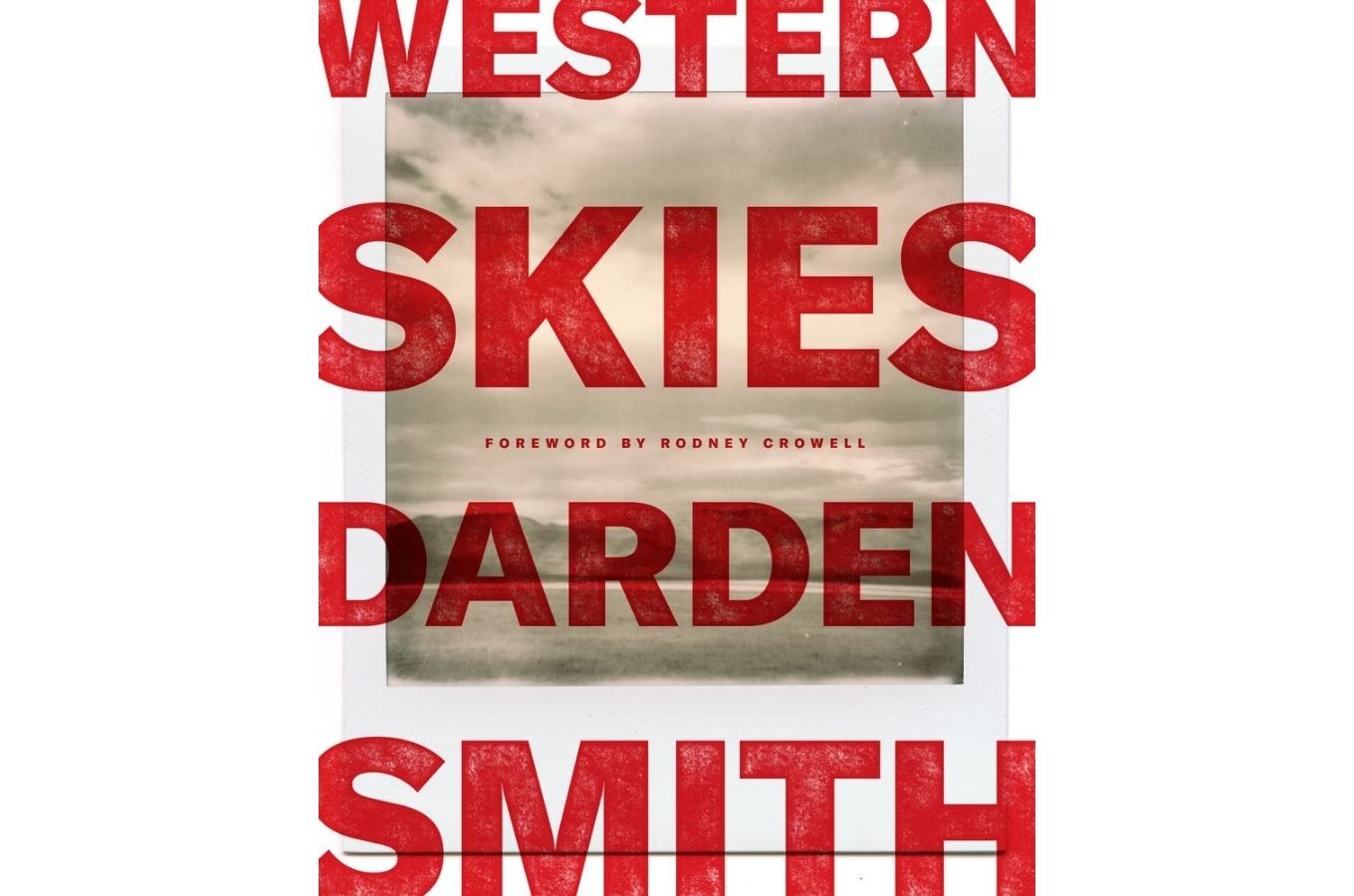

THE READING ROOM: On ‘Western Skies” Project, Darden Smith Lives a Landscape in Photos, Words, and Songs

Darden Smith’s stunning new project, Western Skies, exquisitely captures the expansiveness of the landscape of Texas and the American Southwest in photographs, essays, poems, and songs. In a book and album of the same title, Smith produces a cinematic take on a ragged, isolated terrain swept by windstorms and dotted with the detritus discarded by nature’s disuse and human migration. Smith’s grainy black-and-white Polaroid shots convey the desolate beauty of untouched spaces, as well as the jagged grandeur of found objects such as gas pumps and old tires.

