc counseled Huffman to “slow down” his syntax, because Doc was having a hard time understanding Huffman.

Watson grew up in rural Watauga County, North Carolina, in a family whose motto was “it has flourished beyond expectation,” a fitting message of inspiration for a group of individuals growing up in a remote and mountainous region, who “stayed busy chopping wood, hand washing clothes, and growing and preparing food,” Huffman writes.

Doc—whose given name was Arthel—went blind when he was only one year old, possibly because of tainted silver nitrate drops his grandmother used in his eyes when he was an infant. Despite their constant struggles and his own blindness, Watson and his family entertained themselves with stories and songs. His mother sang old ballads around the house, and Watson first heard the murder ballad “Omie Wise,” which he would include on his first album, from her.

As Huffman observes, “Doc showed a fascination with sound from the beginning: ‘Everything that had a musical tone, if it was a pot, or a cowbell, or whatever, I was always tapping on it to see what it sounded like outside the house.’” He received his first musical instrument when he was five: a Hohner harmonica.

Watson eventually picked up the banjo, but the guitar called to him increasingly: “When a new guitar came into the Watson house, “he took to it like a hawk catching an updraft.” The records his family played on their Victrola introduced him to a wide range of musical styles from country to blues. He learned “My Little Woman, You’re So Sweet,” from a record by Blind Boy Fuller, and he learned from listening to Maybelle Carter to “use a thumb pick and a strum with the fingers,” a style that would be one of the cornerstones of his own playing.

In 1960, Ralph Rinzler, a musicologist who co-founded the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, visited Shouns, Tennessee, to hear banjoist Clarence Ashley and discovered Watson, who was playing electric guitar with Ashley. The two developed a relationship, and Rinzler convinced Watson to start playing acoustic guitar and banjo. Watson and Ashley played for the Friends of Old Time Music in New York City, a concert that introduced Watson and his music to folk music audiences.

Watson’s performance at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival increased his profile, and by 1964 he had recorded his eponymous first album—up until then he had played on the albums of other musicians. In 1964, Watson’s son, Merle—whom he had named for another influential guitarist, Merle Travis—started playing with his father, and the two earned a huge following, and released several albums, until Merle’s death in 1985. Devastated by his son’s death, Watson worked to put together an event to honor Merle’s memory, and on April 30, 1988, the inaugural Merle Watson Memorial Festival—now MerleFest—was launched.

Huffman calls Watson a “superhero” because Doc Watson “had musical abilities that set him apart from mere mortals.” More than a decade after his death, Huffman writes, “Doc’s music shows no signs of fading into obscurity. . .It lives on in Americana music, a genre Doc perfected long before it had a name. . .It lives on in everyone touched by Doc’s smooth baritone, his gentle manner, and his ability to take words, melodies, and stories written by others and return them to the world transformed.”

Doc Watson: A Life in Music provides a portrait of a musician who stretched the boundaries of traditional music in innovative ways. Huffman’s book also serves as a useful introduction to Doc Watson, and it will encourage long-time fans to listen yet once again to Doc’s records.