THE READING ROOM: The Rise of Chuck Berry and Rock and Roll

Chuck Berry’s straight-ahead bluesy, rhythmic romps “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Johnny B. Goode,” and “Maybellene” lie deep in the DNA of American popular music. A savvy entrepreneur, Berry cannily cashed in on the shift in musical styles from rhythm and blues to even looser, more spontaneous songs about cars, women, and lust.

Berry also took advantage of what rock promoter Alan Freed referred to as a change in audiences. In 1949, Jerry Wexler used the phrase “rhythm and blues” to describe what had been formerly called “race” music. Around that time, though, Bo Diddley, according to author RJ Smith, “was turning domestic appliances into guitars, and Wexler noticed how white kids were getting interested in R&B.” Freed came along and coined the term “rock and roll” to pronounce the shift in audiences. According to Freed, “What determines a particular demographic or a particular market is not who plays the music now or who sells the music, it is who buys the music … So-called rhythm and blues was bought by black people. It’s an unfortunate truth of merchandising in a free enterprise society that you need to target your audiences.”

In the fall of 1955, when Berry released “Maybellene,” he launched rock and roll into the stratosphere, his guitar providing the jet fuel for the liftoff.

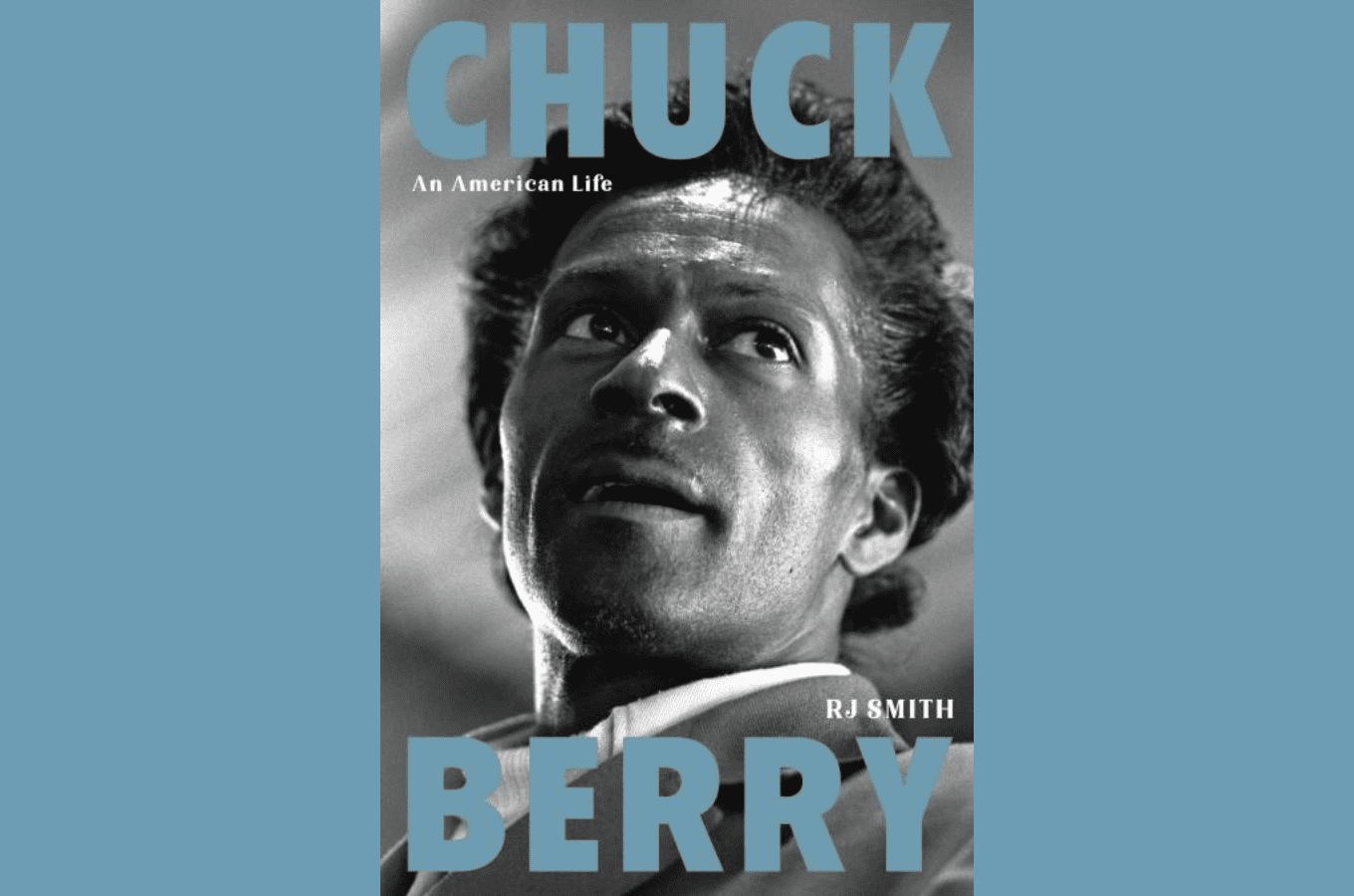

Smith’s absorbing new biography, Chuck Berry: An American Life (Hachette), provides not only a detailed, chronological account of Berry’s life, but also, more importantly, a compelling look at Berry’s artistry and a glimpse of American culture and how Berry responded to it, fit into it, or rejected it.

“Before he came along, rock and roll was a verb, a suggestion of sex and body, the blues-based words paired as opposites, gasping and sighing, committing and giving way,” Smith writes. “Chuck Berry turned that verb into a thing unto itself. Within months of the release of his first single, ‘Maybellene,’ people were using rock & roll in their daily conversation. The words explained what music they liked, then it expressed what in life they liked, and then it was them.”

Early in his career, Berry and his band absorbed and delivered to their audiences a blend of country, blues, and rhythm and blues. Berry grew up in St. Louis listening to country music on the radio and added songs such as “Jambalaya” and “Mountain Dew,” as well as songs by the Louvin Brothers and Kitty Wells, to his shows. Berry was ever attentive to his audience and the kinds of music people were listening to on the radio, Smith observes. Berry started out by thinking about audience in an “almost mechanical way: play music for more people, find out what they want to hear.” As Berry’s musical style evolved, he recognized that “key to getting a song over was positioning himself in various cultural traditions, and it started, he said, with his voice, the sounds of words and the weight he put on them and where they fell around the beat,” Smith writes, sharing this quote from Berry himself: “It was my intention to hold both the black and white clientele by voicing the different kinds of songs in their customary tongues.”

