50 Years After Woodstock, The Music Plays On

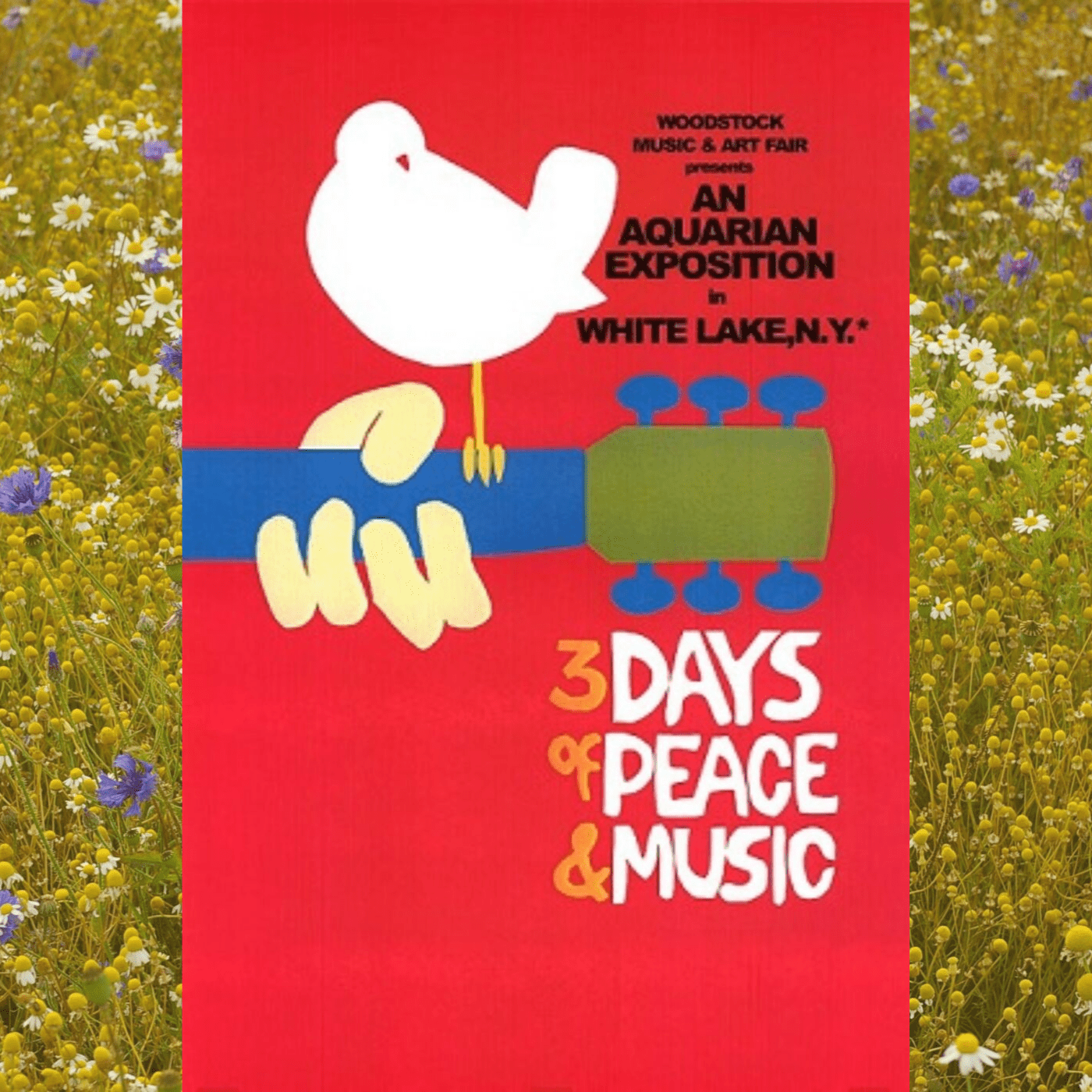

Woodstock poster by Arnold Skolnick (who has said he was paid $15 for the design of the white dove on the neck of a guitar, against a red background).

Fifty years ago today, a little past five in the afternoon, on a stage planned and lit by E.H. Beresford “Chip” Monck, who introduced him, Richie Havens found himself the surprise opening act of “An Aquarian Exposition” presented by the Woodstock Music & Art Fair. Resplendent in an orange caftan and accompanied by Daniel Natoga Ben Zebulon and Paul “Deano” Williams, Havens led off with the haunting, gentle “From the Prison” and concluded with “Freedom.”

