THE READING ROOM: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers’ ‘Brothers and Sisters’ Era

Alan Paul has done it again. In 2014, he published a definitive oral history of the Allman Brothers, One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. While that book covered much of the history of the band, his expansive and captivating new book, Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined the ’70s, takes a closer look at the years between 1971, the year Duane Allman died, and 1976, the year the band broke up.

The pinnacle for the band in those years was the release of the album Brothers and Sisters, which contained the band’s hits “Jessica” and “Ramblin’ Man,” in 1973. Drawing on many never-before published interviews and other archival materials, Paul offers an illuminating glimpse at the rise and fall of a band whose music influenced so many other bands and launched a style that became known as Southern rock.

Paul also draws on interviews from Allman Brothers photographer Kirk West. “Kirk was researching a book while the band was broken up in 1986 and 1987 and he interviewed all the surviving members extensively: Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Jaimoe and Butch Trucks, as well as many other friends and associates,” he writes. “The subjects were talking to someone they deeply trusted, the band was twice broken up with no plans to reunite and everyone was bracingly honest and deeply reflective and insightful. The interviews were an absolute gold mine, most of which not even Kirk had ever listened to.”

Two years later, in 1971, just as the band was reaching new heights with its live album At Fillmore East, tragedy struck and Duane Allman was killed in a motorcycle crash. One year later, bassist Berry Oakley also was killed in a motorcycle crash, and the band found itself casting around for direction.

“There was plenty of musical talent to go around, and Duane had been the rare band leader who was neither singer nor songwriter. The band could work around the musical hole Duane’s death left, but it was going to be far more difficult to replace his leadership, which was natural, not forced,” writes Paul. “His bandmates followed Duane without his ever having to ask, and his presence provided an emotional equilibrium, no matter how wild his or anyone else’s behavior became.”

Dickey Betts, whose “distinctive melodic lines led him to consistently come up with memorable lines, which Duane jumped on,” stepped into the void, and the composition of the band started to change. Keyboardist Chuck Leavell had been playing with Gregg Allman on Allman’s solo album Laid Back and jamming with the Allman Brothers Band. Although Leavell was unaware of it, Allman had suggested adding him to the band. Writes Paul: “The pianist’s musical imprint is unmistakable on the first two tracks the band recorded, Gregg’s ‘Wasted Words’ and Betts’ ‘Ramblin’ Man.’ He added a bounce that elevated ‘Wasted Words,’ undergirding Betts’ slide guitar, which was less fluid and expansive than Duane’s and more attuned to playing a defined melodic part.” Lamar Williams joined the band as bassist, and the new incarnation of the Allman Brothers Band was complete. In 1972, “the Allman Brothers Band was entering a new stage,” Paul writes. “While it felt good to everyone, no one could have anticipated just how smooth the transition would be or how successful the new iteration would become. That success was being worked out in real time on stage and in Capricorn Studios, as Lamar and Chuck settled into their roles.”

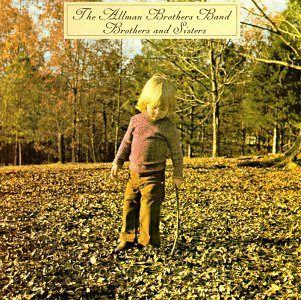

As it turns out, of course, the band experienced some of its greatest success with Brothers and Sisters. While the band didn’t always get along, and while there were difficulties with management and with the Capricorn label for which they were recording, the band had come together in the wake of its losses and was playing some of its best music. The album cover reflects the moment in the band’s history: “For all the turmoil that existed in the Allman Brothers Band and all that was soon to come, the album title and photos captured the reality of the moment,” Paul writes. “The band had rallied together in the face of tremendous loss; they had pulled together in a family bond and created more art in the spirit Duane intended. But, like most things in the Allman Brothers Band world, nothing was ever as easy or straightforward as it looked in the Brothers and Sisters gatefold.”

Just two years later, in 1975, the band released Win, Lose or Draw, and it was the start of the end of the halcyon period. “The main problem with Win, Lose or Draw is simply that none of us were really into the music,” [Butch] Trucks said. “The thrill was gone and we quit surprising each other. It just wasn’t fun anymore. When we heard the finished music, we were all embarrassed.”

“And so,” Paul writes, “the Allman Brothers Band broke up. The end came without an official announcement, a big fight, or a final tour or farewell concert. Instead, the band ended by publicly disparaging each other in print. Just two years after being the country’s most popular band, rising from the ashes following Duane and Berry’s deaths, the Allman Brothers Band just kind of fizzled away. Capricorn publicity manager Mike Hyland said that ‘there was no chance of the band getting back together.’ They were no more.”

Paul concludes: “It’s an odd fate for the years when the Allman Brothers Band elevated above their rock and roll peers to become an American institution, the most popular band in the country, a group that birthed a genre, had immense impact on country music, helped elect an American president, and stood at the center of the nation’s culture — a band that really, truly mattered.”

Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined the ’70s captures a classic moment in rock history, and with his riveting writing Paul tells compelling stories that make his book essential reading for Allman Brothers Band fans and for all fans of rock music.

Alan Paul’s Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined the ’70s will be published by St. Martin’s Press on July 25.