THE READING ROOM: Remembering Charlie Daniels Through His Memoir

When Charlie Daniels died last week, the tributes and accolades poured in from friends and fellow musicians. In their own ways, they each focused on Daniels’ contribution to music, his deep religious faith, and his loyal friendship and generosity and grace.

Doug Gray of the Marshall Tucker Band — which, along with the Charlie Daniels Band, and others, ushered in a new wave of Southern rock — reflected that “It is a sad day for a southern gentleman. A soft spoken Godly man. A man I have known for 50 years. Yes my heart is broken but Hazel and Charlie Jr. have all of us holding them with the strength that Mr. Daniels has given us through the years. We are missing a man that already has the hands of his great God holding him. I have no words.”

Country singer Aaron Tippin talked about Daniels’ influence on him: “It’s so hard to put into words what an influence Charlie’s music was on me and on everyone who ever heard it. … There was nothing he couldn’t do. He will be so missed in this world. Sending prayers to Hazel and all of his family.”

Country Music Hall of Famer Ronnie Milsap summed up best all the ways that Daniels contributed to the world: “Charlie Daniels embodied the fire of the South. He blurred lines between rock and country, when rock didn’t think country was cool, and his Volunteer Jams weren’t just legendary, they brought people from both of those worlds together. He was a patriot, a proud American, a world class musician, an incredible showman, as well as a wonderful father, husband, grandpa and friend. We’re all so sad to lose him, but if I know Charlie, he’s up in heaven, rosining up his bow and getting ready to let those fingers fly! Godspeed, my friend, you’re home.”

Charlie Daniels will be remembered for his music, especially “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” “The South’s Gonna Do It Again,” “Long Haired Country Boy,” and “Uneasy Rider,” but Daniels was also a producer and songwriter. Many people first heard Daniels’ novelty song “Uneasy Rider,” from his third album Honey in the Rock, and they associated him with hippies and the rebellion against rednecks. As Daniels began to fly his Southern rock flag, he played fiddle with the Marshall Tucker Band on songs such as “Searchin’ For a Rainbow” and “Carolina Dreams,” and often played with the Southern rockers Barefoot Jerry, whose leader, Wayne Moss, played on Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. Daniels moved on from Southern rock to country, bluegrass, and gospel, but he continued all his life to support a confluence of musical styles — his last album was a blues album with his band called the Beau Weevils titled Songs in the Key of E. He was also a producer (he produced The Youngbloods’ Elephant Mountain), a sideman on Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, and co-writer of “It Hurts Me” with his friend Bob Johnston, which became a hit for Elvis.

