THE READING ROOM: Five New Music Books You Shouldn’t Leave 2020 Without

The challenge of writing about books — and music or film, for that matter — is sheer volume. Writing about only one book a week means that there are far more books about which I don’t write than those I do. As the year draws to a close, I want to mention a few of the books I didn’t write about this year. Some of the books not on this list, and about which I have not written, will appear in my best-of list next week.

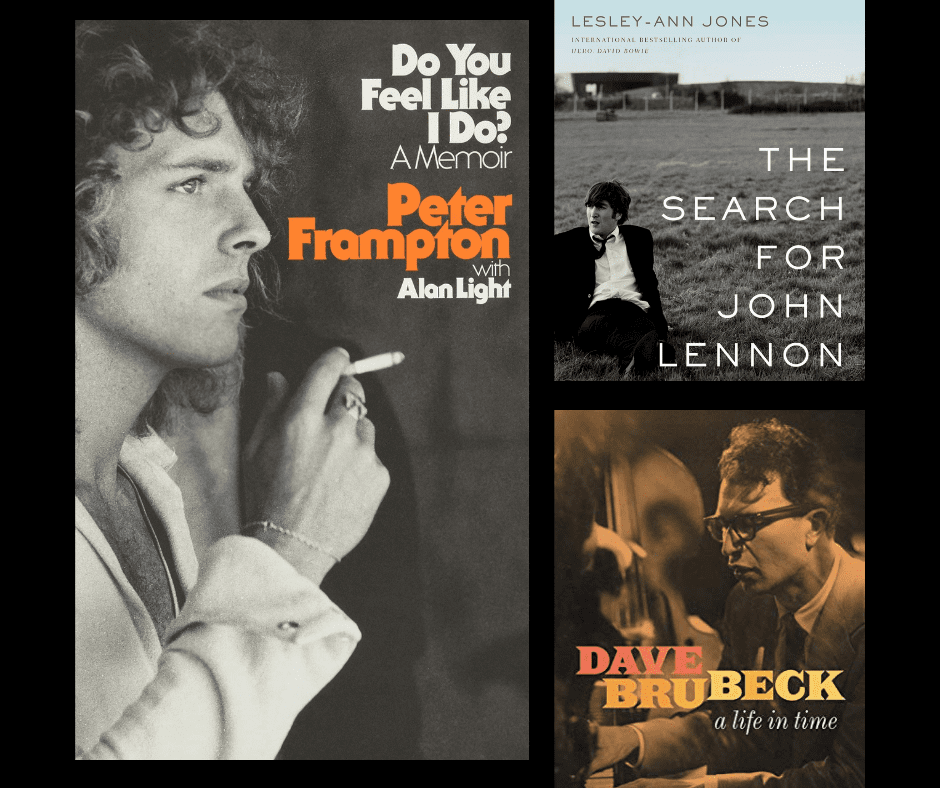

Lesley-Ann Jones, The Search for John Lennon: The Life, Loves, and Death of a Rock Star (Pegasus) — Forty years ago, John Lennon died, gunned down outside his home on New York City’s Upper West Side. Drawing on previously unseen material and new interviews with Lennon’s family and friends, Jones, who’s also written about David Bowie and Freddie Mercury, offers a compelling portrait of the artist, his music, and his legacy. More than other Lennon biographers she focuses on the women in his life: his mother, who gave him up to her sister, Mimi, when he was five; Mimi, who was strict and harsh on him; and Yoko, who made him feel alive and nurtured his creativity. Jones reveals that, contrary to the often-reported stories, Lennon never gave up writing music, recording snippets of it here and there. She reports that in the months before he was killed, Lennon was planning a big comeback tour for 1981. A timely book, and the best of the Lennon biographies.

Craig Brown, 150 Glimpses of the Beatles (FSG) — Just when you think that surely there can’t be one more book on the Beatles, another journalist or historian writes one. Journalist Brown’s lively book lives up to its title, eschewing a linear approach to the life and music of the Fab Four in favor of an impressionist collage of anecdotes, reminiscences, and fan letters. Every “glimpse” reveals some aspect of the band and its life together. In one of his own “glimpses” about the band’s songwriting, Brown writes: “The peculiar power of the Beatles’ music, its magic and its beauty, lies in the intermingling of these opposites [Paul’s and John’s diverse upbringings]. Other groups were raucous or reflective, progressive or traditional, solemn or upbeat, folksy or sexy or aggressive. But when you hear a Beatles album, you feel that all human life is there. As John saw it, when they were composing together, Paul ‘provided a lightness, an optimism, while I would always go for the sadness, the discords, a certain bluesy edge.’ It was this finely balanced push me/pull you tension that made their greatest music so expressive, capable of being both universal and particular at tone and the same time.” Brown’s book is a fan’s notes for fans.

Ken McNab, And in the End: The Last Days of the Beatles (St. Martin’s) — Scottish journalist McNab’s book focuses on a different time in the Beatles’ career, providing a month-by-month glimpse into the final days of the Fab Four. He talks to a number of individuals who witnessed both the lows and highs, the discord and the unity of the group’s last year together. He talks to Les Parrott, for example, one of the cameramen on the Let It Be film project, who describes first-hand the acrimony on the set and the in-fighting that led George Harrison to walk out on the band. In spite of the disharmony of the first half of the year, the band came together in the latter half of the year to make what would be their farewell album, Abbey Road. McNab’s book is often flat and lifeless, but he shines a light on key events in the Beatles’ history that fans of the group will hungrily devour.

Peter Frampton, with Alan Light, Do You Feel Like I Do?: A Memoir (Hachette) — Peter Frampton hit his musical stride early and has spent the rest of his life trying to live up to the promise of his 1976 Frampton Comes Alive! album. His rise to fame was meteoric, playing with Humble Pie from 1968 to 1972, then releasing four solo albums between 1972 and 1975 before hitting the jackpot with that now-famous double live album in 1976. Frampton fell from rock star Olympus just as quickly as he ascended it, though, and he spent much of his life afraid that he’d never be able to reach the heights to which Frampton Comes Alive! had propelled him. He descends into alcohol and drugs and depression and muddles around in them for many years. A near-fatal car crash and his recovery from it, as well as his lifelong passion for music, help him regain his sense of self and his direction. He discovers hope in sobriety and songwriting. Reading Frampton’s rambling memoir is a bit like being condemned to listening eternally to the infernal squawk box of the book’s title song, but Frampton’s fans won’t mind that and will love the book.

Philip Clark, Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time (Da Capo) — Brubeck might be the Rodney Dangerfield of jazz pianists: He never gets any respect, or at least the respect he deserves, among his peers. As jazz historian Lewis Porter recently wrote, “if a pianist says his or her main influence is Brubeck, that will almost guarantee a negative reaction in those circles.” Music journalist Clark’s superb biography provides not only an excellent introduction to Brubeck and his music, but it also offers fans insights into Brubeck’s “absorption in composition, the various ways in which composed music intersected with his unassailable belief in the urgency of improvisation, formed his approach to the piano — which became a laboratory in sound for this composer who improvised and improviser who composed.” Clark draws on the conversations he had with Brubeck over a 10-day period in 2003 during the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s British tour. Brubeck opened up about his unique approach to jazz, the heady days of his “classic” quartet in the 1950s-1960s, and what it was like to hang out with Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, and Miles Davis, among other subjects. Clark’s definitive biography demonstrates why, in the words of President Obama, “you can’t understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck.”