The Story of Peg Leg Joe : carpenter, sailor and conductor on the Underground Railroad

Abstract :

Just as blues later, slave songs communicated messages and were often a cry of despair bathed however in hope. This article highlights the role played by one such a slave song, “Follow the Drinking Gourd”, in the guidance of the slaves on the road of hope and freedom which constituted for them the ‘Underground Railroad’. Peg Leg Joe was one of the conductors on this ‘Underground’ who is said to have made the road of many runaways to the North a success. But what is reality and what is myth? And if it was only a myth, why did it persist so long?

______________________________________

The train is a recurrent theme in many musical genres and particularly in the blues. The small town Tutwiler claims that the blues was even born on its train station platform where W.C. Handy reportedly for the first time heard the blues in 1903. Though Handy had heard something similar to the blues already earlier, it was while waiting for an overdue train to Memphis that he spotted an itinerant musician playing slide guitar and singing about “goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog”. The title referred to the junction of the Southern Railway and the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad farther south.

In the ornate language of the blues that draws heavily on images, the train has a major iconic value; not in the least it stood as a symbol for the escape to freedom first from slavery, and later from a bitter cocktail of Jim Crow laws and economic hardship. The railroad world has also given us a number of immortal (fictional and historic) figures in (blues) ballads as John Henry, who worked as a “steel-driver” in the construction of tunnels for railroad tracks, and Casey Jones who became a hero in a train incident when giving his life to protect to him unknown people. The tradition goes even further in time to the slavery times with the heroic deeds of a man name Peg Leg Joe, who was said to be a conductor on the Underground Railroad. This is his short story in its historical context.

We return to the decades before the Civil War. Approximately four million enslaved African Americans lived in the southern region of the United States of America. The vast majority of them worked as plantation slaves in the production of cotton, sugar, tobacco, and rice. Few of them were African born mainly because the importation of enslaved Africans was banned in 1808, although thousands were smuggled into the nation illegally during the following fifty years. National and international political pressure had fed the awareness that the institution of slavery had passed its heydays, which in many ways increased the tension in the race relations. The issue of slavery was rising to a boiling point, and the fragile harmony between slave states and free states was on the balance. I do not consider it a coincidence for instance that black face minstrelsy met with a rising popularity in the decades preceding the Emancipation Act. The lowering of ethnic groups is often a mere symptom of fear for a possible destabilisation of its own social position and power. Another sign of tension was that one of the clauses of the Compromise of 1850 – that installed a temporary solution for the nationwide disagreement on the future of slavery – was the strengthened Fugitive Slave Act that denied legal rights to any black person accused of being a runaway slave and that required all U.S. citizens to assist in the return of runaway slaves. A rigid social structure which had been self-evident during almost two centuries was being questioned. I can imagine that within the shackled black population hopes were fueled to be freed in a near future. It triggered a revolution of rising expectations.

It is safe to say that internal pressure and opposition to the bondage system within the slave population went hand in hand with those rising expectations. Resistance to the alienating system of slavery was not new. The day-to-day resistance took the form of for instance breaking tools, feigning illness, staging slowdowns and committing acts of sabotage. Slave uprisings – followed by hard and deadly repression, read mass executions – were another manifestation of resistance. An important number of slave rebellions took place in the first decades of the 19th century of which the Nat Turner’s insurrection is one of the most famous and deadly. The escape of slavery was a final way of turning its back to the system, and in the early 19th century it even was given a name: the Underground Railroad (1).

The Underground Railroad, which was at its height between 1850 and 1860, was a large network of people which helped fugitive slaves to get to the Northern (free) states of America or to Canada. The name was derived from the quick and secretive method that was used to escape. It was made up of many individuals — many whites, but predominantly black — who only knew the details of the local efforts to aid the fugitives without having an overall picture of the operation. They were organized in small, independent groups, which helped to maintain secrecy since only some knew of connecting “stations” along the route but otherwise would dispose of few details.