The details of what history calls the Woodstock festival have been copiously and compulsively chronicled since it happened: who played there and who didn’t; who attended, who claimed to, and who didn’t; what its importance was in the history of American music, America, and music worldwide. You can read plenty of pieces about the musicians who came and what their set lists were in all the Woodstock 50 essays appearing this week, and I encourage you to. What I’ve been thinking about, though, is the effect that a concert held nearly 60 miles away, in the end, had on a little mountain town at the foot of the Catskills.

Brooklyn-born but Woodstock-based Michael Lang, in partnership with former Capitol Records VP Artie Kornfeld, had planned that the concert be near Woodstock when they named their promotion company “Woodstock Ventures” in early 1969. Sound recording entrepreneurs Joel Rosenman and John P. Roberts (whose mother’s family, the Blocks, had founded the drug company that made Polident, Nytol, and Sensodyne) joined them, and together the four men contemplated a location first in Walkill, New York (townsfolk banned the concert in mid-July in a panic over how many people might come), and then between Woodstock and Saugerties. By late July, the residents of Bethel, New York, near Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm where “Woodstock” was meant to happen, were trying to stop the festival too. They failed, and Woodstock, the town, supplied only a name — avoiding vast amounts of traffic (foot and car) and the mudification of everything, and gaining an eternal if wrongful fame among music fans.

The fact is, though, Woodstock didn’t need the fame. The little Ulster County hamlet, founded in 1787 — as the 13 states existing then were drawing up a Constitution for their new country — was itself sited on an old Lenape village. The Native tribes of the area left their names in the land, even as they were pushed off it by settlement and war: Esopus Creek and Ohayo Mountain are on the map alongside the Dutch (Saw Kill; Hasbrouck) and English.

Just over 10 miles from the Hudson River, and a hundred from the Upper West Side of New York City, Woodstock quickly changed from a farm town into a place for tourists seeking health in the salubrious mountain air during spring and summer. In 1833, the first of a series of hotels was built on the highest wide shoulder of Overlook Mountain.

With the tourists came more permanent residents, artists drawn up the Hudson who gave their name to the “Hudson River School” of painting by the middle 1800s. Chief among those was Thomas Cole, an intense-eyed, black-haired young man from Lancashire whose family had emigrated to America when he was 17. With a philanthropist’s backing, Cole made a trip to paint Hudson River scenes. His intensely Romantic depictions of the Catskills, Cold Spring, riverbends, and foaming waterfalls made visual for all America the same scenes Washington Irving was sketching in stories like “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820). Cole eventually settled in Catskill, welcoming younger painters, including Frederic Church, to study with him.

A few decades later, another English-born immigrant, Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead, arrived in the area with his wife, Jane Byrd McCall, and used his family inheritance to try to put into practice what the critic John Ruskin and artist William Morris had taught him about the possibility of an artistic utopian colony. They finally succeeded in 1902-03 on a thousand and a half acres spread between Woodstock’s twin sentinel mountains, Overlook and Guardian. “Byrdcliffe,” a combination of the couple’s names, became and remains an arts community with an artist-in-residence program that welcomes painters, composers, poets, ceramicists, weavers, and more. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald visited friends at Byrdcliffe in the summer of 1927; Bob Dylan and his family lived in Hi Lo Ha, one of the Arts and Crafts houses original to the colony, in the late 1960s.

Woodstock’s association with music did not begin when Dylan bought a house there in 1965. His manager, Albert Grossman, was the one who’d invited him there. Grossman and his wife, Sally, had owned a home and substantial property two miles west along the creek flats from Woodstock, in Bearsville. Daniel Kramer came up from the city to photograph Bob and Sally for the cover of Bringing It All Back Home in early 1965. The more recent owners of the Grossmans’ house, writer Neil Gaiman and musician Amanda Palmer, kept the sofa.

However, Woodstock’s music history goes back well before all this: Byrdcliffe co-founder Hervey White turned his hundred-acre farm just outside town, known as “the Maverick” (and White most assuredly was one), into a music and theater festival site in 1915.

The photographs of his “Maverick Festivals” in the Woodstock Historical Society show us that costumes were outrageous or lacking, reams of jewelry and scarves and flowers in the hair were required, and the numbers grew every year until the Great Depression and alarmed townsfolk stopped the show in 1931. However, White’s separately organized classical music concerts, in a rustic festival hall featuring wood-framed “Woodstock windows” with the patterns of cathedral glass and a regal horse carved from a single chestnut tree trunk in the corner, have continued from 1916 to the present. Paul Robeson sang in the Maverick Concert Hall, and John Tudor first performed John Cage’s 4’33” here in the summer of 1952. This summer’s scheduled events conclude in September with a free concert by Pedja Mužijević in memory of Alan Siegel.

