The Rolling Stones Cometh not with Peace but a Sword

by Matt Shedd

If you have not seen Gimme Shelter (1970), the documentary of The Rolling Stones 1969 tour culminating in the Altamont Free Concert catastrophe, I’d recommend it. If you need to be convinced: it’s a Criterion Collection movie, so you can be assured that your being enlightened as well as entertained. (Folks at Criterion, you can use that slogan if you’re reading this.)

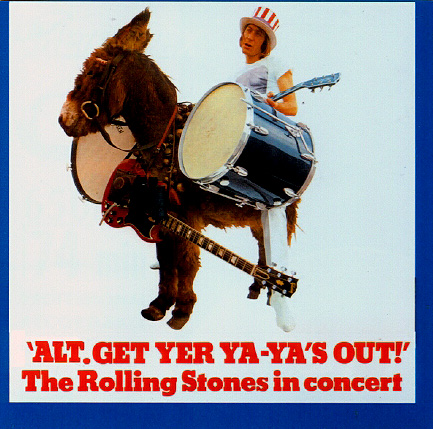

There are a great deal of things to say about the film, but I want to focus on the implications of the films opening images. Drummer Charlie Watts rides on a donkey, holding a rifle in his hand, and Mick Jagger frequently rushes on-stage wearing an Uncle Sam costume: a heavy-handed performance of his accomplishment. He believes he had conquered American music. Rock and Roll is something, the Americans and British have been fighting over since little Keef Richards heard Elvis the first time on his mom’s transistor radio. Rolling Stones have bragged about selling Americans their music back to them, and their hit covers were instrumental getting work for temporarily forgotten legends like Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry. In Rolling Stones: Stones in Exile (2010)–a highly recommended hour-length documentary about the recording of Exile on Main Street–Keith Richards states the band’s influences being predominately black American musicians. Richards lists Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, and Robert Johnson as important influences, a fact further evidenced by multiple covers of these artists’ songs.

However, we only need to look more closely at the band’s early records to see an American influence that spreads even wider than the expected blues and rock and roll acts. For instance, the US version of 1965’s Out of Our Heads is the album that shot the Stones to international superstardom, propelled by their first #1 hit “Satisfaction.” Also on the album are Marvin Gaye’s “Hitch Hiker,” “That’s How Strong My Love Is” made famous by Otis Redding, and Sam Cooke’s “Good Times.” The Stones didn’t just sell blues and rock and roll back to Americans, they repackaged soul and pop music, with hints of doo wop as well.

Returning to the opening image of Watts wearing an Uncle Sam hat riding a donkey and carrying a rifle, we see him masquerading as the quintessential American–one who spans all genres of its music and brings it to them from England. The image also can’t help but bring to mind the Christ one week before his crucifixion: “Fear not, daughter of Sion: behold, thy King cometh, sitting on an ass’s colt” (John 12.15, KJV). The absurd image of a rock and roll icon riding a donkey in costume registers with us for several levels. The Stones declare themselves kings, even messiahs, of American music. This British band can do it all: blues, rock and roll, soul–all genres that grew out of America–and they can do it better. This not-so-subtle suggestion is of course helped by the Uncle Sam costume and accompanying superhero cape. The opening becomes painfully ironic in the film’s violent climax between the Hell’s Angels and some very stoned hippies. So the image of the Stones entrance into America on a donkey was not as the Princes of Peace. It actually helped bring about the deaths of four devotee’s to the band’s music.

The Rolling Stones were tapping into a lot of violent aggressive energy at the time. They still do. That’s what makes them great–they’re music speak to those to human impulses whether your young or old, heard it then or now. The Altamont Speedway Free Festival took place December 6, 1969, the day after Let It Bleed was released. The band had been playing songs from the record throughout the tour as well. If the title isn’t suggestive enough of the violent energy the music captures, one doesn’t need to look too far for further evidence. The opening cut, “Gimme Shelter” refrains, “War, murder, it’s just a shot a way.” (Uncannily prophetic considering the homicide which took place at Altamont). Also on Let It Bleed, “Midnight Rambler,” a song from the point of view of a rapist murderer, contains the line, “I’ll stick a knife right down your throat.” (Ironically, the person murdered at Altamont was stabbed by a Hell’s Angel). Looking back at earlier Stones’ discography we find plenty of lyrics exemplifying the violence that occurred at Altamont. 1965’s “Playing with Fire” (“Don’t play with me because you’re playing with fire”) or 1966’s “Paint it Black” (“I look inside myself and see my heart is painted black…I wanna see the sun, blotted out from the sky”) are a few prime examples. In this way, the concert shows what happens when you get 300,000 people together, play with fire and paint everything black. The end of the sixties–a hippie dystopia.

Now I want to be clear that I am not taking a puritanical position regarding this songs. I love every above quoted song, and one cannot deny the dark human impulses they so brilliantly capture. Next time somebody tells me that Freud’s death drive doesn’t make any sense, I’m going to point them to “Paint it Black.” There were certainly songs just as violent in the blues tradition much earlier than this; listen to Robert Johnson’s “32-20” for a prime example. But that song for instance, was listened to on a phonograph or within a much smaller setting of a rural juke joint. I am curious as to what the Stones thought was going to happen when they gathered 300,000 drunk, stoned young people together, allow the Hell’s Angels to serve as security, and play a style of music that so perfectly captures our impulse towards rebellion and violence? Earlier in the film, Jagger un-ironically describes it not as a concert but “as an excuse for everyone, you know, to just sorta get together and talk to each other and sleep together and hold each other and get very stoned. And you know, just have a nice night out and a good day.” As the film bears out, people do sleep together and get very stoned, but the concert brings tragic results, far from merely “a nice night out and a good day.”

The donkey and the Uncle Sam hat at the film’s opening suggests the Stones vision of themselves to be simultaneously the embodiment and the messiahs of American music. Even if this is true, the message they bring is less related to any good news than it is to the rifle in Watts’ hand. The Stones bring not peace, but a sword. In short, I have not seen a better representation of what Taubin calls “the nail in the coffin of the 60s” (6) than Gimme Shelter. The aggressive energy of the Stones’ music ultimately destroys an Utopian visions of a sustaining the ideals of cooperation, free love, and non-violence the youth thought they had finally found at Woodstock.

The Rolling Stones. “Playing With Fire.” Out of Our Heads (US Version). ABKCO Records, 1965. CD.

Originally published:

A Missing America #1.

Fall, 2010.rit