The escape organisation actually used railroad terms. The places (safe houses), homes and businesses – the Churches also often played a role – where the fugitives went to eat and rest were labelled “stations” or “depots.” They were spaced between 10 and 20 miles apart from each other. Those in charge of the stations were known as “stationmasters.” The escaped slaves were referred to as “passengers” or “cargo” and they obtained a “ticket” for the ride. The “conductors” accompanied the runaways from one station to the next .

The latter played an indispensable role in the functioning of the network. Their first step to get the slaves to freedom was to help them to escape from their slaveholders. To do so, a conductor would often pose as a slave and enter the plantation with all the risks involved. They moved by the darkness of night to the successive stations where the fugitives could eat, rest, and hide during the day.

The conductors came from various backgrounds and included free-born blacks, white abolitionists, former slaves and also native Americans.

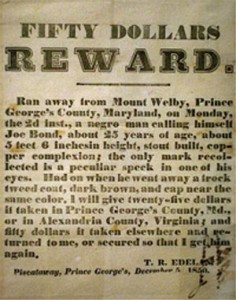

The primary means of transportation were on foot or by wagon. To mislead pursuers – federal marshals and professional bounty hunters (slave catchers) – routes were often purposely indirect. The conditions of escaping were very tough and hazardous. The slave owner put out rewards and had them published in newspapers and didn’t hesitate to put his blood hounds on the job.

The danger involved in this highly complex and secretive organisation required efficient means of communicating messages appropriate to the context, taking into account that slaves could mostly not read nor write. The messages needed to be coded and this happened in an aural and visual way.

Though there is still controversy over the subject, it is said that some messages were passed in the form of quilt patterns. “Most quilt patterns had their roots in the African traditions the slaves brought with them to North America when they were captured and forced to leave their homeland. The Africans’ method of recording their history and stories was by committing it to memory and passing it on orally to following generations. Quilt patterns were passed down the same way.” (Owen Sound’s Black History). Used in a certain order, the quilt patterns conveyed messages to slaves who prepared their escape. Different pattern represented different meanings. The quilts hung over a fence or in a window opening: it was a common sight on a plantation which didn’t draw the attention of the plantation owner or of the overseer. It is said that the stitching and the knotting contained secret information, map routes and the distances between safe houses. One example of a quilt pattern was the North Star which in fact is supposed to contain two messages one to prepare to escape and the other to follow the North Star bound to Canada, being the direction of traffic on the Underground Railroad.

North Star Quilt

This quilt signal was often used in combination with the song “Follow the Drinking Gourd”. Just as the quilts, songs were considered as a common, daily attribute of the slaves’ live, and were thus no element that would raise suspicion. They were the ideal vehicles by which slaves could pass messages between each other without it being noticed by the planter or the overseer.

Here comes Peg Leg Joe to the stage. The man was said to be a carpenter and a sailor who led slaves through the Underground Railroad to freedom. His name suggests he had a prosthesis. As a conductor of the Underground Railroad he is also credited for authoring the song “Follow the Drinkin’ Gourd”. What we know about the figure is based on the field notes by H. B. Parks – a Texas entomologist and an amateur folklorist – who states in 1928 that he overheard the song on a few chance occasions: first in North Carolina in 1912, then Louisville around 1913, and finally in Texas in 1918. His story was the subject of a conversation with an elderly man and his grandson in 1912 who remembered a one-legged sailor who “would go through the country north of Mobile and teach this song to young slaves and show them a mark of his natural left foot and the round spot made by the peg-leg.” H.B. Parks described the song as a “jerky chant”.

Later, in John A. Lomax’s 1934 book “American Ballads & Folk Songs” there is a quote of the story from H.B Parks:

“One of my great-uncles, who was connected with the railroad movement, remembered that in the records of the Anti-Slavery Society there was a story of a peg-leg sailor, known as Peg-Leg Joe, who made a number of trips through the South and induced young Negroes to run away and escape. … The main scene of his activities was in the country north of Mobile, and the trail described in the song followed northward to the headwaters of the Tombigbee River, thence over the divide and down the Ohio River to Ohio … the peg-leg sailor would … teach this song to the young slaves and show them the mark of his natural left foot and the round hole made by his peg-leg. He would then go ahead of them northward and leave a print made of charcoal and mud of the outline of a human left foot and a round spot in place of the right foot. … Nothing more could be found relative to the man. … ‘Drinkin’ gou’d’ is the Great Dipper. … ‘The grea’ big un,’ the Ohio.”

