Web Metrics & the Meaning of Lifetime: The Case of Gram Parsons

In these days of Linda Chorneys and Lana Del Rays, it’s getting increasingly difficult to deal with the criteria used to nominate someone, and in which category even, whether for halls of fame or for the likes of the Grammy Awards. There are clearly ways to “play the system” if indeed there still exists a system to be played. You have to know your way around the Casino.

And when it comes to “lifetime achievement awards,” which would also include induction into halls of fame, the definition of “lifetime,” which had become “15 minutes of fame,” seems now to be reduced to about a nanosecond.

Add the landscape-altering shifts in “categories” and their qualifying criteria, such as airplay (“spins” adding terrestrial and satellite), and unit sales (now including 0’s and 1’s, electrons either embedded in plastic discs or just free flowing), streaming, pirated, etc., and you are left with a real tossed salad, especially when dealing with artists whose careers have spanned these relatively recent revolutions, or even those who lived when music had only two vehicles — live or Long Playing (LPs).

Trends in measuring popularity, success, artistic accomplishment, and any other yardsticks involved in nominating an artist for any such “lifetime” accolades become increasingly complex when dealing with those whose careers either spanned these changes that have rocked the business, or who lived their lives entirely in a statistically simpler, more easily quantifiable time.

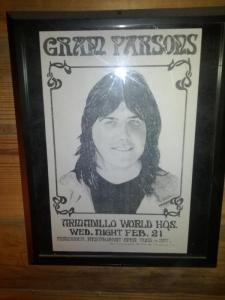

As an example, let’s examine an artist on Rolling Stone’s List of 100 Greatest Artists of All Time, who has been nominated to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame three times, has been the subject of a slew of biographies in both books and film, and who is the subject of a global petition to induct him into the Country Music Hall of Fame with over 11,000 signers so far. He is arguably eligible for a lifetime achievement award or hall of fame induction, even though that lifetime lasted just under 27 years. In this case, another question might be added: Should the criteria for lifetime achievement be expanded to factor in that artist’s influence and popularity if exponentially expanding posthumously?

The article, which mainly outlined the then-little-known facts concerning this obscure artist and hinted at his historical importance, would be silly if published today. The idea that these basic facts would be flushed out over the following decades in microscopic detail by so many biographies, movies, plays, etc., was inconceivable at the time of that fifth year benchmark. All his records were out of print, and there was no Internet or alternative channels of distribution.

Fast forward back to the present; strange days have indeed found us. Clearly a variety of metrics is needed to even guesstimate an artist’s place in history over the years. Indeed, in some ways we live in an era when popular icons seem to never really “die” (e.g., Princess Diana).

It’s well known that Gram Parsons, for a variety of reasons and missed opportunities, sold relatively few units while alive. It’s believed that the only royalty check he ever received was due to Joan Baez recording “Hickory Wind.” His records were out of print shortly after his death. Lacking any other means of distribution, there was about a 20-year period during which the only way to find Gram was to scour used record stores and get lucky. But slowly at first, a fascinating and somewhat unique phenomenon occurred. While vinyl sales were relegated to the occasional bootleg collection of unreleased Flying Burrito Brothers material, the popularity of this by now almost mythical figure in American music began to soar, at first by the age-old “oral tradition,” that is, by other musicians, those who have always led Gram’s resurgence, covering his songs and preaching his significance, followed by fans of these latter day singers spreading the word.

Today, web metrics can be helpful in measuring the comparative interest, value, importance and significance of a search term and thereby the subject in question. The key word in the last sentence is comparative, either to itself over a specified time period or in comparison to other terms that share characteristics in common. The following observations, which is all they claim to be, are mainly of the latter type; looking at search engine result pages (SERPs) for artists in similar genres to Gram Parsons, and those who may already be elected to a hall of fame or who have been associated with Parsons in a famous band and have gone on to a full lifetime of many and various achievements. (Results for any not included here can be found in seconds by the reader.) While these metrics do not necessarily correlate with unit sales, an argument can be made that the greater the number of search engine results returned, the greater the conversion of these user-generated inquiries into an action associated with acquiring the artist’s product (hopefully a purchase). The results of such an analysis obviously don’t point to a conclusion by themselves; however, they may add a quantifiable factor to such an analysis of lifetime achievement.

For example, using Google and searching for “Gram Parsons” in quotes (to be sure we don’t get returns for an international unit of measurement!), Google returns 2,160,000 results (note: depending on Google’s algorithms, which change often, these numbers will change; those given here were taken within an hour of the same day). Again, not much you can do with that number except a basic comparative analysis. For example, Parsons’ total of SERPs is exactly one million more than for the words: Roger McGuinn, Gram’s boss with the Byrds and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee (who returns 1,160,000). Fellow Byrd and Flying Burritio Brother bandmate Chris Hillman returns 506,000. In fact, the only Byrd to out-return Parsons is David Crosby, no doubt less for his antics with the Byrds and more for his subsequent fame with CSN&Y.

While the Country Music Association insists “Quantity” is not a vital consideration in determining Hall inductees (see this article), it’s common knowledge that it’s weighted greater than the criteria state. Again for what it’s worth, a comparison of Parsons 2+million search engine returns reveals the following in comparison with some random recent Country Music Hall of Fame inductees:

Interestingly, a great songwriter with certain similarities to Gram, Townes Van Zandt comes in at a statistical dead-heat at 2,190,000.

Parsons’ protege and reigning queen of both country and “Americana” music, Emmylou Harris, returns a whopping (and not surprising) 6,300,000, approximately three times as many as her mentor, whom she often credits for her knowledge of country music. Had Gram lived one could easily assume a roughly equal number as his career was roughly one third as long (and one could also envision a huge number for the two of them together as probably the biggest country duo act in history).

Obviously this has been a cursory analysis only meant to point out that Internet SERPs and related metrics can find a place in, and assist in informing, historical market trend analysis, and may help us notice that which otherwise may remain obscure. More refined metrics analyses would and could obviously produce more target-specific trending, and/or historical, data.

So as we move forward to analyze the train wrecks that are the award shows, and more specifically their categories and nomination procedures, those involved may want to get up to speed on this paradigm, one that is quantifiable while also being more widely relevant to the industry’s current consumer base. Doing so may assist in making the more subjective judgments at the heart of making such calls.

And as in the case of Gram Parsons, such an empirical analysis may also show that one’s career may not only not end with his or her life but indeed may show that such a career requires re-definition to include the full scope of activity, including purchases, for that artist, whether still with us or not. (After all, to risk a “John Lennon oops! moment,” I believe it took Jesus a few hundred years to really get noticed!)

Originally published Feb 15, 2012 in http://gramparsonsinternational.us.