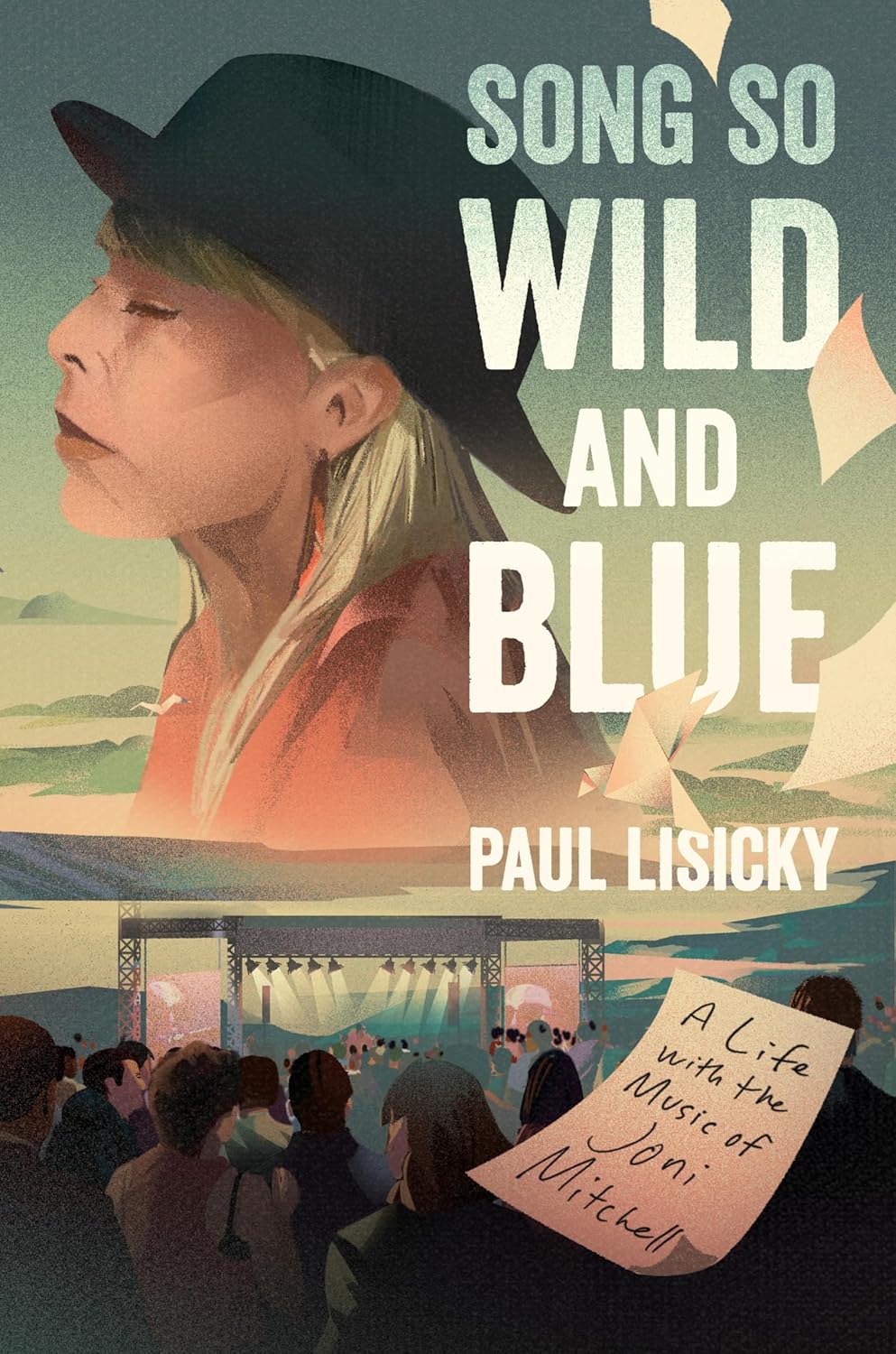

THE READING ROOM: Song So Wild and Blue: A Life with the Music of Joni Mitchell is Part Memoire, Part Critique