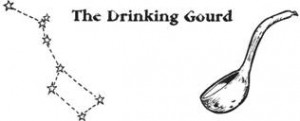

The song “Follow the drinking gourd” contains an amazing coded map and escape route in which the “Drinking Gourd” is nothing more than a reference to the Big Dipper star formation, which points to Polaris, the Pole Star, and thus to the North, i.e. the direction of free states and of Canada. The resemblance between the hollowed out gourd used by slaves and other rural Americans as a water dipper and the star formation cannot be ignored. The ‘Drinking Gourd’ was much more easily recognizable by the slaves than the Big Dipper.

When the Sun comes back

And the first quail calls

Follow the Drinking Gourd,

For the old man is a-waiting for to carry you to freedom

If you follow the Drinking Gourd

The riverbank makes a very good road.

The dead trees will show you the way.

Left foot, peg foot, travelling on,

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

The river ends between two hills

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

There’s another river on the other side

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

When the great big river meets the little river

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

For the old man is a-waiting for to carry to freedom

If you follow the Drinking Gourd.

As far as is presently known, it is the only song that contains a detailed map for the fugitive slaves. In 1947, an arrangement of the song was published by Lee Hayes, an American folk-singer and songwriter, who is best known for singing bass with The Weavers and also wrote or co-wrote “If I Had a Hammer” and “Kisses Sweeter than Wine”.

The story sounds fantastic and greatly impresses our imagination. What can built a greater story than quilts and slave songs that are used as detailed coded messages by heroic men and women who risk their own lives to help slaves on the road to freedom? Let us not forget that most slaves were uneducated and ill prepared for the long journey. Their escapes were as a rule not planned; it were decisions often taken on the spot taking advantage of favorable circumstances. “Follow the drinking gourd” was by the way not the only song that accompanied the slaves on their freedom route. A number of other songs have been associated to the Underground Railroad : “Go Down Moses”, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”, “Steal away”, “Song of the Free”, and “Wade in the water” (the latter being a tip for keeping the blood hounds off the track). The songs were also on the repertory of another notorious ‘conductor’, Harriet Tubman who after escaping herself from slavery is said to have made thirteen missions to rescue more than 70 slaves (those figures vary however from source to source).

But could this fantastic story be fantasized?

There is no doubt on the existence of the Underground Railroad or on the role that some people as Harriet Tubman have played in its success. A reliable source of information are the thousands of interviews done in 1936 – 1938 by the Federal Writers Project which recorded firsthand reports of slave life. These interviews have documented many escape routes, both on and off the Underground Railroad. However, doubts are raised as far as the existence of Peg Leg Joe is concerned for which there is no primary source material that certifies his factual role. Moreover, question marks are put next to the use of quilts and the use made of the song pointing the runaways to the ‘Big Dipper’. We also need to put the importance of the escape as a way of protest in a proper perspective.

As for the use of quilts, the idea of their role in the Underground Railroad for purposes other than bedding is not mentioned either in the written documents of the period or in the interviews given years later (Kris Driessen, Quilthistory). Though this does not imply that they could not have been used in any form, but it does tell us to be careful not to get too romantic. Quilt historian Xenia Cord contends: “Quilt research and quilt history often rely heavily on the oral anecdotes and oral memories of quilters, stories that link women with common interests to a body of shared information.” No hard evidence is at hand.

Just as the quilt history, the story of Peg Leg Joe is perhaps a way that allows a certain, romantic view on the past in the perspective of later objectives situated in another context. No written document exists that is conclusive evidence of the factual existence of Peg Leg Joe; on the contrary some authors argue that he was a composite figure, a fictional man that unified symbolically the actions of many others into one and the same person.There is indeed no solid proof, only anecdotal evidence, and of course, the song.

