THE READING ROOM: Patti Smith’s Thoughtful Year

Somewhere between waking and dreaming Patti Smith wanders, extolling the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, puncturing the ballooning apathy of American culture following the 2016 presidential election, and looking back on, and gazing forward into, times marked by loss and measured by the pace of her reveries. Like Susan Sontag before her, Smith immerses us in worlds that are at once foreign and familiar. Like Sontag, Smith gambols in the fields of popular culture, skipping from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain to Nina Simone to Chunky bars to Gauloises to J.G. Ballard to Japanese anime to Gidget to Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues in her usual peripatetic prose. There is stark splendor in Smith’s writing, for she allows us to see the hope and beauty of a dreamed-of world — well, the world as it might be without the bloatedness of human conceit. And when we read one of her memoirs, we submerse ourselves in her wanderings and find ourselves somewhere between waking and dreaming.

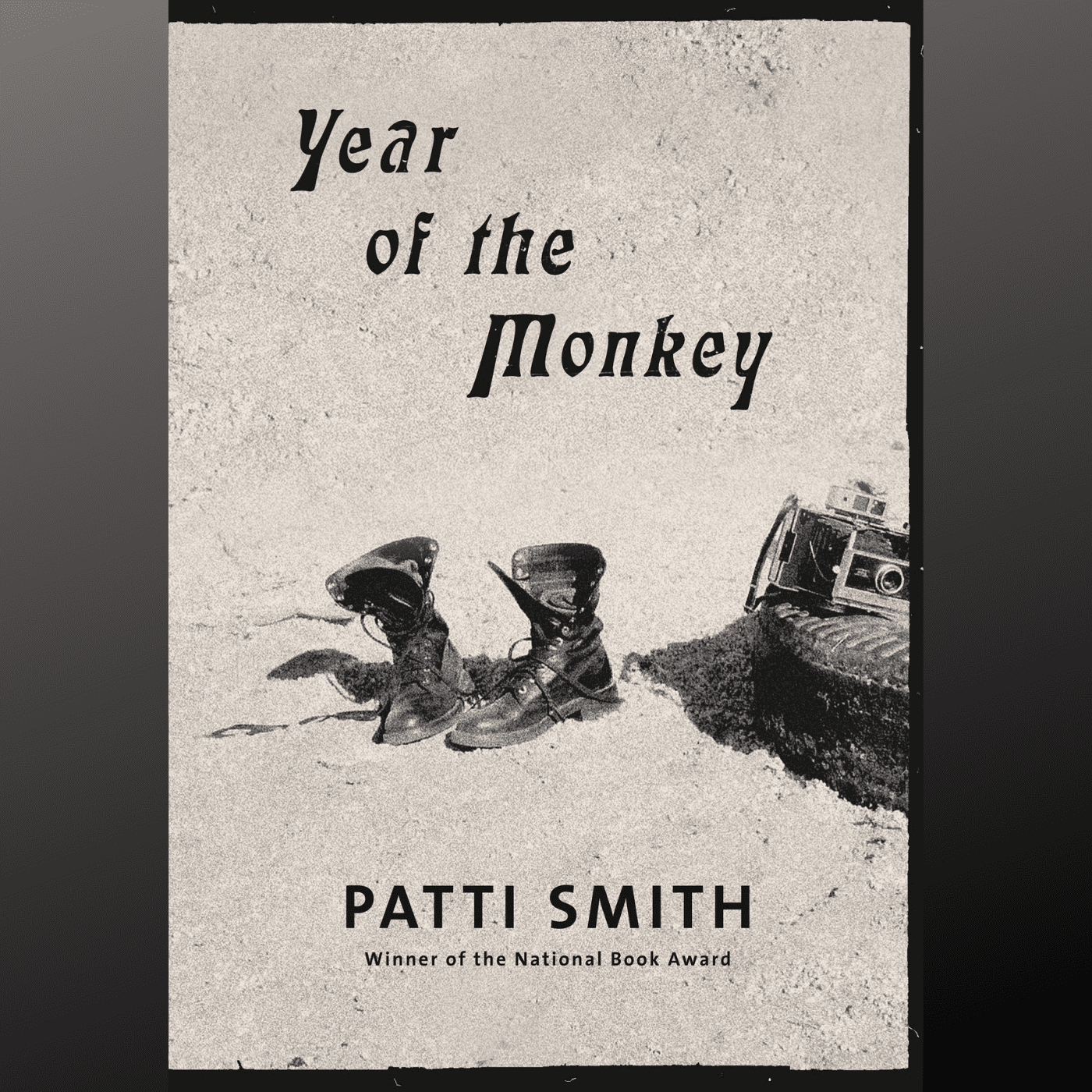

In her newest memoir, Year of the Monkey (Knopf), out Sept. 24, Smith reflects on the raggedness of life and love and the sheer fabric or reality that separates life and death, illusion and reality. While the canvas of her prose painting is 2016, the year of her 70th birthday, which coincides with the year of the monkey in the Chinese zodiac, the colorful strokes with which she paints provide the beauty of the book. The year opens “way out west” when she pulls up in front of the Dream Motel in Santa Cruz at 3 a.m. on New Year’s Day after an hourlong ride from San Francisco and the last of three nights performing at the Fillmore. She takes a walk in search of coffee and, perhaps, breakfast. She finds, of course, that the cafes are shuttered for the day, and she sits outside on a bench “going over the edges of the night before.” She digs in her pockets for a pencil to jot down the “chain of phrases” that fly into her mind: “Ashen birds circling the city dusted with night / Vagrant meadows adorned with mist / A mythic palace that was yet a forest / Leaves that are but leaves.”

