‘Truly Handmade’ Collects Guy Clark Demos From His Storied Workshop

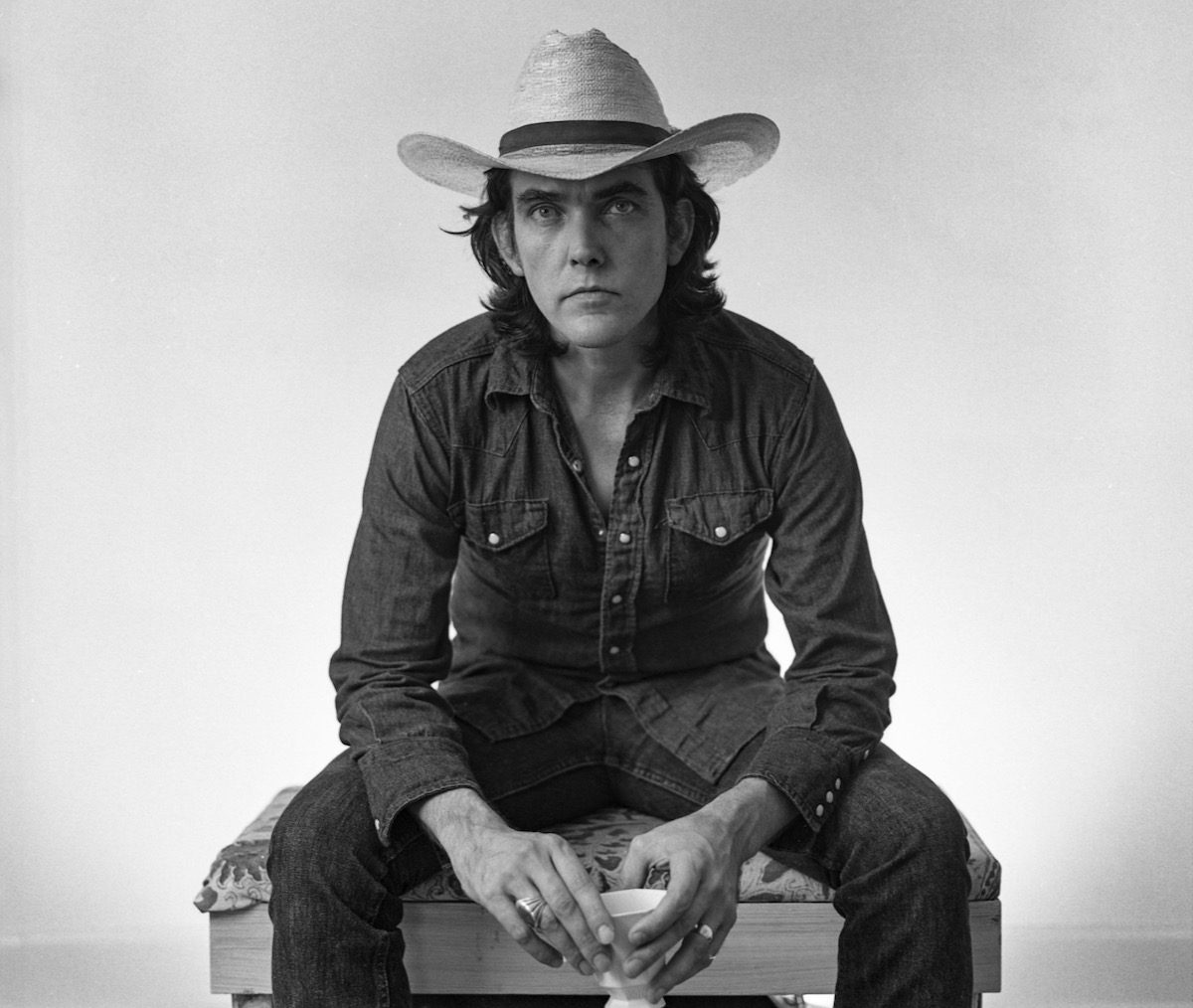

An undated image of Guy Clark released in conjunction with the documentary "Without Getting Killed Or Caught." (Photo by Marshall Falwell)

One of the many highlights at The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville is a painstakingly accurate recreation of Guy Clark’s workshop, the basement haven where he would go to work on guitars, solve life’s problems, write songs and sometimes demo them. It was a key part of Clark’s creative process and his Nashville home, which was a place for his musician friends to visit and swap stories and ideas while sharing his love of creativity and the craft of a song.