But the song itself may be a fabrication, since it has never been collected in Alabama, the alleged setting of the song. Some suspect that H.B. Parks made the song up. As Joel Bresler notes in “Follow the Drinking Gourd: A Cultural History”, “(H. B. Parks) accidentally hears three different versions of the song in an area comprising almost one hundred thousand square miles, while no one else appears to collect it anywhere.” (Craig Sanders, 2010).

The argument has also been put forth that the very nature of the song and its detailed geographical encoding is contrary to the basic principle of the Underground Railroad itself. The independent functioning of different ‘stations’ along the road, without somebody having a global overview of the route, was a key element to the success and would thus be in contradiction with the total map that is offered by the song. It is also hard to imagine that the version as we know it today could have been of much use to the people whom it was supposed to guide. Bresler (2008) carefully weighs the arguments in favour and against the probability of the reality of both Peg Leg Joe and ‘Following the Drinkin’ gourd’. He offers a new explanation to the history. If the song predated the Civil War, says Bresler, it could have served as an inspiration to escaping slaves. The song would initially have contained limited or no geographical information, this information being added only after the war. Another possibility is that the song as we know it from H.B. Parks emerged in its entirety after the Civil War. In this approach, the song is to be evaluated rather as folklore than as history.

Perhaps Peg Leg Joe might have been an actual abolitionist, continues Bresler, or a composite character. Perhaps the song really traces the route of one or several runaways and grew in popularity through the celebration of their exploits. We don’t know. According to Bresler’s alternative theory, the collectors could have heard the songs in the field and it could have been interpreted afterwards as folklore.

The reference to the Drinking Gourd and the Big Dipper furthermore creates the illusion that most of the escapes were headed north. Some sources quote that between 1840 and 1860 more than 30,000 Americans (some quote 300.000 !) slaves came secretly to Canada. Other sources point out however that the figures were much lower (Bresler, 2008) and that the phenomenon was, at least in the beginning, mainly located in the border counties in the Upper South. The escape from the Deep South would have seen roughly half of them direct towards the South (Indian Territory, Florida, Mexico and parts of the Caribbean) and not towards the Big Dipper. Running away from the Deep South states up to the north must have been a particularly hazardous undertaking, not only because of the distance but also because the planters were more careful about keeping their ‘property’ on their ground. The value of slaves had considerably risen since the international trade in slaves had been outlawed after 1807.

Successful escapes were moreover probably rare and candidates must have been aware of this. A fugitive knew that he would have problems of finding food and shelter in a hostile environment. Moses Grandy, born a slave in Camden County, North Carolina ca. 1786, describes the problems that runaways faced: “They hide themselves during the day in the woods and swamps; at night they travel, crossing rivers by swimming, or by boats they may chance to meet with, and passing over hills and meadows which they do not know; in these dangerous journeys they are guided by the north-star, for they only know that the land of freedom is in the north. They subsist on such wild fruit as they can gather, and as they are often very long on their way, they reach the free states almost like skeletons.”

Estimates of the number of slaves who escaped through the Underground Railroad vary enormously. Some quote a figure of 100.000 in the 1800’s; others conjecture that the number is more in the range of several hundreds or one thousand per year in the mid 1800s. One source puts forth a total of not more than 2.000 who in the period between 1830 and 1860 made use of the services of the Underground Railroad.

It has also to be considered that many escapes were geographically limited and did not go any further than the nearby city or natural refuge like swamps or mountains where the runaways formed communities (“maroon colonies”). Not all of them tried to permanently escape slavery. Running away was after all in the first place a form of resistance. It was also seen as a temporarily withholding of labor as a form of economic bargaining and negotiation over the pace of work, the amount of free time, and the freedom to practice burials, marriages, and religious ceremonies free from white oversight. It is also safe to contend that runaways were often relatively privileged slaves who had worked as river boatmen or coachmen and were familiar with the outside world.