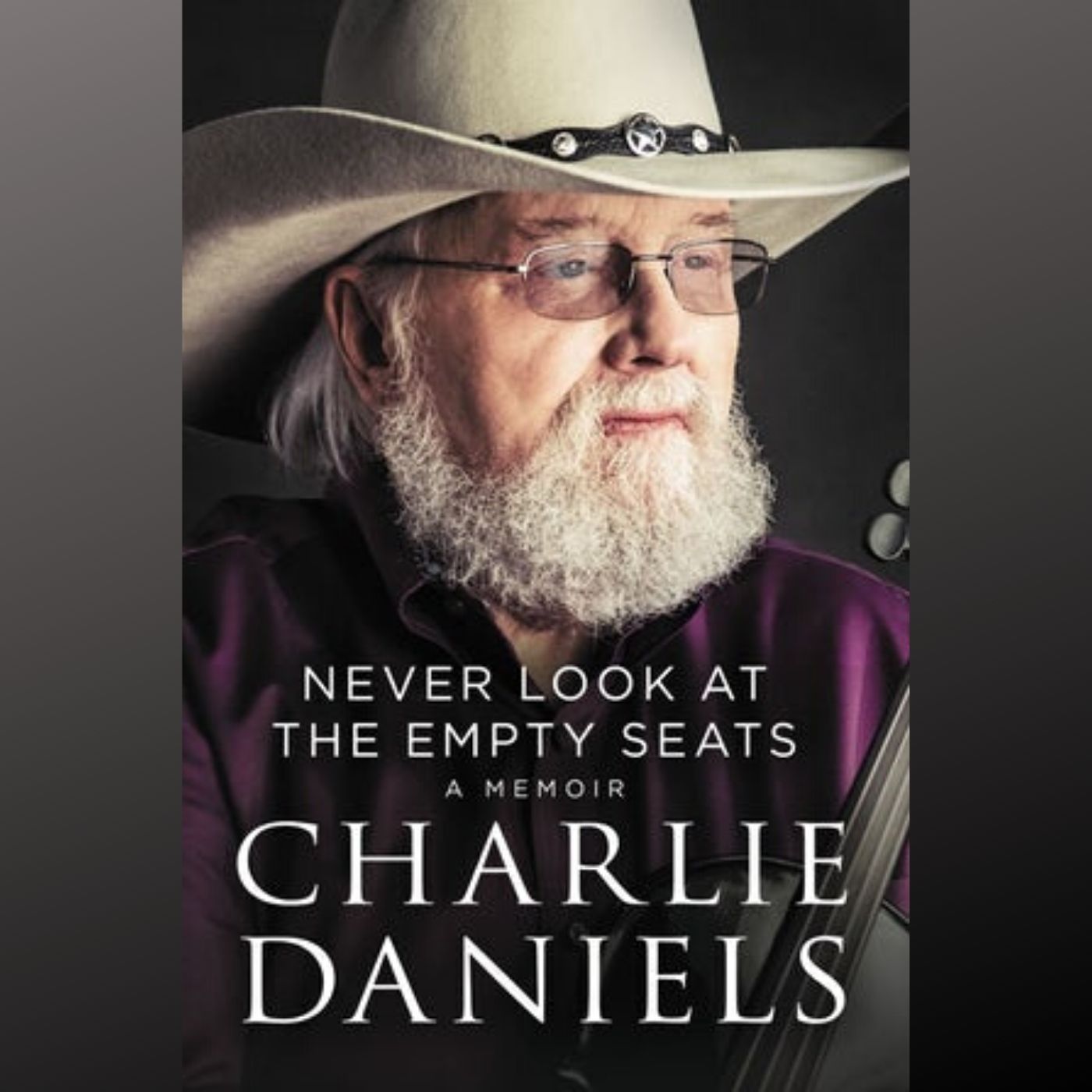

In 2017 Daniels gave his fans a firsthand glimpse at his life in his autobiography Never Look at the Empty Seats: A Memoir (Thomas Nelson). Daniels tells every tale in the book with a twinkle in his eye and a plainspoken delivery. He holds our attention by keeping the stories short — there are 63 chapters in the book, most of them about 5 pages long — and moving along at an easy pace. He regales us with tales of his childhood and youth in North Carolina. He recalls, for example, that he developed his love for singing early in life. One Wednesday night his father was attending the prayer service at the Holiness church across the street from Daniels’ grandmother’s house. When eight-year-old Daniels heard the congregation singing “Power in the Blood,” he “joined in by singing at the top of [his] lungs. ‘Oh, would you be free from the burden of sin? There’s power in the blood, power in the blood.’” Daniels recalls that “I was swinging and singing along with all my might when I saw my daddy come out of the church and make a beeline across the street” because everybody in the church was turning around to see who was singing so loud.

Charlie Daniels always spoke his mind, never fearing to call it as he saw it. His embrace of the National Rifle Association surprised many who knew him as the redneck hippie of “Uneasy Rider,” or the country singer who was an early supporter of President Carter. But 1978’s “The South’s Gonna Do It Again” embraced Southern cultural identity and raised the specter of nostalgia for the Lost Cause (the Civil War) and the possibility that this time the cause wouldn’t be lost. In his memoir, Daniels shares candidly his deep Christian faith, as well as his conservative political opinions, though he doesn’t ever reveal glimpses of the shift between the man who wrote that early hit and the man who made videos for the NRA. In a chapter titled “Heart of My Heart, Rock of My Soul, You Changed My Life When You Took Control,” Daniels ponders the depth of his faith and the simplicity of his conversion experience. There’s little room for argument in his words: “You have to repent, which simply means turn away from, change directions. … Jesus said He is the way, the truth, and the life. No man comes to the Father except through Him. He did not say a way, a truth, or a life. He said the way, the truth, the life.”

In a chapter titled “Ain’t No Fool Like an Old Fool,” Daniels moves quickly from one idea to another, all connected by his desire to express his opinions on topics from the Second Amendment to corrupt politicians to climate change. He points to his website’s “Soapbox” column in which he discusses everything from current events to going shopping with his wife. For him, this offers a forum for expressing himself as a “private citizen.” “I don’t believe in using my time onstage for anything but entertaining the paying customers. I restrict my personal political convictions to interviews and columns,” writes Daniels. In this chapter, for example, Daniels writes that he has “rock-solid convictions about the Second Amendment and fully believe that US citizens have a constitutionally ensured right to keep and bear arms.” And, “I have nothing but personal disdain for politicians who put personal gain above the good of the country.”

Reading these chapters might make some people who know Daniels only through his music uncomfortable, but they also offer glimpses into Daniels’ larger-than-life personality. In his interviews, and in the memoir, Daniels tends to separate the music, though. The memorable moments of the memoir come when he writes about what he’s learned on the road, in the studio, and on the stage. In the early 1970s, after he cut his first album and was traveling to promote it, Daniels learned a lesson about building a following: “I’ve always subscribed to the theory that if you can’t get what you want, take what you can get and make what you want out of it, and we tried to make the best situation we could out of whatever we were presented with. If there are only twenty people in the place, you played for those twenty people. If what you do pleases them, they’ll be back and probably bring someone else with them. And it snowballs. That’s how you build a following.”

Toward the end of his memoir, Daniels shares the wisdom he gained over his 60-plus years in the music business: “Doing a medley of your better-known songs and spending the rest of the show trying to sell the crowd your new album is self-indulgent and unfair to the folks who bought the tickets”; “When you walk onstage, you have to leave it [anything that is bothering you] all in the wings; if you claim to be a professional, act like one”; “If you don’t have a fire in your belly and a heart so full of desire that you can’t imagine your life without a career in music, don’t even put your foot on the path because you’re going to get your heart broken.”

Perhaps his best piece of advice gives his book its title: “Walk on stage with a positive attitude. Your troubles are your own and are not included in the ticket price. Some nights you have more to give than others, but put it all out there every show. You’re concerned with the people who showed up, not the ones who didn’t. So, give them a show and … Never look at the empty seats!”

If you’ve been a life-long fan of Charlie Daniels, pick out your favorite Daniels’ albums and put them on the turntable as you listen to his voice though the words in his memoir. As in his life and music, Daniels tells it like he saw it and, for him, as it is. We see every side of Daniels, who was never afraid of sharing his opinions with politicians, members of the military, and his fans. Reading Never Look at the Empty Seats, fans will learn from and enjoy Daniels’ wit and wisdom and discover why, as Aaron Tippin said, “He was an amazing man, musician, songwriter and entertainer.”