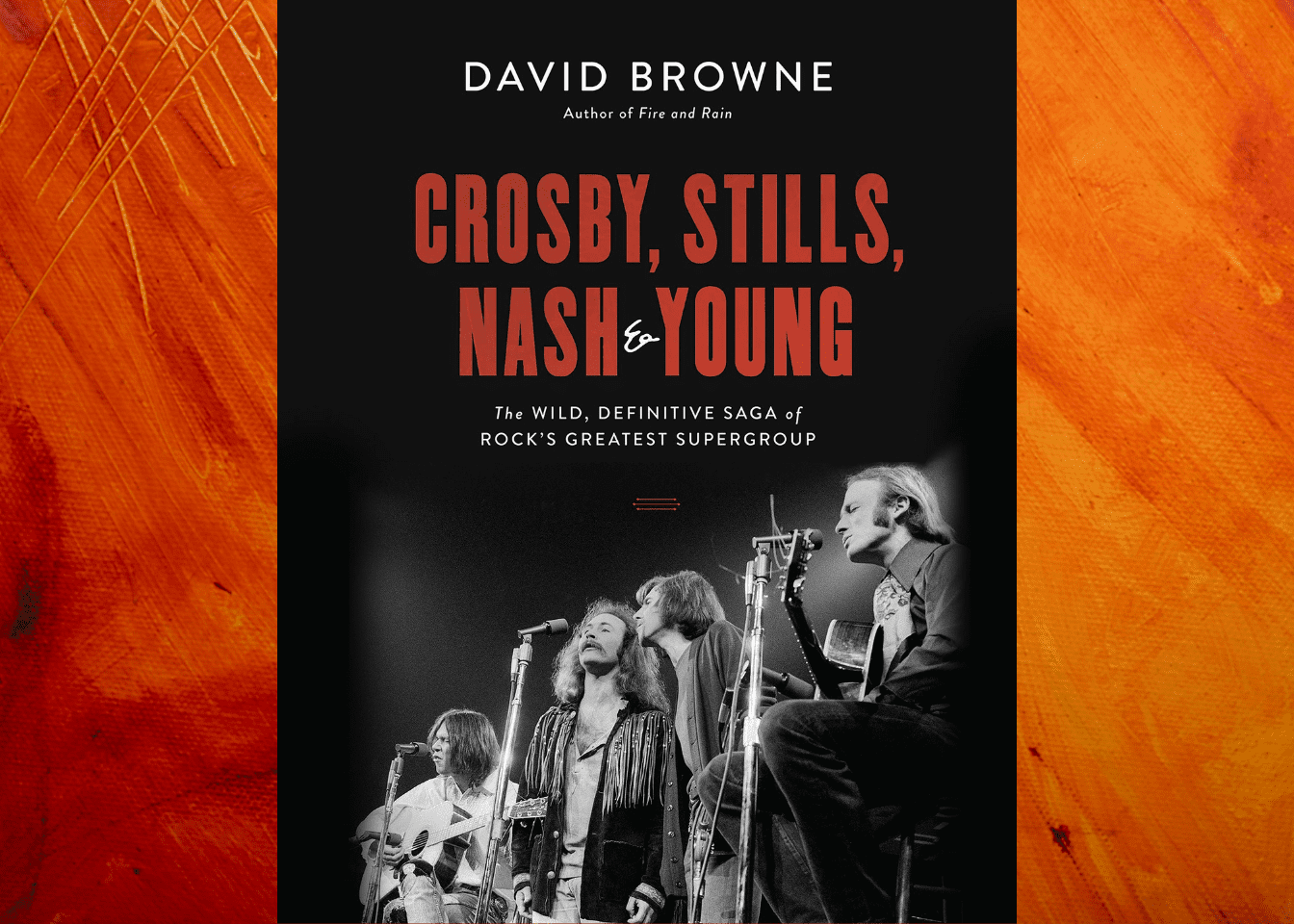

THE READING ROOM: The ‘Wild, Definitive Saga’ of CSNY

It’s a good year to be Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, probably even better than the short time they existed as a “supergroup” in 1969 and 1970.

