THE READING ROOM: ‘Mandolin Man’ Shares Story and Influence of Roland White

Roland White, who died earlier this year, was never a showman; he was a steady presence on whatever stage he stood, or away from the stage entirely, always ready to contribute where he could. But White’s generosity as musician and as a person touched bluegrass music in ways that will live forever in conversations and in the music itself. He’s sorely missed, but we’re just the drop of a needle away from some of those exhilarating solos with his brother Clarence White on “Listen to the Mockingbird” or “Nine Pound Hammer” on the Kentucky Colonels’ now-iconic album Appalachian Swing!

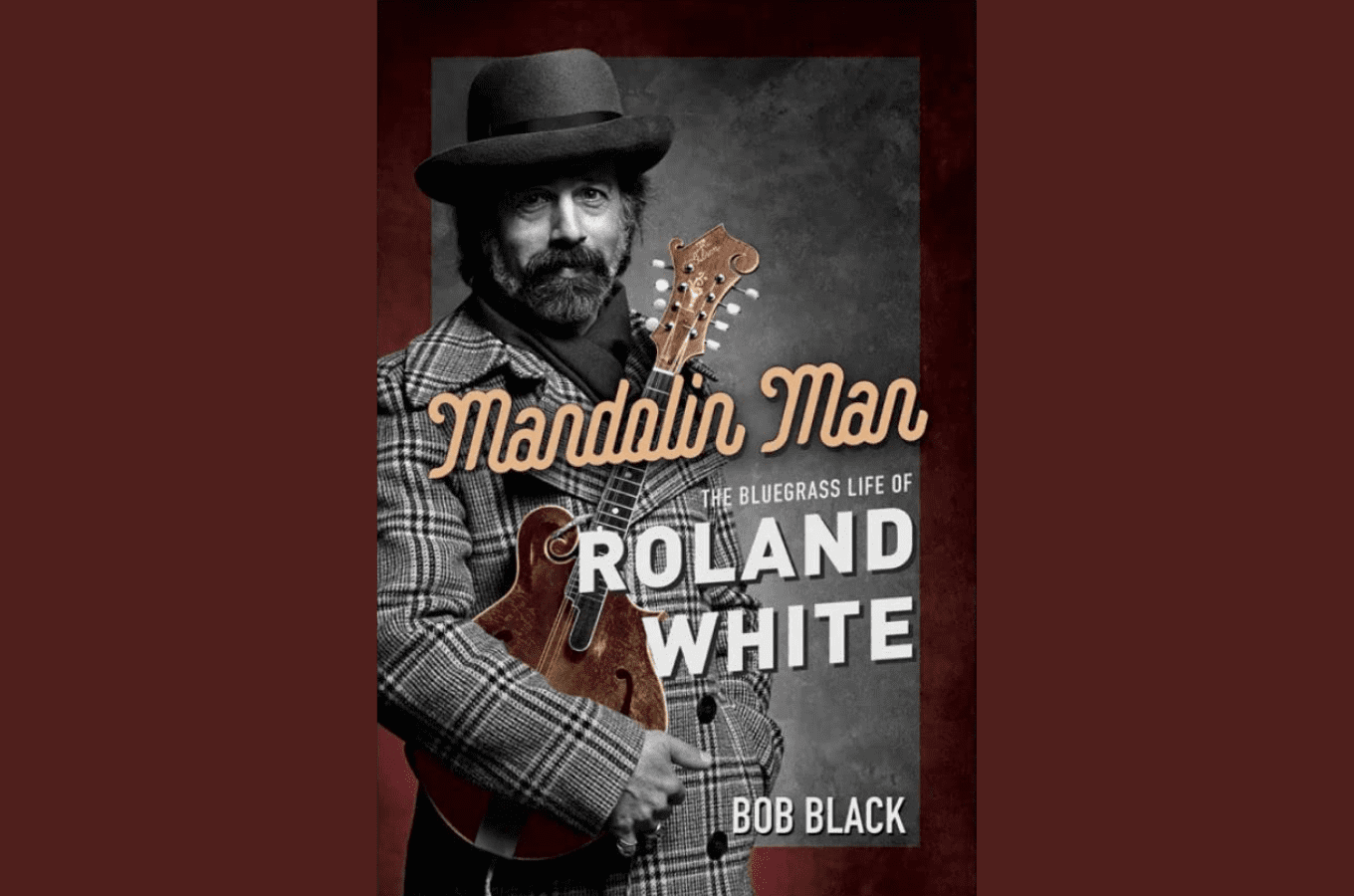

Now, thanks to White’s friend, banjo player Bob Black, who played with Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys and who co-founded Banjoy, we have an affectionate fan’s notes and tribute to White in the new book Mandolin Man: The Bluegrass Life of Roland White (Illinois).

