THE READING ROOM: ‘Joni on Joni’ Traces Mitchell’s Career through Interviews and More

On Nov. 7, 2018, Joni Mitchell turned 75, and artists including Emmylou Harris, Brandi Carlile, Norah Jones, Chaka Khan, Seal, Graham Nash, James Taylor, and Kris Kristofferson feted her at a pair of sold-out shows at The Music Center’s Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Each artist delivered his or her own take on a favorite Mitchell song: Taylor performed “River” and “Woodstock,” Glen Hansard offered his version of “Coyote” and “The Boho Dream,” Harris sang “The Magdalene Laundries,” while Graham Nash sang “Our House,” which he famously wrote about his and Mitchell’s time together. A DVD of the celebration will be released in a few weeks (March 29), but the CD is available now.

The release of the DVD and the CD reminds us once again how brilliantly Mitchell paints with her songs. She moves from the broad brushstrokes of social commentary—though she seldom thought of her songs as protest songs—in songs such “Woodstock” or “Big Yellow Taxi” to the pointillism of relationships in songs such as “Coyote” to the surrealistic swaths of color on her Mingus album. Mitchell’s radiance outshines so many other songwriters because she never sits still creatively. Mitchell moved—not always gracefully for her fans—from the early folkish tunes to the free-flowing chanting of Hejira to the collaborations with Tom Scott and the L.A. Express to her work with Charles Mingus. She’s always looking to the next sound, to the next moment, to the next idea, to the next image.