The songs of Joni Mitchell saved novelist Paul Lisicky’s life. In his loving ode to Mitchell and her music, Song So Wild and Blue: A Life with the Music of Joni Mitchell (HarperOne, February 25), the novelist declares that in these reflections he “wanted to give to others what Joni had given to me, which was more than a sequence of brilliant albums. Her work had given me a chart as to how one lives a life, evolving over time, rejecting a previous self, trying out a self simply through a new palette of tunings, keys, instruments, and washes of sound.”

Part memoir and part music critique, Lisicky admits from the start that he didn’t set out to write a biography; rather, in these pages he meditates on the ways that Mitchell’s songs accompanied him through his coming-of-age, especially as he shaped his own craft first as a musician and a songwriter, and then as a novelist and memoirist.

Lisicky first discovers Mitchell’s music when his fourth-grade choir director, Mrs. Hill, introduces the chorus to Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now.” Although the chorus generally sang upbeat songs such as “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” and “Let the Sunshine In,” he noticed right away the difference between Mitchell’s song and the others: “It sounded happy on first listen, but on closer inspection, heartbroken at the same time. The person who had written it had lost things, I felt that, but the source of that sadness was deeper than merely growing up, changing, leaving a house and a hometown behind.”

After this encounter with Mitchell, Lisicky, who had been learning piano, decides to drop the piano and pick up the guitar, and he eventually takes up songwriting. He admits, though, that he never achieved the freedom Mitchell did in her music, for she “cracked open the staff and found new notes in it.” Perhaps these notes she found were present, he writes, but no one, including Lisicky, “had the imagination and drive to find them.” When he compared his own songwriting to Mitchell’s, he found that his own voice “sounded like soil when I wanted it so sounds like sky, cold and clear.”

In his late teens and early twenties, and still in the thrall of Mitchell’s vivid writing, but recognizing his inability to write a song as vibrant as Mitchell’s, Lisicky moved on from songwriting to writing prose. As he looks back on this shift in the book, he reflects on the depth to which his songwriting shaped his prose: “I’d come to think of my paragraphs as the sweet ghosts of my songs. I was a better writer for pulling in what I knew about phrasing, unexpected chordal leaps, shifts in meter, changes in emotional register, the silence between notes. Every writer should begin with another art form—acting, painting, sculpture—and use that as a point of comparison or departure.” In addition, Lisicky writes, “I’d think of my stories as songs, long songs that needed to go all the way to the right margin. My songs needed a page rather than staff paper for now. That was where I’d begin, which is not to say I didn’t at times think it was all a delusion. I’d keep my musical life unlived as a way to protect it.”

In some of the highlights of the book, Lisicky sprinkles reflections on Mitchell’s songs and albums throughout his memoir. For example, The Hissing of Summer Lawns, he observes, “felt cinematic, or rather like a series of short movies in which Joni played the various roles that made this image possible, which was why it didn’t feel narcissistic. There was something here. … about ennui, emptiness, surfaces, traps, lies, secrets, violence, oppression, willed forgetfulness, racism, the brutality and arbitrariness of America … There was a tension between the polished surface and the rawness of the lyrics, as well as with the restrained chaos in them.”

In his own prose writings, Paul Lisicky wants to give others what Joni gave him: “more than a sequence of brilliant albums.” Her work gave him “a chat as to how one lives a life, evolving over time, rejecting a previous self, trying out a self simply through a new palette of tunings, keys, instruments, and washes of sound. . . .The body of her work was the body of a landscape. . . .And you couldn’t think about the work as a whole unless you were thinking about how each part talked back to the entire landscape.”

Song So Wild and Blue, Lisicky’s deeply adoring fan’s notes to Mitchell, will resonate with lovers of Mitchell’s music whose own lives have likely been as deeply shaped in similar ways by her music.