Roland White was born to play bluegrass. He was part of a music-loving family; his mother, Mildred, would “kick off her shoes and dance whenever she heard her favorite songs,” and his father, Eric Sr., played fiddle, guitar, tenor banjo, and harmonica, and would often get up before breakfast to play a few tunes. When he was 6, Roland made attempts to play some chords on the guitar so he could accompany his father’s fiddling; he also tried to play the fiddle with his father’s encouragement. White’s father was always collecting instruments, and one day White came home from school to find his father home early from work playing a mandolin, which he gave to White. When he was 8, White told his mother that he wanted to sing on the radio someday; she encouraged him and told him that if he kept practicing he’d be on the radio one day. White was fortunate to have siblings also deeply interested in music, and by the time he was 11, his younger sister and brothers, including Clarence, who was 5, were making music with him.

In 1954, when Roland was 16, the family moved from Maine to Burbank, California. Not long after their arrival, the three boys — Eric, Clarence, and Roland — and their sister, JoAnne, made their debut at the Riverside Rancho, where they competed in a talent show as the Country Kids, and won. Eventually, the family group evolved from the Three Little Country Boys to the Country Boys. The Country Boys added dobro player LeRoy McNees and banjo player Billy Ray Latham and made their way to Nashville, where they met Grandpa Jones and The Foggy Mountain Boys. They returned to California with new energy to make bluegrass music. By 1961, The Country Boys had put out a record, and Andy Griffith heard it; he invited them to be on an episode of his show in 1961, where the group backed up Griffith.

When White was drafted in 1961, The Country Boys played on, but they never replaced him. Before White returned from his stint in the service the group had transformed — with the help of Johnny Bond, Tex Ritter, Merle Travis, and Joe Maphis — into the Kentucky Colonels, and they had recorded an album, The New Sound of Bluegrass America. When White returned in the fall of 1963, he rejoined the group and they started playing in various venues around California, including college campuses, where the audiences loved the music. In early 1964, the group made their now-famous album Appalachian Swing!. As Black points out, “the album, though short, was a masterpiece with unmatched interplay between the instruments. Clarence’s guitar was a full-fledged lead instrument as well as a rhythm instrument — something that had never been before in a bluegrass setting. The album started off with a Ralph Stanley banjo tune ‘Clinch Mountain Backstep.’ Roland played his mandolin solos using some of the archaic mountain scales of early old-time music, giving the tune a timeless feeling. The second tune, ‘Nine Pound Hammer,’ was a mandolin-guitar duet. Clarence’s solos started out bluesy and then became more straightforward with each successive turn he took, whereas Roland’s mandolin solos started out in a very traditional manner and became bluesier on later solos. Clarence took ‘John Henry’ in a new direction with several blues guitar licks that put a personal stamp on the old folk tune, making it a fresh and exciting experience for both player and listener.”

Moving chronologically, Black offers details on White’s musical career following the Kentucky Colonels from Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys (1967–69), Lester Flatt and the Nashville Grass (1969–73), and the New Kentucky Colonels (1973), though his years with Country Gazette (1973–87), the Nashville Brass Band (1989–2000), and the Roland White Band (2000–21).

As Black reflects on White’s career: “Roland’s time spent working for Bill Monroe at low pay and long hours playing guitar (not even his primary instrument) was like serving an apprenticeship. The Nashville Grass was a continuation of that. Those two jobs provided a springboard for Roland to achieve his full personal potential as a musician with his own creative independence. Country Gazette and The Nashville Bluegrass band were platforms for him to display those gifts, no longer restrained by orthodox interpretations. The Roland White Band is the culmination of his lifetime of personal musical experience, and his bandmates have the good fortune to be beneficiaries of his hard-won expertise.”

In a valuable appendix, Black provides thumbnail sketches of people, bands, and venues mentioned in the book. Another appendix offers a listing of White’s instructional materials that are available on his website.

Black concludes his genial tribute to White with a sketch of White as a musician willing to take chances, musically and professionally. “Roland sees his playing as like climbing a tree. ‘The melody is like the tree trunk,’ he told me. ‘I’ll start down here at the bottom, then go out on a limb a little bit, fall off, and then I’ll climb back up and test another limb.’” In addition, observes Black, “striking out into uncharted territory has been the hallmark of [White’s] career, beginning with the Three Little Country Boys and culminating in the Roland White Band.”

Mandolin Man is as close to a biography as we have at the moment, and Black draws on interviews with friends and fellow musicians to offer a warm portrait of White and his contributions to bluegrass. Fans of Roland White will certainly appreciate Black’s book, and turn its pages as they listen to White’s enduring music.