THE READING ROOM: Stepsister Offers a New Look at Robert Johnson

All rights reserved, cover courtesy of Hachette Books

Over the past few years, a few writers have been down to the crossroads of art and commerce to try to find Robert Johnson, amid especially contentious conversations about the few photographs we have of the legendary bluesman. Last year, Bruce Conforth and Gayle Dean Wardlow published what has been hailed as the definitive biography of Johnson, Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson, a meticulously detailed and thoroughly researched study by two authors who have spent countless hours in the Johnson archives and years interviewing people who knew Johnson. Zeke Schein’s Portrait of a Phantom: The Story of Robert Johnson’s Lost Photograph set some of the Johnson world abuzz by publishing his discovery of a photograph purportedly of Johnson that would be only the third known image of him. Although others question the authenticity of Schein’s discovery, his book is as much an affectionate tribute to Johnson as it is the story of how he came upon the photo while scrolling through the “old guitars” section of eBay in 2005.

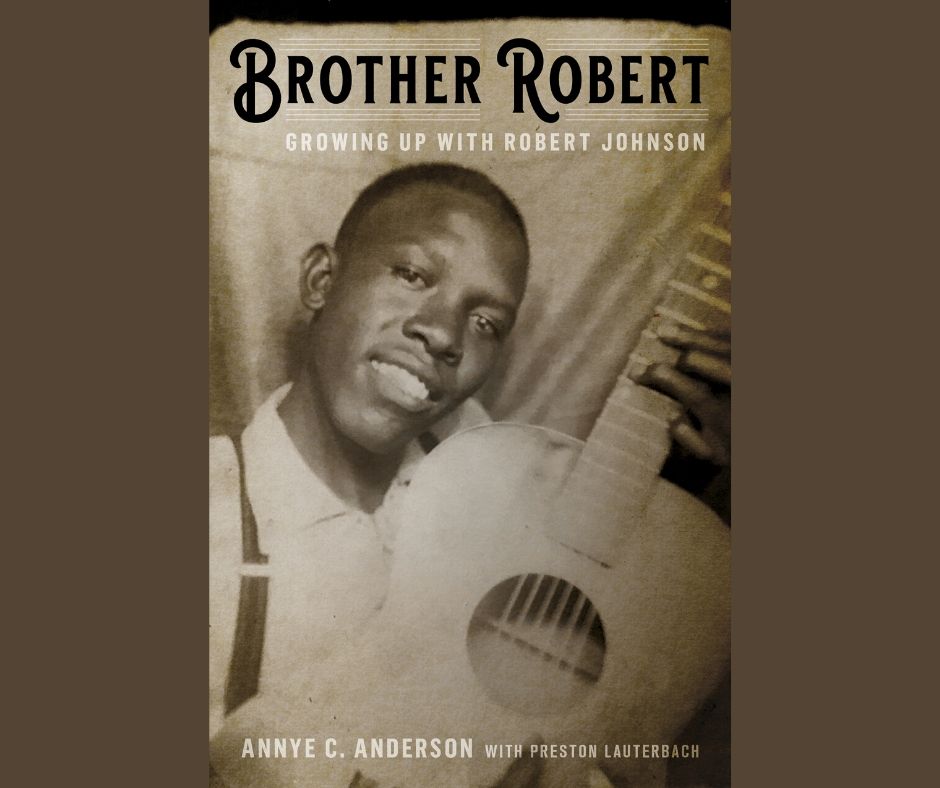

Now we have another perspective on Robert Johnson that adds new dimensions to our portrait of him and challenges some of the legendary stories that have developed around him and his music. In her intimate and warm Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson (Da Capo), Johnson’s stepsister Annye C. Anderson, in conversation with journalist Preston Lauterbach, recalls her life with him and provides stories of man she didn’t know primarily as a musician but as a loving, kind person who loved Gene Autry and westerns, Jimmie Rodgers, Buck Jones, Mae West, and Errol Flynn.

The book’s lively opening paints an endearing portrait of Johnson, offering a glimpse not of a tortured soul desperate to sell out to the devil for a bit of sweet music but of a loving brother: “I called him Brother Robert. He called me Baby Sis or Little Girl. We weren’t blood. We were family. First time I remember Brother Robert, he helped us move to Memphis from the country in 1929. My little legs couldn’t make it up the big staircase leading to our new house. I felt someone scoop me up and carry me. On his long, lanky legs, he took those steps two at a time. From then on, he was around sometimes for the rest of his life.”

Anderson shares her anger at the ways two musicologists — Steve LaVere and Mack McCormick — deceived her stepsister, Sister Carrie, and conned her family out of money and family photographs by making promises they never kept. “I understand that Steve LaVere has gone on, and Mack McCormick, too. But there are others and always will be: white men who don’t know us and think they own us. Steve LaVere may be resting in a golden casket that Brother Robert bought him.”

In addition to sharing stories of her beloved Brother Robert, she wants to debunk some of the stories that have gathered around him: “I felt like I had to protect the real Robert Johnson that I knew. He didn’t get his abilities from God or the Devil. He made himself. People have stuck Brother Robert’s family off to the side, because it makes him more interesting to be a vagabond or a phantom. And it makes him easier for someone else to make money off of if we’re out of the picture.”

The pre-publication conversation around the book, of course, concerns the photograph of Johnson (which is on the book’s cover) that Anderson has held onto all her life. It’s one more photo we have of him, but she makes very little of it in the book, and it’s not at all the point of her book. However, she tells the story of the photo in the last few paragraphs, leading to her recollection of her brother: “There is a make-your-own-photo place on Beale Street, near Hernando Street. … The photo place was right next door to Pee-Wee’s, the bar where Mr. Handy wrote his blues. One day when I was ten or eleven years old, I walked there with Sister Carrie and Brother Robert, I remember him carrying him carrying his guitar and strumming as we went, … I had my picture made. Brother Robert got in the booth, and evidently made a couple. I kept Brother Robert’s photograph in my father’s trunk that sat in the hallway of the … house while we lived there with my mother after my father died. After my mother died, we could only take so many things. I took my photographs with me, wrapped in a handkerchief. … I stored the photograph. … I have always had this photograph.

“It shows Brother Robert the way I remember him — open, kind, and generous. He doesn’t look like the man of all the legends, the man described as a drunkard and a fighter by people who didn’t really know him. This is my Brother Robert.”

Brother Robert includes a warm interview between Anderson and music historian Elijah Wald (author of Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues), as well as Lauterbach’s own sketch of “Brother Robert’s Beale Street.” Anderson’s a charming storyteller, and her stories provide a fresh perspective from which to see Johnson. Anyone interested in Robert Johnson will want to read her book, and it’s also likely to provoke some conversation in the world of Johnson studies.