Collected on the right wall of the workshop exhibit are rows and rows of replicas of Clark’s cassette tapes. The originals contain rough demos of songs he had worked on to varying degrees throughout his long career. Clark passed in 2016, and he was followed 18 months later by his only son, Travis. A couple of years later, Clark’s grandson, Dylan, realized it made no sense for these tapes to just sit on a wall collecting dust. He believed Clark’s many fans deserved to hear what those cassettes contained.

Dylan, who is not in the music business himself, knew they needed to be transferred to digital, but that it would be a daunting task. “As soon as I laid eyes on the tapes, I knew I was out of my depth,” he admits. “And transfers needed to be done by a professional. It wouldn’t have been right to let them waste away, and now the songs can be enjoyed.”

Ultimately, hundreds of Clark’s homemade demos were transferred from tape to digital. That’s when the treasure hunt began. Clark’s longtime friend and sometime songwriting partner and producer Rodney Crowell acted as producer and curator for the resulting collection, called Truly Handmade, Vol. 1 and released May 3.

A replica of Guy Clark’s workshop in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville. His collection of tapes is visible on the right wall. (Photo by Elizabeth Elliott)

Guy Clark, Unadorned

Tamara Saviano, author, Grammy winner, producer, and Clark’s biographer and documentarian, was the first to get the files after they were digitized. “I just sent everything over to Rodney [Crowell] and I said, ‘You produce it. You do whatever you think is right, and we’ll put it out,’” she says.

“I knew all the tapes. Well, a lot of them,” Crowell explains. “I was around when the demos were made back in the ’70s, but I wasn’t sure what I was looking for. I just had to go through everything and see where we should start.”

Figuring the best place was at the beginning, Crowell found his ground zero with the guitar and vocal demos for “L.A. Freeway” and “Old Time Feeling,” cut before Clark’s classic 1975 debut, Old No. 1. Hearing those early raw performances placed him right back to where it all began. “It meant a lot to me because it was around the beginning of my friendship with Guy,” Crowell recalls. “He invited me in and played the songs for me and it’s just the way I remember them. Just him in the kitchen.”

Crowell focused this first volume on the years spanning Clark’s very early days through demos that ended up on the Crowell-produced 1981 album The South Coast of Texas. He whittled a mountain of material down to 15 tracks of just Clark and his guitar, with songs both well-known to Clark’s fans and some that have rarely, if ever, been heard. According to Crowell, there was no doctoring of any kind. The tape hiss is still there. What you hear is just exactly what Clark recorded.

“I thought any Guy Clark fan would be really satisfied to get him that way,” Crowell says, as well as anyone discovering him fresh. “I mean, it’s unadorned, and beautiful. And beautifully him.”

The Elegance of Guy

As he was present when many of these demos were recorded, Crowell was a clear choice to produce Truly Handmade, Vol. 1.

“We weren’t making records yet,” he recalls of the era in which these recordings were made. “It wasn’t a job. It was an event and a demo session. I’d get phone calls that said, ‘Hey man, I got a demo session. Come on up.’ It was moral support, but it was also an excuse to have a party at somebody else’s expense. We were like, ‘Hey, Guy’s putting down a new song. Come on. We’ll get drunk!’”

The friends on the other end of those phone calls were a who’s-who of the 1970s progressive country scene. Young songwriters hustling to make their way in Nashville — Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, Steve Runkle, David Olney, and others — were regulars in Guy and Susanna Clark’s kitchen. “We hadn’t yet been let into a studio,” Crowell explains. “But Guy was so generous. He would show you the songs. He took pity on me or saw something in me. Truthfully, it’s the fact that I’d learned so many Appalachian dead baby songs from my dad, that I was a source of entertainment at 3 a.m. when everybody was drunk and out of songs. So, for me to curate these songs was to be one more time back in those rooms or on Acklen Avenue when I was running with Skinny Dennis and Richard Dobson and those all-night song swaps. I got to be there again for a minute. But whether you were there or not, you can hear the elegance of Guy and just the way he sang and played the guitar.”