Berry thought of himself primarily as a performer, and his songwriting flowed out of his playing music. Smith peels back the layers of Berry’s process of writing songs, especially early in his career. Much of this was revealed in 2002, when Berry, who died in 2017, was a party to a legal dispute in which he had to detail his process. Smith writes: “Berry explains that they [he and his band] were kicking around a ‘simple’ rock & roll style that fit different songs, a consistency that one might liken to a groove. After they had established a way of working with each other, and then working to make songs together, the process wasn’t about bringing in a finished tune and pruning it like topiary. It was about playing with everybody throwing ideas in, seeing what each player’s style did to change what was thrown in. Berry strongly suggests that songs like ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ and ‘Johnny B. Goode’ came out of this collective process.”

The centerpiece of Smith’s book, though, is its emphasis on Berry’s deep love and identification with cars, illustrating that Berry’s desire for cars reflected his perception of success. So central were cars to Berry’s life and music that Smith opens his book with lines about them, returns to the topic throughout the book, and closes the book with a reference to cars. In the book’s opening paragraph, Smith writes: “Chuck Berry didn’t say much about cars to writers, who didn’t ask much about them. Little mattered more. They were a way to present himself to the public as he chose to be seen, and a way to hide from those he did not want looking at him. Cars were a sign of his mastery of success; cars offered a way out. Cars, to Berry, were self-evident in their importance. He loved their surfaces, wrote songs about the freedom they made possible.”

Berry wrote several songs about cars, but “Maybellene” may be the best known. It was the first of what Berry called “the car songs,” writes Smith. Moreover, Smith notes, “Chuck Berry’s guitar was a tool, a contraption. His Cadillac was Chuck Berry. He showed off his first car registration to a visitor once, preserved in a scrapbook … ‘All you had to have was a car and a guitar and you could make it in the world,’ he said.”

For Smith, “Chuck Berry was one of the greatest makers of the twentieth century — literally, he was one of the key inventors of the era, because he didn’t just help make a thing that changed our lives; his conception, rock & roll, created a time. He helped create a hybrid music that had only existed in beta form before, and he made it connect across every conceivable border of American music.”

Smith’s compelling storytelling makes Chuck Berry: An American Life a real page-turner. He draws deeply on interviews — many with fans who saw Berry when they were teenagers —as well as archival research to provide a rich, passionate, and elegant portrait of that “brown-eyed handsome man” from St. Louis, Chuck Berry.