The Stories (and the Love) Behind Three Tony Rice Tributes

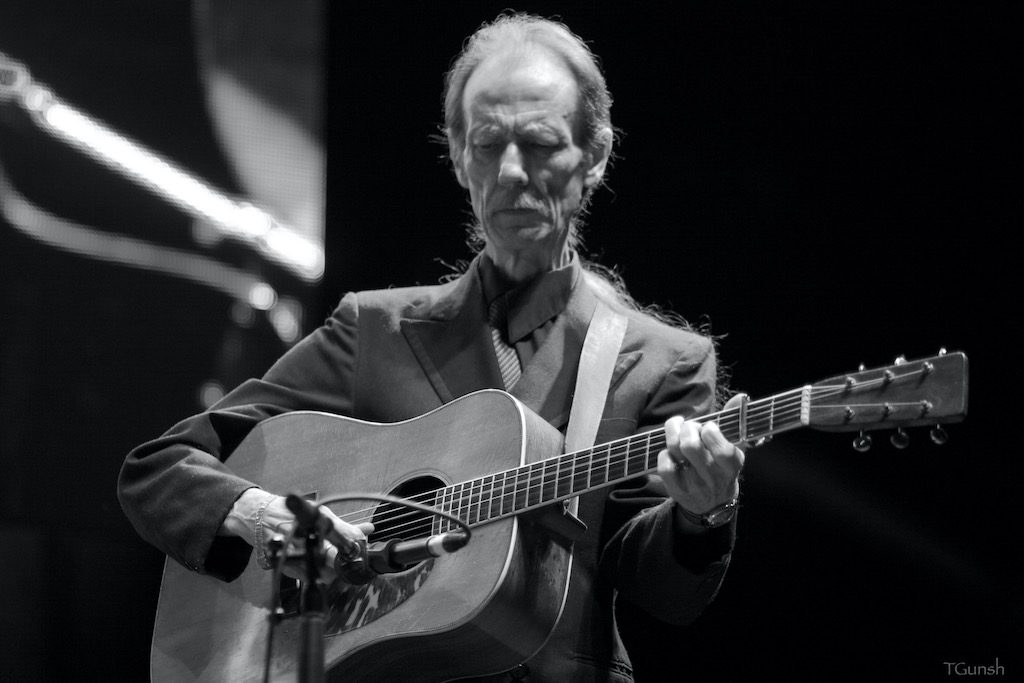

Tony Rice during the International Bluegrass Music Association's World of Bluegrass 2013. (Photo by Todd Gunsher)

Tony Rice was a master of his craft whose guitar licks have been copied by thousands of bluegrass and jazz guitarists. His rich, warm vocal tones also influenced singers in bluegrass and beyond. Most of all, Rice encouraged every musician he ever met, taking time to listen to their work and urging them to make their sound their own.

His death on Christmas Day in 2020 was devastating to his many fans and musical peers, but his influence lives on, as evidenced by the musical tributes in the works since.

Producer Barry Waldrep called in more than 21 musicians whose music had been shaped by hearing, and in some cases meeting and playing with, Rice for his project called simply Barry Waldrep and Friends Celebrate Tony Rice. Inspired by Rice’s music, his friendship, and his generous support of the band, Punch Brothers went into the studio in late 2020, before Rice died, to record Hell on Church Street, their reimagining of Rice’s classic album Church Street Blues. Bluegrass singer and guitarist Dan Tyminski wrote a song for Rice, his dear friend, as a way of grieving, and the song led to an EP coming later this year called One More Time Before You Go.

Rice may have started in bluegrass, but he edged into jazz and brought the flavors of Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli into the genre, and he pushed the envelope of flatpicking guitar so that guitar players in all genres find themselves playing licks they picked up listening to his work. Rice’s innovative and expressive guitar playing, his honest vocals, and his genius in finding and arranging songs, as well as his warm, down-to-earth personality, shaped generations of musicians. As John Cowan puts it: “Tony touched people well outside of the acoustic world. He was a genre-buster in a way. Rice’s contribution to music is gigantic.”

Rice’s musical journey is well known: a youth spent playing bluegrass, joining J.D. Crowe and the New South when he was 20, playing with David Grisman in his band in the mid-’70s, and incorporating elements of jazz and folk in his playing along the way. In California, Rice met Clarence White of The Byrds and absorbed his precision as a rhythm guitar player.

“A lot of people talk about Tony’s lead guitar playing, but he was a monster rhythm guitar player,” Vince Gill remarks.