“It’s the one I regret, because I didn’t have the vision at the time to realize that I needed Guy to sit down with his guitar and play these songs and then have musicians fill in around him,” Crowell says. “The thing of it is, Guy was so pissed off. Pissed off at me but also pissed off at the system because the system was trying to make a hit record with Guy when what needed to happen was that Guy just needed to be himself. He was going to have his audience base and they were going to love him, and he was going to have a long career. And he figured that out on that record.”

Sure enough, with his next album, 1988’s Old Friends, Clark transitioned to the small but scrappy Sugar Hill label, a home more concerned with an artist’s legacy than with chart position. The string of albums that followed cemented Clark’s status as a father of the then-fledgling Americana format.

But on Truly Handmade, Vol. 1, Clark is still a fledgling himself, searching, yet already somehow a fully formed songwriter of surprising economy and depth.

In addition to “LA Freeway,” “Old Time Feeling, “Nickel for the Fiddler,” and “Let Him Roll” – all from Old No. 1 — there are stripped-down versions of “Who Do You Think You Are,” “Calf Rope,” and “Lone Star Hotel Café,” songs that eventually appeared on The South Coast of Texas. Longtime fans will also get to hear Clark’s demo of “Don’t Let the Sunshine Fool You,” a song Townes Van Zandt recorded on 1972’s The Late Great Townes Van Zandt. Clark’s version sounds more celebratory, immediate. Then there’s “All the Way From California,” which acts as a possible sequel to “LA Freeway,” where the narrator is neither killed nor caught. Instead, he’s back home in Texas, but realizing the grass may be greener back in the Golden State.

“Hold On Brother” emphasizes Clark’s optimism; one can imagine him singing its lines to one of the many struggling songwriters around his kitchen table or down in his workshop. “Miss Alice Pringle,” never before released, reveals another side to Clark, as its melody and performance wouldn’t sound out of place on an early ’70s Paul Simon album.

“I had first heard Guy and Susanna sing it to me in the kitchen,” Crowell recalls of the song, “and I would always wheedle Guy about recording it. And lo and behold, the version that I uncovered is just the way I remember hearing it in the kitchen.”

Inside the House

A clear highlight of Truly Handmade, Vol. 1 is Clark’s version of “Step Inside My House,” one of the first songs he acknowledges writing. Lyle Lovett covered it, as “Step Inside This House,” and made it the title track on his 1998 double-album tribute to Texas songwriters. For Dylan Clark, hearing it sung by his grandfather was “a standout and surprise,” reminding him of “the family sitting around the dining room table on holidays eating takeout from [Nashville restaurant] Dalt’s and just talking about life.”

Dylan’s experience going through the tapes brought back many of those memories, and it also allowed him to become more familiar with his grandfather’s peerless catalog. “I’m pretty familiar with the later albums,” he says, “Like Cold Dog Soup and everything after, but most of the reels were unlabeled or no longer legible, so I had no idea what was on them.”

With those reels digitized and in possession of Saviano and Crowell, there’s a lot in the vault for fans to look forward to in the future. “I actually just got another set of reels that needs to be digitized from someone,” Saviano says. “So, things just keep turning up.”

In fact, there are, according to Saviano, “hundreds and hundreds” of songs to sift through. “This was just the beginning,” Crowell assures. “There are some lost tapes that we need to find.”

There’s one in particular he’s on the lookout for: “It captures an irredeemable night with Don Everly and me and Bee Spears and Guy and Waylon all just in a studio with the tape rolling. I hope we can find it.”

In the meantime, Dylan’s favorite Guy Clark song seems to describe his grandfather’s legacy to a T. “My personal favorite is ‘The Cape,’” he says. “A lot of his songs were so serious, but that one is deep and farcical at the same time, much like he was with us.”