THE READING ROOM: The Man and the Album That Uplifted Live Gospel Records

Anyone who’s seen Amazing Grace, the film of Aretha Franklin’s performance of her 1972 album of the same name, knows James Cleveland. He’s the tireless master of ceremonies and pianist and singer. More than that, he lifted Franklin up, encouraging her and doing what he had already done so successfully since the early ’60s: bringing live recordings of African American gospel music to a wider audience.

Last month, gospel historian and critic Robert M. Marovich published The King of Gospel Music: The Life and Music of Reverend James Cleveland via Malaco Music Group. Marovich’s appealing book is not a definitive biography of Cleveland, but it provides a detailed biographical sketch of Cleveland, from his youth singing in Thomas A. Dorsey’s choir in Chicago to his own extensive work with quartets and choirs including The Gospelaires, The Gospel All Stars, The Caravans, The Chares Fold Singers, and The Southern California Community Choir. Marovich draws on extensive interviews with Cleveland’s family, friends, fellow singers and musicians, and others, as well as material from Cleveland’s archives, to tell the story. The King of Gospel Music is accompanied by four CDs that provide the sonic contours of Cleveland’s musical journey. Marovich provides overviews of every song on these CDs, allowing the reader to trace Cleveland’s musical development over 40 years, from his first recording in 1951 to his last in 1991.

