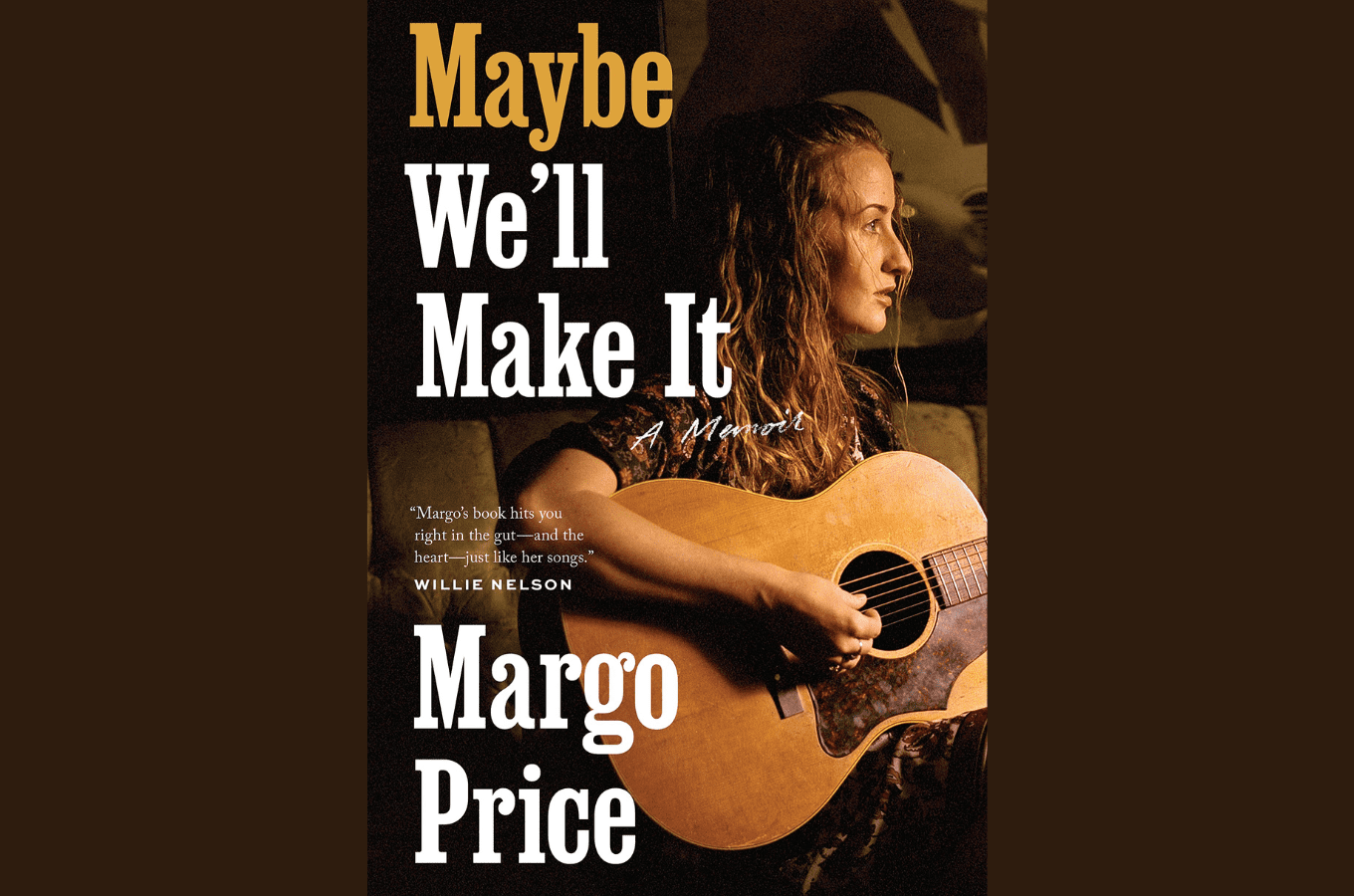

THE READING ROOM: Margo Price Details Pain and Progress in Memoir ‘Maybe We’ll Make It’

Two-thirds of the way through her searing new autobiography, Maybe We’ll Make It (Texas), Margo Price shares the ways that music has transformed her pain — and Price has lived through more than her share of pain, especially losing one of her twin boys to an unsuccessful (actually, a botched) attempt to correct a heart condition.