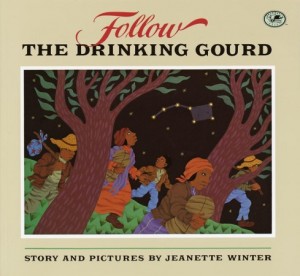

Why then has the story of Peg Leg Joe and the “Drinking Gourd” proven to be so persistent? We even see it pop up in a scene of Monty Python’s “Life of Brian” in 1979 where it is subject of parody (Follow the Sandal). It figures in the school text books in the United States. In 1988, author Jeanette Winter made the song the subject of a popular children’s book. The book formed in 1995 the narrative core of a planetarium show co-produced by the New Jersey State Museum Planetarium and the Raritan Valley Community College Planetarium.

As Craig Sanders (2010) e.o. point out there has been a link between “Follow the Drinking Gourd” and the Civil Rights Movement. Already early on in the movement, the song has been reworked by Lee Hays who altered the melody some and polished some of the local dialect to make the song more appealing to a larger audience. It was later on covered by many other artists during the the Civil Rights Movement: The Weavers, Pete Seeger, The New Christy Minstrels, Peter, Paul and Mary, and others. The song is a piece of American Music History, an icon, whether it is authentic or not. Through the song and through figures as Peg Leg Joe it was possible to depict the Underground Railroad and the fight of the blacks for their freedom. Both made the history more tangible and appealed to the imagination of the public. They were strong symbols which articulated the anger, despair, hopes, and the political struggle for freedom. The song and its supposed author Peg Leg Joe clearly illustrated that African Americans never accepted their fate and that their natural inclination was to be free.

For us, blues aficionados, the song is also a strong reminder of one of the basic characteristics of the blues idiom in which a song is a means to transcend reality, a cry of despair infused with a strong hope that at the end of the journey life will be better. It symbolizes the feeling of sharing the same fate and helping each other out to cope with that fate. In that perspective, the story of Peg Leg Joe and his ‘escape’ song crystallizes also a core element of the blues: the permanent hope to overcome the daily hardship of wearing the shackles of oppression and economic and social discrimination.

“Trouble in mind, I’m blue

But I won’t be blue always

‘Cause I know the sun’s gonna shine in my back door someday”

____________________________________

Footnotes:

____________________________________

(1) “It is not exactly clear when slave escapes came to be thought of as part of an “underground railroad.” According to one popular story, the phrase orginated when a slave named Tice Davids fled from Kentucky in 1831, probably taking refuge in Ripley, Ohio. The owner chased Davids in a rowboat as the fugitive swam across the Ohio River to Ripley, where he disappeared without a trace, leaving the bewildered slaveholder to wonder if Davids had somehow “gone off on some underground railroad.” The story spread among slaves and slaveholders throughout the country, fueling myths and hopes of escape via an “underground railroad.”

(quoted in : http://wordpress.georgetowncollege.edu/ugrri/research-and-resources/general-information/)

____________________________________

SOURCES :

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=79

http://www.followthedrinkinggourd.org/

http://www.followthedrinkinggourd.org/The_Song_As_History.htm

http://www.osblackhistory.com/drinkinggourd.php

http://wordpress.georgetowncollege.edu/ugrri/research-and-resources/general-information/

http://www.connexions.org/CxLibrary/Docs/CxP-Underground_Railroad.htm

http://craig-sanders.suite101.com/the-true-story-of-follow-the-drinking-gourd-a189775

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Songs_of_the_underground_railroad

http://www.schoollibraryjournal.com/article/CA6430152.html

http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20070508162807AAaHlO2

http://factoidz.com/coded-slave-songs-how-they-were-essential-to-the-underground-railroad/

http://www.osblackhistory.com/songs.php

http://www.bellaonline.com/articles/art35016.asp

http://docsouth.unc.edu/highlights/gospel.html

http://pathways.thinkport.org/secrets/music2.cfm

http://www.histori.ca/minutes/minute.do?id=10166

http://www.kimandreggie.com/steal_cd.htm

http://ethemes.missouri.edu/themes/988

http://www.quilthistory.com/ugrrquilts.htm