Andrew Slater’s film Echo in the Canyon recalls the heyday of the idyllic musical Eden, Laurel Canyon, where the four musicians met up and honed their craft. The film features interviews with Stephen Stills, David Crosby, and Graham Nash. In addition, Woodstock turns 50 in a few weeks, and that festival both thrust the group before a large, though sleepy, crowd — they played at 3 a.m. on the festival’s final day — and marked the beginning of the end for the quartet. On that early morning at Woodstock, Stills famously declared: “This is the second time we’ve ever played in front of people, man, and we’re scared shitless.”

While each of the four is still releasing albums, many fans hold fast to the feeling that the individuals were never as good alone as when they were weaving their harmonies under and around each other; as solo artists, their output has been wildly uneven, though Stills, always underrated as a guitarist, has put together a blues band, The Rides, with Kenny Wayne Shepherd and Barry Goldberg, that rivals his own supergroup with Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield. Yet, as Graham Nash tells David Browne in Browne’s excellent Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young: The Wild, Definitive Saga of Rock’s Greatest Supergroup (released in April by Da Capo), “what a story; what a fucked-up foursome.”

Drawing deeply on archival material and on new interviews with band members, their colleagues, and friends, Browne tells a fascinating tale of artists searching for the lost chord, trying to find the right combination of voices and instruments, and developing briefly into a group whose most memorable songs — “Almost Cut My Hair,” “Ohio,” Woodstock,” “Teach Your Children” — became anthems for a generation dreaming of changing the world for the better with peace and love. Browne opens the book by recalling the first time he heard CSNY and his early “power-of-the-song moment” he experienced: “Using the songwriting credits as my guide, I was struck by the way David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and Neil Young each sang in a distinctive voice and had a songwriting style of his own, yet still managed to create a unified sound together. The lyrics had an unguarded directness I wasn’t accustomed to hearing in much rock at the time … with these people, their feelings of confusion, romantic anguish, or anger were entirely out in the open.”

It isn’t just the music that keeps us listening to CSNY, though; it’s also the mystique and the mythology. We’re just as interested in what happened in Joni Mitchell’s house with Nash, how Stills deceived Rita Coolidge and momentarily “stole” her from Nash, how Young always lurked around the fringes of the group, refusing initially to join them at Woodstock, or how Crosby was never afraid to let his freak flag fly to protest established political ways. As Browne puts it: “Crosby was the shoot-from-the-hip rebel who couldn’t help but stick it to the man. Stills, especially during his early years, was the driven careerist — always on the go, go, go — as well as the eternally wounded romantic who couldn’t always articulate his thoughts. Nash was the sensitive lady killer with the taste for quality possessions, the proto-yuppie. Young was the elusive, changeable outsider who couldn’t quite commit to any one thing at any one time.”

Browne develops the group’s story by focusing on each band member’s story and then weaving them into a seamless whole. In such a way, he can focus on the foibles of each artist even as he illustrates the ways those foibles often help create a strong fabric for the group. In the end, of course, the foibles are what tear CSNY apart. After their afternoon appearance at Altamont — where they played such a short set in the afternoon that most newspapers left them out of their coverage of the festival — CSNY, who had only been together as CSNY for less than a year, began their descent into disbanding. “Altamont was unlike any other show or event they experienced that year, yet, in a way, the bedlam of that day was of a piece with the crazy rush of the year they’d just endured. As Young noted later, ‘I could feel the music dying.’ Less than six months after they’d finished their first album and become a quartet, they needed a serious break from each other before the sea of madness finally engulfed them.” By 1971, the band split up; it came together only twice more to record as CSNY for 1988’s American Dream and 1999’s Looking Forward.

While we’ve all heard many parts of the CSNY story before, Browne’s persuasive storytelling keeps us moving forward, always eager to turn the page and read the details of the life and art of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young following their life in their short-lived supergroup. According to at least two of its members — Nash and Young — there will never be a reunion of CSNY, and that’s all for the good. In that one moment in late 1969 and early 1970, these four musicians came together and caught lightning in a jar, illuminating our musical and cultural landscape and revealing the power of song to move us toward change. The meticulous detail in Browne’s book provides the most wide-ranging and in-depth treatment we have of CSNY, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young: The Wild, Definitive Saga of Rock’s Greatest Supergroup ably lives up to the promise of its subtitle. Browne’s book also leads us back to the music and reminds us of the reasons that CSNY became the supergroup they became.