Up There in the Wind, Listen for Johnny Cash — His Voice, Memory and Vision

Once, hunters and their tribes and families roamed and thrived through the plains and deep woods of America. Then the white man came, and eventually, after many bloody physical and political battles, came what Johnny Cash called “bitter tears.”

I gained a graphic sense of this in 2013 when I saw — at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend — the stunning and heroic work of the great photographer Edward S. Curtis. He documented the demise of America’s native culture from a governmental genocide that led to a tribe reservation system largely segregated from American society. The powerfully transporting exhibit revealed indigenous peoples all across America still hanging on to their natural habitat and way of life, before it was destroyed and partitioned out by the white man. At the top of this article is a portrait Curtis took of a warrior named Bear’s Belly, or Arikara, wearing a bearskin that served perhaps as camouflage in battle with cowboys and solidiers. Then, in 1908 he re-enacted the Ceremony of the Bear Medicine Fraternity, for Curtis’s camera.

The Curtis photo exhibit prompted me to read Timothy Egan’s fascinating biography of Curtis, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher. His life story provided great insights into Curtis’s accomplishment and what our Native Americans endured, lost — and sustained as a society and culture — despite all odds. (1)

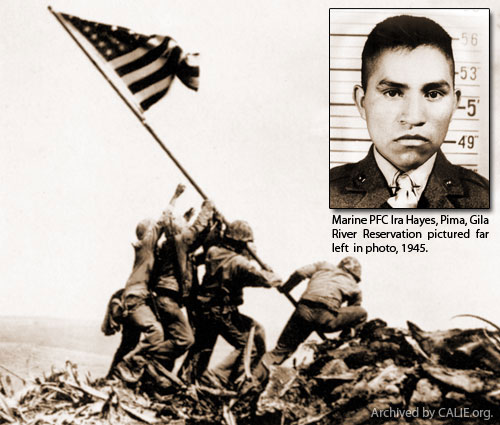

In 2014, I read Robert Hilburn’s powerful and probing biography Johnny Cash: The Life. It told of how Johnny Cash became the first major popular music artist of the era to address the ongoing plight of Native Americans, in his pioneering 1964 concept album, Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. That album was partly inspired by Cash meeting songwriter Peter LaFarge, a man with mixed Native American blood, who was writing “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” and other compelling songs. Hayes was the Native American who was among the Marines who hoisted the iconic American flag at Iwo Jima in World War II. Then, after a celebratory return home, Hayes died in tragic circumstances.

Native American Marine Ira Hayes is on the far left in Joe Rosenthal’s famous photograph of the raising of the American flag at Iwo Jima, near the end of World War II. Courtesy californiaindianeducation.org

The album’s cutting edge emerged almost immediately in the lack of promotion from Columbia Records, whom Cash termed “gutless.” In his biography, Robert Hilburn captures Cash’s own bitterness: “They found a lot of resentment from country DJs over the subject matter; they feared their conservative listeners would tune out, so they buried the record, and Columbia just rolled over.” (2)

In a way, Cash was my generation’s Edward S. Curtis, telling the truth in songs with their own images.

Since his death in 2003, many roots musicians have celebrated Johnny Cash’s vision and artistic power notably in the live album and DVD We Walk the Line: A Celebration of the Music of Johnny Cash. It’s a high-spirited, poignant, sometimes magical live concert evocation of the man’s legacy, which was my choice for No. 2 roots music album of the year in 2012, both on my blog and on NoDepression.com. (3)

Then last summer, 50 years after the original release, came the deeply moving tribute album, Look Again to the Wind: Johnny Cash’s Bitter Tears Revisited, on Sony Masterworks. That label has belatedly redeemed the reticence Columbia Records displayed when the original album essentially disappeared at its birth, like a small Indian burial mound, standing alone and windswept in a remote prairie.

Johnny Cash (upper) touring the site of the 1890 massacre of Native Americans at Wounded Knee with survivors, in December of 1969. And Cash (lower) near the time that he recorded “Bitter Tears.” Courtesy (respectively) of salon.com and latimes.com

As it happened, this year I experienced — especially in an October road trip to San Francisco and the world-class SF Jazz Center — a focus on the pan-cultural vitality of America’s original art form: jazz. I didn’t write about Look to the Wind, in any detail. But, I heard its solemn power and stirring pertinence, and chose it as my number seven roots music album of the year, without comment. So I’m grateful that my former colleague at The Capital Times, John Nichols, and The Nation’s Washington correspondent, assessed the album as succinctly as anyone could in his recent “2014 Progressive Honor Roll” in the January 12/19 issue of The Nation. Here’s what Nichols wrote:

Most Valuable CD: Look Again to the Wind: Johnny Cash’s Bitter Tears Revisited

There’s an argument to be made that Johnny Cash sang the most adventurous protest songs of the 1960s. Exhibit A: his 1964 concept album Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. Cash was a top-of-the-charts singer, but radio wouldn’t play it. So he bought a full-page ad in Billboard, decrying a “gutless” music industry for refusing to consider the plight of Native Americans and linking it to broader questions raised by civil-rights campaigners and a then very small antiwar movement. Yes, he declared, his songs were “strong medicine…. So is Rochester, Harlem, Birmingham and Vietnam.” That strong medicine would influence a new generation of singers who jumped at the chance to reintroduce Cash’s Bitter Tears to America. Steve Earle captures the spirit of the project’s demand for a rethinking of history when he sings, “I will tell you, buster, that I ain’t a fan of Custer….” Bill Miller, who heard the original album as a kid growing up on the Stockbridge-Munsee-Mohican reservation in Wisconsin, offers a brilliant take on the project’s title track (written by the late Peter La Farge). And Kris Kristofferson, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings capture the passion of one of the greatest protest songs ever written, “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.” Fine music. Fine politics.

Native American flutist Bill Miller, Courtesy billmiller.com

Miller, a guitarist and master of the Native American flute, underscores Nichols praise: “It has a deeper respect for Native Americans than any other project I’ve been involved in,” he says in the album’s promotional video.

Sony contacted Miller and he left his mother’s deathbed in Shawano, Wisconsin to do this project. “We are people with gifts and blessings and we can still bless this world, something that history and Hollywood has overlooked,” he says.

A tour of artists involved in recording the album is in the works, Miller says. “It’s meant to happen,” he says.

Singer-songwriter-author Steve Earle and singer-songwriter Gillian Welch are among an all-star group of musicians who reinterpret Johnny Cash’s 1964 “Bitter Tears” album as “Look Again to the Wind.” The lineup also includes Mohican flutist Bill Miller, Emmylou Harris, Kris Kristofferson, Norman Blake, and Carolina Chocolate Drops’ lead singer Rhiannon Giddens and others.

Lead photo: Arikara (Bear’s Belly), By Edward Curtis, 1908. Courtesy The Museum of Wisconsin Art

1 Edward S. Curtis preserved America’s Vanishing Race for Posterity, art exhibit review.

2 Johnny Cash: The Life, by Robert Hilburn, Little, Brown and Company, 2013, 265. See book review.

3. We Walk the Line: A Celebration of the Music of Johnny Cash, album/DVD review.

4. Here is John Nichols’ complete article on his “2014 progressive honor roll.”