Price fell hard back into drinking after her son Ezra’s death in 2010 and had an affair with the guitarist in her and her husband’s band. Redemption came in the form of classic country music: “As Buffalo Clover was deteriorating, I fell under the influence of classic country music. I had always appreciated it, but now I obsessed over it.”

Price dove deeply into the music of Waylon and Willie, Jessi Colter, George Jones, Hank Williams, and Tammy Wynette. Most of all, she admits, “I liked the kind of artists who didn’t shy away from real pain. I related to songs about love and death, drinking and cheating, truth and betrayal, because they were what I was living. Songs that punch you in the gut, like Townes Van Zandt’s ‘Waitin’ Around to Die.’ Townes was dangerous and vulnerable, damaged yet perfect, both crooked and straight, and full of pain though he covered it up with self-deprecating humor. Townes died depressed, drunk, and close to destitute, never knowing how much of an impact his music would have on future generations. I related to all of that.”

Soon after, Price pulled together her own side project — as she calls it — called Margo and the Price Tags, a band that played around Nashville that included Kevin Black or Jeremy Ivey, Price’s husband, on bass; Sturgill Simpson, Kenny Vaughan, or Mark Sloan on guitar; Kristin Weber on fiddle; Pete Finney or Alex Munoz on pedal steel and dobro; Eric Whitman on keys; and Moises Pallido or Taylor Powell on drums. Playing classic country and roots cover songs with the Price Tags invigorated Price and kickstarted her writing again, and she started closing out the evening’s sets with “Since You Put Me Down” and “Hurtin’ (On the Bottle),” two songs that would make it onto her debut studio album, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, in 2016.

But pain was not finished with Price just yet. Despite the accolades she received for her live show, she faced an uphill battle getting signed and making her album. One label representative told her that he was “sad to say that we have to pass on Margo. We like the album, but we already have two girls on our label and we just can’t sign any more.” Price reflects on this moment with the same gritty defiance that animates her approach to music and to her story: “The specific rejection stuck with me for a long time because it wasn’t personal, it was sexist. I wondered how many other talented women out there weren’t being signed because they were women. I carry that moment with me today, knowing that I’ve always had to work twice as hard as men to get what I want. But the way I figure, twice the work means twice the practice, and maybe that just makes me stronger in the end.”

As with any autobiography, Price’s chronicles the singer’s childhood and youth. When she was 7, Price’s parents bought her and her sisters a piano. Price had been writing songs and poems from the time she was in first grade and singing them a cappella into a tape recorder. “With piano,” she writes, “I could finally accompany myself.” She got a guitar in eighth grade and sat for hours in her room practicing. In high school, Price dropped psilocybin for the first time, and as she reflects on her trip she realizes: “Music had never felt more symbolic. We listened to the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and I watched the patterns of the curtains mutating before my eyes. It’s really hard to describe what that first intense trip was like, but it felt like a conversation with God. It stripped away parts of my ego and revealed to me what I already knew in my heart. We are not our bodies, we are souls, temporarily imprisoned inside of this human experience. My value was not in my beauty or the lack thereof. The mushroom trip shined a light on my insecurities and made me face my fears about the future. …There was renewed hope in my dreams. In that moment, I had found the secret to understanding the universe and what my role was in it: I would drop out of school and become a musician.”

Price has a knack for telling stories and drawing readers into her life and experience, and Maybe We’ll Make It radiates with her bright candor; she’s not interested in hiding her heart in the shadows and covering her feelings with darkness. Price bares her soul and the jaggedness of her emotions, making Maybe We’ll Make It one of the best music memoirs so far this year.