In 1979 Rice formed his own group, The Tony Rice Unit, and over the next 40 years he played in a variety of combinations with musicians including Ricky Skaggs, Sam Bush, John Cowan, and Béla Fleck, among many others. He was voted the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Instrumentalist of the Year six times, and albums such as Church Street Blues and Manzanita continue to influence musicians across genres.

Here’s a closer look at the tribute albums that have emerged to celebrate Rice’s life and legacy.

Barry Waldrep’s Wide-Ranging ‘Celebration’

Seven years ago, multi-instrumentalist, singer, and producer Barry Waldrep recorded James Taylor’s “Me and My Guitar” as his contribution to a Tony Rice benefit album that never got made, and ended up shelving the song. But he pulled it back out after Rice died, and it became the seed for an entire tribute album.

“I grew up playing in a hardcore bluegrass band with my dad,” he says, “and Tony’s music was a huge influence.”

Waldrep, co-founder of the bluegrass/jam band Rollin’ in the Hay, which has released a slew of bluegrass tribute albums to artists including Eric Clapton, the Allman Brothers Band, Alan Jackson, and Lee Ann Womack over the years, knew just what to do. He called up a wide range of musicians, including Vince Gill, Spooner Oldham, Emmylou Harris, Kim Richey, Jim Lauderdale, Radney Foster, Rodney Crowell, Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams, and Wet Willie’s Jimmy Hall, whose styles represented a wide range of music. Barry Waldrep and Friends Celebrate Tony Rice, released on Christmas Eve, “puts together people who were influenced by Tony Rice but who have been doing other things,” Waldrep explains. “I started out thinking I’d do a 10-track CD, but by the time I got responses from everybody, it had become a 21-track CD.”

The songs Waldrep chose for the album represent a wide swath of Rice’s career, spanning “Why You Been Gone So Long,” “Church Street Blues,” “EMD,” “Cold on the Shoulder,” “Early Morning Rain,” and “More Pretty Girls Than One.” And though every musician on the album had widely different experiences with Rice’s music — and quite a few never had the chance to meet him — all of them expressed their deep admiration for his work.

After he heard Doc and Merle Watson in high school, Radney Foster, who sings “Songs on a Winter’s Night” on this collection, chucked all his electric guitars and dug deep into roots music.

“It didn’t dawn on me until much later how much influence Tony Rice’s music had on me,” he says. “When Tony Rice played a solo, he could bring melodic influences into it. Every time I’m thinking about how to make the melody and structure of a song, I’m thinking about how Tony Rice would do this.”

Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams deliver an aching version of “You Were There for Me” on the album. Campbell remarks that “Tony was one of the musicians expanding the genre while holding onto the essence of what made it great in the first place. There are names that will be written in the stars that illustrate the growth and expansion of American music. What an imagination and broad vocabulary; at the time it was just revolutionary.”

John Cowan met Tony Rice very early: “I think he was still playing with J.D.” Cowan, who plays with New Grass Revival and the Doobie Brothers, plays bass on most of the songs on Waldrep’s album, and sings lead on “Me and My Guitar.” He acknowledges Rice’s brilliance as a guitarist, but also emphasizes the clarity and purity of his vocals.

“He’s an amazing singer with a beautiful baritone; his singing is so important,” Cowan says. “I think there’s a Frank Sinatra quality in Rice’s vocals. Sinatra wrote the book on lyrical singing, and he could paint with his voice, and Tony’s vocals do the same.”

Jim Lauderdale, who like Cowan played with Rice, delivers a heartfelt take on Rice’s iconic “Church Street Blues” on the album. Lauderdale recalls Rice as “such a sweet guy; people just loved him so much. He was a down-to-earth, funny, and unpretentious guy.”

He also had “excellent taste in material,” Lauderdale points out. “He could go back and forth between experimental times when he was plowing new ground and then back to bluegrass; his playing was really dynamic.” Lauderdale also praises Rice’s voice as much as his guitar playing. “[It was a] pleasure to listen to him; he didn’t sound like anyone else and wasn’t trying to sound like any other bluegrass singer.”

Punch Brothers Make Room to Imagine

An album of Tony Rice songs hadn’t even crossed Punch Brothers’ minds in 2020 when they started discussing their next album. They just knew they wanted to get back into the studio again to write and record.

In November 2020, deep into the pandemic that had kept them off the road and apart from each other, the band finally gathered in a studio in Nashville.

Punch Brothers (photo by Josh Goleman)

“It’s the great joy of our lives to play music with each other,” says Punch Brothers guitarist Chris Eldridge. “We wanted to convene as Punch Brothers and make a record.” But what kind of record could they make, they wondered? “One of the things about our band is that we like to do a lot of writing together; the arranging is almost equally important as the writing. Punch Brothers doesn’t lend itself to chord charts,” Eldridge chuckles. Could the group engage for a slightly different project? What about an album of covers?