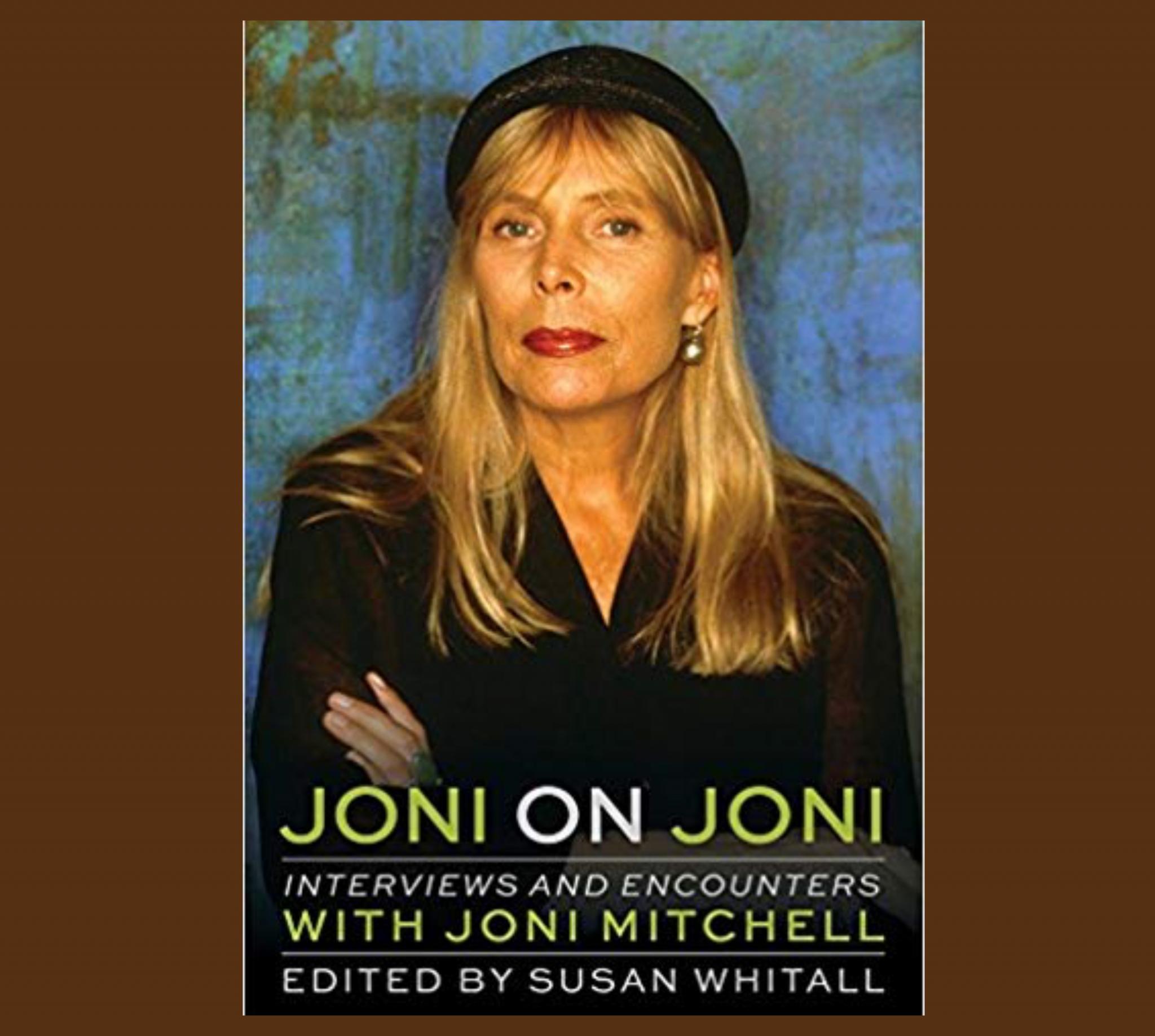

Nicely timed to release on the day before Mitchell’s birthday, music journalist Susan Whitall’s Joni on Joni: Interviews and Encounters with Joni Mitchell (Chicago Review Press) offers glimpses into Mitchell’s development as a songwriter and artist, as well as her takes on a wide variety of matters from Dylan and Taylor Swift to musical pigeonholes, her cats, and death. The interviews—gathered from American, British, Canadian, and European magazines and newspapers—are arranged chronologically from 1966 to 2014, and Whitall (Women of Motown) provides short introductions to each interview that help set the context for that particular conversation. Scattered through the book are anecdotes pulled from other interviews—placed in little boxes titled “Joni Said”—that reveal Mitchell’s thoughts on various topics.

In one of the earliest interviews (1968) in the book, Dave Wilson of Broadside asks Mitchell what she believes is the trademark of her growth. Mitchell’s response reveals her always probing mind and enduring thoughtfulness: “I think I’m a better poet now, and my melodies are much more complex. The music is, and this is a dirty word to use, much more intellectual. It’s more complicated; it has more meat to it. So things like ‘Carnival in Kenora,’ which is just a pretty little courtship song that people loved—I’m not writing any more like that. I get halfway through them and I realize they’re not saying anything and I throw them aside. I have more philosophy in my songs; it’s not really protest, it’s more contemporary.”

During a 1970 interview with Ray Connolly in London’s Evening Standard, Mitchell comments on American’s propensity to ruin the beauty of nature: “When I was in Hawaii, I arrived at the hotel at night and went straight to bed. When I woke up the next day, I looked out of the window and it was so beautiful, everything was so green and there were white birds flying around, and then I looked down and there was a great big parking lot. That’s what Americans do. They take the most beautiful parts of the continent and build hotels and put up posters and all of that and ruin it completely.”

In a couple of interviews in Canada from 2005, Mitchell reflects on the state of contemporary music and on selling your soul. On the first topic she says: “It’s contrived money music. You know, you hear young artists talking and they’re talking demographics. And I saw one girl, a fourteen-year-old, you know, with a brand new bosom and she shoved it at the camera and said, ‘I want to get my music to the world!’ you know? And I thought, There’s no muse in this. There’s a drive to be looked at, you know? So this is not—these are not creative people; these are created people.” On the second topic, Mitchell offers her candid and blunt wisdom: “I say to young people, well, do you want to be a star, or do you want to be an artist? And they go dink dink, they don’t know, and I say, you better know right now, because if you make any compromise, if you want to be an artist and they tell you do this, do that—you’re screwed, you sold your soul to the devil.”

The centerpiece of the book is Cameron Crowe’s never-before-published 1979 Rolling Stone interview with Mitchell. It’s a wide-ranging conversation that arrived after Mitchell had shunned the magazine for the previous eight years since they had published a sort of family tree illustration of the many lovers to whom Mitchell had been connected. She admired Crowe and the two became close friends after the interview. Almost every page of the interview shimmers with insight, and you can feel the ease and comfort with which the two converse. Early in the interview, Mitchell provides a memorable image of the evolution of artist, especially as seen from the perspective of the music business: “It’s typical in this society that is so conscious of being number one and winning; the most you can really get out of it is a four-year run, just the same as in the political arena. The first year, there’s the courtship prior to the election—prior to, say, the first platinum album. Then suddenly you become the king or queen of rock & roll. You have, possibly, one favorable year of office, and then they start to tear you down. So if your goals end at a platinum album or being king or queen of your idiom, when you inevitably come down from that office, you’re going to be heartbroken. Nobody likes to have less than what he had before. My goals have been to constantly remain interested in music. I see myself as a musical student. That’s why this project with Charles [Mingus] was such a great opportunity. Here was a chance to learn, from a legitimately great artist, about a brand new idiom that I had only been flirting with before.”

Joni on Joni gives us more opportunities to glimpse the many gem-like facets of Mitchell’s mind and art. It celebrates her wisdom, and it serves as a nice companion to a listening tour through her musical oeuvre.