Year of the Monkey is a grand tour of Smith’s divagations, and, like Rilke’s Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, or Genet’s The Thief’s Journal, Smith’s meditations on her excursions into her identity and the world around her fill every page of her book with poignant poetic pictures that meld life and imagination. During the year in which her memoir is set, Smith travels, sometimes coming home to her apartment in New York City for a few days, other times heading to Kentucky to spend a few days with her close friend, the playwright Sam Shepherd, whom she is helping as he writes a script. Shepherd’s death is the subject of Smith’s “kind of an epilogue,” where sentences rush after one another in staccato prose and without a break to separate into paragraphs. In the middle of winter, a cold rain closes in on her apartment in New York, and water pours through her leaking skylight before she can gather up books and clothes from the floor. She reflects on this moment: “I know something of this so-called game. Havoc: an uppercase game with a lowercase deity, spelling nothing but trouble for the unwary participant. One finds himself assailed with components of a dreadful equation. One evil eye, two spinning stars, perpetual tears and gears. Unequivocal havoc instigated by the current lunar god and his band of winged monkeys, a pervasive lot who once preyed upon the unsuspecting Dorothy in the hypnotic fields of Oz.”

On the “terrible soap opera called the American election,” she declares that “the bully bellowed. Silence ruled … All hail our American apathy, all hail the twisted wisdom of the Electoral College.”

One night in New York City, unable to sleep, Smith is scrolling through some channels on the television and lands on an infomercial featuring the Go-Go’s “We Got the Beat.” Smith muses about Belinda Carlisle: “Her exuberance was infectious. I imagined a nonviolent hubris spreading across the land, like the boys in West Side Story buoyed by a mounting swagger, singing When You’re a Jet … Hundreds of thousands of girls and boys flooding the open perimeters, taking on Belinda Carlisle’s moves, singing We got the beat. And soldiers laying down their arms and sailors leaving their posts and thieves the scenes of their crimes and all at once we’re in the epicenter of one grand musical. No power, no race, no religion, no apologies. And with this vast spectacle racing through my mind, some part of me leapt up and sashayed down the road, entering the scene, joining the chorus increasing ad infinitum, like William Blake’s angels streaming from the turning pages of the book of life.”

Year of the Monkey likewise releases angels as we turn its pages and as we, with Smith, imagine a world yet hoped for, recognizing that the trouble with dreaming is the waking up. Year of the Monkey joins Just Kids, M Train, and Devotion (Why I Write) as stages along Smith’s life’s way, each one offering glimpses of Smith’s wandering and wondering and of shards of her poetic prose.