Banjo player Noam Pikelny reminded them of a set the band had put together for the 2019 RockyGrass Festival in Colorado in which they reimagined Rice’s Church Street Blues and suggested they work that set into a record of their own.

“All five of us love the record,” says mandolinist Chris Thile. “It’s foundational for all of us. There’s lots of textural acreage on the album; if you’re gonna go in as a band, there’s lots of room to imagine. Consider what would happen if Punch Brothers bounced itself off this record with all of our bodies, minds, and souls? These are all cover songs anyway, and we got to play a game of telephone with Tony Rice.”

On Hell on Church Street, released earlier this month, Punch Brothers deliver expansive versions of Rice’s Church Street Blues songs that honor the originals and move them to a different plane. The title track scampers along a gliding rhythm that builds on Rice’s original melodic solo. The blazing instrumental “Cattle in the Cane” features Pikelny and Eldridge trading note for note as the song spirals toward its climax. Rice always shined a light on Gordon Lightfoot’s songs, and Punch Brothers do the same with their ethereal version of the album’s final song, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

Rice was still alive when the band started work on Hell on Church Street, “and we hoped to share it with him,” says Thile. “He’s always been super generous to us over the years. We wanted to thank him for being one of the biggest influences on us and anyone who interacts with American music.”

When Rice died, the band was sad that they would never be able to give him their gift. But Pikelny reflects, “After we got over the shock of losing our hero and friend, we realized what Tony had left us with was his music, his spirit, and his legacy. And clear marching orders to ‘make it all count.’”

In addition to their musical admiration, some of the Punch Brothers members had personal experiences with Rice they’ve come to cherish.

“When I was 18 or 19, he took me under his wing,” Eldridge recalls. “He used to come sleep on a couch in our house when he was in DC. We almost never talked about guitar playing at all, though. He would tell me to be someone who loves music and someone who facilitates great music being played. It’s about collaborating with your fellow musicians.” According to Eldridge, Rice was “more interested in hearing the people behind the music; he cared so much about connecting to the humanity of the music.”

In his lifetime, and, evidently, even beyond, Rice used all his strengths as a composer, singer, guitarist, song finder, creator of taste to “make all the musicians around him play better,” Thile says. “He would look around to see what he could make better.”

Dan Tyminski Continues a Musical Conversation

Dan Tyminski, singer, guitarist, and longtime member of Alison Krauss & Union Station, also has a Tony Rice tribute coming this year, though the five-song EP, titled One More Time Before You Go, wasn’t something he’d planned.

“I was in pain over losing my hero,” Tyminski recalls of the time after Rice’s death. “In the process of healing myself, I had an idea for one song. I had a melody that I’d been playing even before Tony died.”

Dan Tyminski (photo by Scott Simontacchi)

Tyminski called up Josh Williams, who played with Rice in his last years, and the two sat down and wrote the song, “One More Time Before You Go,” a loving homage to Rice and his musical legacy. In the song’s refrain, Tyminski sings directly to his friend: “Of all the precious memories that I hold / The ones that mean the most are all the stories you told / If I could just go back and trace your footprints in the snow / I’d have you tell them all just one more time before you go.”

Tyminski wondered what the song would sound like with a full band, so he invited Jerry Douglas, Sam Bush, and Todd Phillips to make the version that is on the EP. The rest of the songs on the album are Tony Rice songs, and Tyminski invited some other musicians to duet with him on those, including Molly Tuttle on “Church Street Blues” and Billy Strings on “Where the Soul of Man Never Dies.”

Like so many other musicians, Tyminski clearly recalls the first time he heard Tony Rice. It was on J.D. Crowe and The New South’s eponymous first album, known to many by its label and number, Rounder 0044. “When I was 13, I was listening to the 0044 record, because I thought I wanted to listen to J.D. Crowe since I thought I wanted to be a banjo player.” Eventually, however, he found his ear drawn not to the banjo lines but to the rhythm guitar player: “I listened to a couple of songs over and over again.”

According to Tyminski, Rice breathed life into the music he played, and he affected the music world so deeply because of the way he influenced other people’s playing. “When he played, he made people play things they didn’t think they were going to play,” says Tyminski. “Tony responded to what he heard, and when he responded, he would get you to answer back, and then he would respond and you would answer. He started a musical conversation.”

These three albums continue Rice’s legacy by doing what he sought to do in his own music: They capture the soulful spirit of the music and innovate in ways that honor the depth of the original songs.