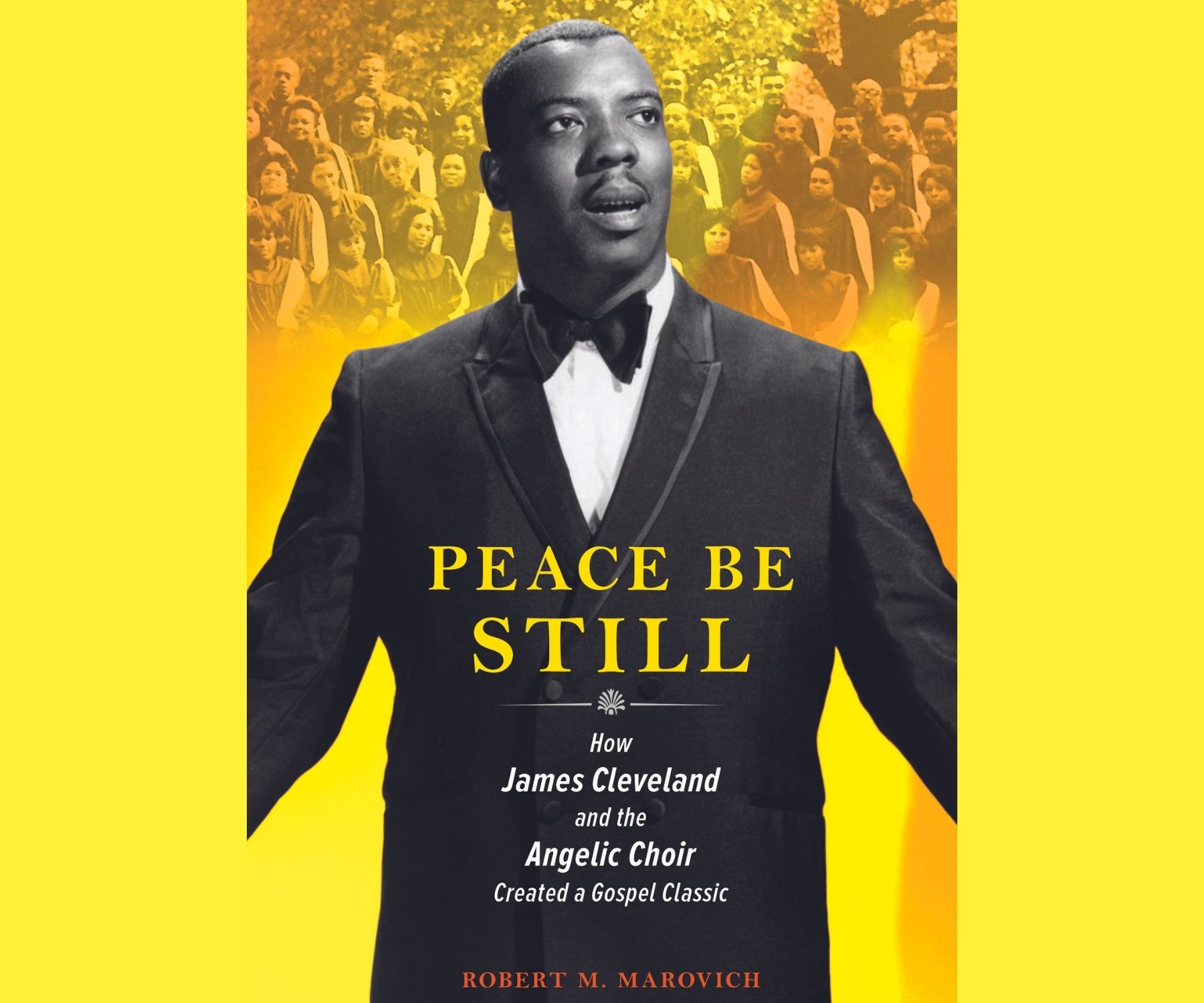

One of the songs on the first CD in The King of Gospel Music set is “Peace Be Still,” which is also the title track of Cleveland’s best-known and best-selling album. While Marovich focuses on the larger context of Cleveland’s life and music in The King of Gospel Music, he devotes his new book, Peace Be Still: How James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir Created a Gospel Classic (Illinois; out Nov. 8), to a long-needed exploration of the album and the song.

Peace Be Still, the album, was the third volume of the early 1960s collaboration among the First Baptist Church of Nutley, New Jersey; Trinity Temple Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Newark, New Jersey;, and James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir. The first two albums were recorded on Sundays at the First Baptist Church, as Marovich points out, when the “spiritual residue of a morning of soul-stirring worship could bleed into the afternoon’s recording session.” When the time came to record the third volume — which would become Peace Be Still — on Thursday, Sept. 19, 1963, the First Baptist Church was no longer standing, so the session was relocated to Trinity Temple, and musicians had to be found to replace organist Billy Preston and choir director Thurston Frazier. Those early moments didn’t augur well for this third volume to be released, like the first two, on Savoy Records.

In spite of Savoy’s devoting little marketing effort to the album, it rose quickly in early 1964 to the top of Billboard’s Top Spirituals charts, staying there for almost two years. Marovich observes that the way the album was made changed the recording of African American gospel music, an influence that endures even today.

“Although it was not the first African American gospel recording to be produced in a church and in front of a live audience or congregation, Peace Be Still is frequently credited as having given birth to the live recording era in African American gospel music because it was the first such album to achieve stupendous sales figures. Today, many African American gospel artists prefer to record in a live worship setting with an enthusiastic congregation for their audience … Peace Be Still even altered the way record companies conceptualized long-playing gospel albums. No longer were they haphazardly programmed collections of radio singles and fillers — they were developed deliberately to disseminate a live in-service experience that could transcend denominational, cultural, and spatial boundaries.”

With deft close listenings, Marovich offers in-depth reflections on each song on the album. For example, the album’s opening track, the 10-and-a-half-minute “Jesus Saves,” “was among the longest gospel song presentations committed to vinyl by that point. The length gave listeners unfamiliar with the rhythm and spirit of African American gospel music a chance to hear the dramatic ebbs and flows, the dynamic peaks and valleys, play out over a period longer than radio play permitted. It also demonstrated a technique now ubiquitous in gospel music, of starting a selection by singing in a subdued manner, then building the song’s intensity to an emotional climax, and liberating the tension through a gradual cooling down to the conclusion.”

The title track, “coming as it does after the alternately relaxed and rollicking ‘Jesus Saves,’ signals that the mood is about to change. The opening is sweetly somber … the song fades to an end peacefully, calmly, the wind and the waves having subsided.” According to Marovich, “Peace Be Still” “is spectacular sacred theater. It raises gospel music to new heights of artistic accomplishment … James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir foretell the coming of the contemporary gospel music movement six years before Edwin Hawkins’s ‘Oh Happy Day’ made the transition official.”

Peace Be Still, the book, captures the exhilarating highlights of the making of this influential gospel, illustrating why James Cleveland deserves the title The King of Gospel Music. Marovich’s illuminating analyses serve as a brilliant introduction to Cleveland and his music, as well as to the ways that the album Peace Be Still changed the world of gospel music.