Smith co-founded Songwriting with Soldiers, which pairs veterans with musicians to tap the transformational possibilities of collaborative songwriting, with Mary Judd in 2012. During the pandemic, Smith embarked on a series of solo drives between Austin, where he is based, and southern Arizona for writing projects with veterans. After happening on an old Polaroid camera in his garage, he started documenting these trips with photographs. At the same time, he began dictating poems and snatches of songs as he was driving.

In the introduction to his book, Smith gives a glimpse into the way the project developed: “Western Skies started with the photographs, all of them taken with an old Polaroid camera resurrected from a box in my garage sometime in the summer of 2020. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, but I sure like to take pictures. The idea of using such an outdated way of capturing images struck me as the perfect antidote to the hectic digital nature of these times. My usual way of working was to see something, stop the car, take the photo then immediately get back in and drive off, letting it develop in a box on the front seat as the miles clicked over. I had one shot, maybe two, for each idea and there were many, many mistakes. Part of the joy was the randomness of it, and having almost zero control over how the image came out. It’s kind of a ridiculous and expensive way to work. Each shot cost about as much as a good espresso, so that became my calculator: was this picture worth a coffee? If not, I’d just walk away. After a time, I found myself not taking almost as many photos as I did.”

His poems and song lyrics convey the vastness of time and space, as well as humanity’s yearning for stasis even in the midst of the ever-changing tides of the natural world. In “The Ocean under the Desert,” for example, the first stanza opens by looking back: “All of this used to be underwater / From the freeway tangles of Houston and Dallas / Across Austin to El Paso.” As the poem continues, it acknowledges that nature “knows there is nothing permanent” and that the desert “will again be submerged.” In contrast, humans think the way they see the desert now is the way it has always been: “We yearn in our mind, in our walls, bridges / Houses and laws, songs and sex / For some lasting place / Something that stays forever.” In the final stanza, the speaker hears the voice of a crow “whisper truth”: “That I am nothing compared to rock / That I and everything I do and think / Will one day be dust.” Far from being pessimistic, the poem embraces a Whitman-esque spirit of the unity of humanity and nature and of the ever-renewing storms that refresh and replenish body, world, and spirit.

In “Rain,” Smith, like William Carlos Williams, creates a vivid image of the gentleness of a slow rain and the savage dread of torrential downpours. Getting caught in such a downpour, the speaker feels the drops between his “shoulder blades” and thinks of “the hidden seed / Buried long ago / In some other storm / Knowing I’ll never see its bloom” and that “rarely / Do we witness / The becoming of our days.” “The Signs of Others” acknowledges the marks of those travelers who have gone before the speaker, and the speaker, too, “writes [his] name across a cloudless sky” so that years from now others will know he has traveled the same paths and blazed a trail.

Smith’s album evokes the spaciousness not only of the Western landscape but of the human psyche. Spare and airy musical settings loop around evocative lyrics that sing of love kept and lost, human desolation, and hope. “Miles Between,” the opening track, tumbles in over gently tinkling piano notes and chords that swiftly cascade into a rushing torrent that evokes the tumultuousness of distance between human hearts yearning for each other. The title cuts many ways since the “miles between” refers not only to physical separation and emotional separation, but also to the distance that too often yawns between talking and listening. “Running Out of Time,” a gorgeous love ballad reminiscent of Van Morrison’s “Brand New Day,” delivers a heart-rending promise that the singer’s never going to lose a moment loving his lover.

The title track shimmers with steel guitar and gentle finger-picked guitar as the clouds of love and memory swirl around each other. The bluesy “Not Tomorrow Yet,” co-written with James House (who also provides harmony vocals on most of the album) smolders with tension between the chasms of doubt and anxiety, while the Neil Young-like “Turn the Other Cheek” pleads for everyone to “show a little mercy and forgiveness / In what you do and what you say.” The album closes with the sparse and sparkling “Hummingbird,” which hovers over the sweetness of love and the closeness of desire.

On both his album and in his book, Smith is a guide through the jagged emptiness of the human heart, the devastating bleakness of the desert, and the shining hope of love. His songs, poems, and photographs sweep us off our feet, transporting us to the landscapes of his heart, his memory, and his travels.