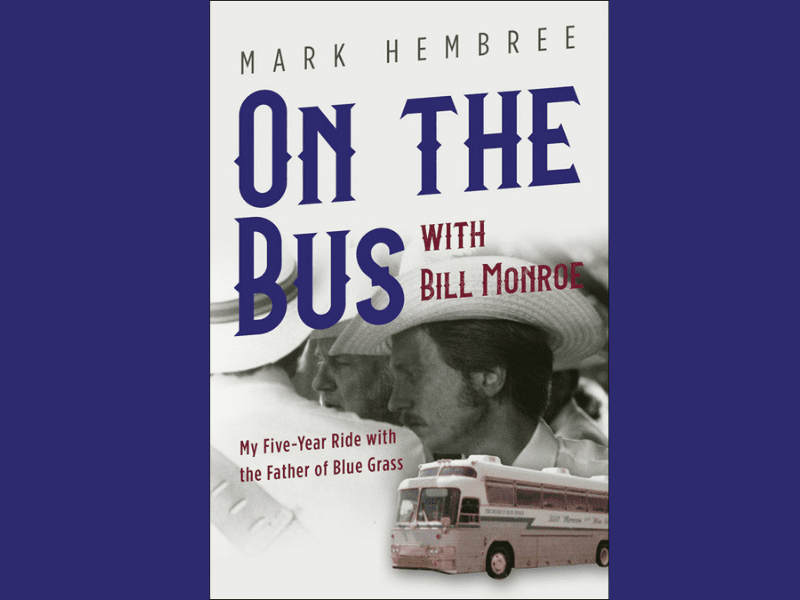

THE READING ROOM: Get ‘On the Bus’ with Blue Grass Boy Mark Hembree

From 1979 to 1984, Mark Hembree played bass with Bill Monroe and The Blue Grass Boys. In his new memoir, On the Bus with Bill Monroe: My Five-Year-Ride with the Father of Blue Grass (Illinois), he tells cracking good stories about the ups and downs of life on the road, playing poker with Bill Monroe, the “gentle side of Bill Monroe,” and eating meals with Bill Monroe. In 73 vignettes, Hembree shares his life and times with Monroe and The Blue Grass Boys in mostly chronological order, from his first audition for Monroe to his final days in the band.

Hembree writes that he started jotting down ideas for the book in 1979, when he was still a member of The Blue Grass Boys, and wrote a “false start forward” in 1985, but put it down and picked it up again in 2018. As he writes, “Back then, I knew my experience was significant and so I did write. I just never felt like I had the perspective to write well enough.” As he points out, though, he doesn’t recall the details of many of the events and incidents in the book (“I grossly underestimated how quickly so much memory could dissipate”), and so he’s labeled each chapter to indicate when the material was written. As he was taking notes and jotting down reflections in 1979, he tried to record things as they were. Hembree observes that he sometimes cringes when he reads some of what he wrote, though, so he labels the material in those chapters as “archival” to let the readers know the information is based on contemporaneous notes. He labels other chapters “recollected” to indicate “episodes [he] remembers well, notes or not.”

A Chicago native, Hembree grew up in Appleton, Wisconsin. In high school, bluegrass wasn’t necessarily his first choice of music to listen to on the radio or to play. Hembree sang in the church choir and played trombone in his high school band, but, as he writes, “nothing stuck until Dad gave me a Gibson J-50 guitar when I was in seventh grade.” From that day, Hembree practiced and played, and played and practiced until, he writes, he could “fake Leo Kotke and John Fahey well enough to get gigs at college coffeehouses before I was old enough to have a driver’s license.”

For the young Hembree, 1972 was a watershed year: He joined an orchestra class, learned to play the bass, and saw a bluegrass band called The Monroe Doctrine at a local college club. “It was an epiphany,” he writes, “here was an acoustic band with more chops than any band I had played in, three-part harmonies, and it was rocking the place.” Hembree “resolves to find or start a bluegrass band.” After high school, he joined a local bluegrass band in Green Bay, and the band had a weekly radio show The Glenmore Country Barndance. A few years later, he goes on the road with a later version of The Monroe Doctrine, but the band was ahead of its time (“long before anything called jamgrass”) and times were lean, so the band eventually fell apart. Hembree, then married, returned with his wife to Wisconsin.

As it turned out, in June 1979, Hembree heard from a friend that Bill Monroe might need a new bass player in his band. After watching Monroe and The Blue Grass Boys play in a town outside Milwaukee, Hembree approached Monroe after the show to ask for an audition. At the time, Hembree was sporting a ponytail, which was apparently unacceptable, so he told Monroe that he could “get it cut in a second.” The next morning, he came back for an audition; about two weeks later, Monroe called to ask how soon Hembree could be in Nashville. Two weeks after the call, Hembree showed up at Monroe’s office, waited around for Monroe, then boarded the bus with the band to head to Virginia to play his first show with them.

As he tells it, though, that first day was pretty lonely, since everybody had left him and gone off for breakfast. “When I awoke around dawn the next morning…we were parked on a county fairgrounds…It was another very long day for me. The hours dragged on, made longer and stranger by the fact that nobody talked to me…Shining shoes is one of the few activities I shared with the band.” Even more worrisome for Hembree, at least at that moment, was that he had never played with the band, except for his audition, and he wondered if the band would rehearse before the show. “Finally, around 7:30 p.m., the Boys began dressing for the show. I got dressed, carried my bass to a backstage room, and tuned up. We warmed up with two or three tunes, and then it was time to go on. Just like that, I was a Blue Grass Boy.”

On the Bus really shines in its details. In one archival chapter, Hembree vividly recalls a certain look that Monroe would give. He writes, “as intense as the music he plays is the fearsome gaze Monroe can fix on someone who displeases him. Not just any baleful glare or icy stare—it’s more like a searing, psychic laser. Former band members still shudder and laugh when you mention getting The Eye.” In another, he recalls the dilapidated bus that Monroe and the band rode from show to show. While Hembree initially considered the Silver Eagle bus an upgrade from the Chevy van he traveled in with the Monroe Doctrine, but soon the novelty wears off. As he writes, and the bus stank from “socks, drawers, pickled vegetables and rotted, potted meats, body odor, mouth odor, and diesel fumes…apart from these considerations, the bus is mechanically deficient.”

Throughout his time on tour, Hembree discovered that the best chance to talk to Bill Monroe was at the breakfast, lunch, or supper table. The bandleader loved his food, after all. Those conversations became a way for Hembree to gauge Monroe’s mood and where the bass player stood with Monroe: “there was a fine line between him poking fun at you and running you down.” And, of course, Monroe is famous for some of his observations about food. “I love ham. You can’t hurt ham,” he said. On cold, stale biscuits: “Man, I could really curve one of these!” On over easy eggs: “That hen’s worked hard to keep them two parts separate, and now you go running them all together.”

Over all, On the Bus is a rollicking ride down the bluegrass road with the Father of Bluegrass and his band, and Hembree serves as a truly entertaining tour guide.