Woodstock, the town, has never limited its musical world to folk, classical, rock, pop, or any other genre. Woodstock, the music festival, tapped into all that, thanks, I believe, to Michael Lang and his familiarity with the town and its history. Just think of the sweep, the variety, encompassed by the performers who played the festival: from the passionate rhythmic guitar strumming of Havens to the traditional clarity of Joan Baez; from the wild novelty of Leslie West and Mountain (in their third gig ever) to the funk of Sly and the Family Stone; from the ’50s redux of Sha Na Na to the blistering licks of Jimi Hendrix and Gypsy Sun and Rainbows. Roger Daltrey, curls streaming, and Keith Moon pounding the drums, driving The Who through a massive 24-song set that the band members all hated, though the audience loved it, at dawn. The Grateful Dead and their particular, lyric Americana of days long gone by, washed in psychedelia and jazz and made new again, balanced so beautifully by their musical soulmates in The Band.

The Band, more than any of the other performers in August 1969, define both Woodstock (the festival) and Woodstock (the town) in cultural consciousness today. Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, and Robbie Robertson had only recently started performing under the name “The Band,” though they had been playing together, with Ronnie Hawkins, since 1961 and together on their own (as The Hawks and The Canadian Squires) since 1963. Having backed Bob Dylan on his 1965 and 1966 tours, The Band’s members settled in and near Woodstock thereafter, with Danko, Hudson, and Manuel renting a pink house with a capacious unfinished basement in Saugerties. Robertson and his wife lived nearby, and Helm soon returned to the area from Arkansas. Their album Music from Big Pink (1968), which they recorded largely in the Saugerties house, catapulted them to fame, and the eponymous album released in autumn after the festival carved that fame in stone. Danko, Manuel, Hudson, and Helm chose to make the Woodstock area their permanent home, and continued to perform together until Manuel’s suicide in 1986. Danko and Helm are now buried in the cemetery in the heart of town. Hudson lives between Woodstock and Canada; he is now 82, and the sight of him with his thick white beard and perpetual black hat making his way across the little parking lot outside Sunflower Natural Foods arrests the attention of visitors, locals, and Woodstock’s many resident musicians alike.

The first time I heard Hudson play was, appropriately, at Helm’s. Levon began hosting the “Midnight Rambles” at his home on Plochmann Lane in 2004, and the very first show — with legendary piano man Johnnie Johnson as the special guest — was like a pebble in a lake. The ripples spread. People came to Woodstock to play with Helm, and stayed. Larry Campbell quit touring with Bob Dylan in January 2005, and Helm telephoned him soon after. “Let’s make some music,” Helm said, and soon Campbell and his wife, singer and guitarist Teresa Williams, had made their home in town. Campbell was the Midnight Ramble Band leader for six and a half golden years — and three Grammys.

Lineage of the “Woodstock generation” runs deep in town in personal as well as musical terms. Saxophone player Jay Collins married singer-songwriter Amy Helm, daughter of Levon and native-born Woodstocker and singer-songwriter Libby Titus. Collins and Helm are separated, but both remain in the Woodstock area; their son Lee had a small drum from babyhood and now, pushing teenage, is laying down beats that would make his grandfather mighty proud.

John Sebastian was swept onstage from the audience to perform at the festival in 1969, although he hadn’t been on the program. The Lovin’ Spoonful frontman would soon give up his homes in New York and L.A. for the Catskills, moving permanently to Woodstock with his wife, Catherine, and their sons. One of the sons, Ben, still based in town, is a singer-songwriter, percussionist, and artist who performs and records as Ben Vita. Rachel Marco-Havens, Richie’s daughter, is a local environmental and community advocate.

Certainly the Woodstock festival is being celebrated in and around town this weekend. Woodstock is already packed with visitors and traffic, and there is a spectacular exhibition of Elliott Landy’s famous festival photographs at the Center for Photography at Woodstock. Landy has lived in town for many decades; you can often find him at Bread Alone, where his art graces the walls.

Michael Lang, looking remarkably unchanged after 50 years, his mop of hair springy and genial face only lightly lined, will likely be at home, too. The Woodstock 50 festival he sought to organize in Watkins Glen, New York, after other successful anniversary shows, is not happening. On the original location of Yasgur’s farm, now Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, Ringo Starr and his All-Starr Band, The Doobie Brothers, Tedeschi Trucks Band, and Grace Potter will be joining original festival performers Carlos Santana and John Fogerty.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=AqZceAQSJvc

There is music aplenty, every night, in the many local Woodstock venues. The musicians range in age from their 20s to their 80s — Ed Sanders, frontman of The Fugs, will lead his band in a concert at the Byrdcliffe Theater, built as part of the colony in 1904, on Saturday, his 80th birthday. Simi Stone is at The Colony the same night. Robert Burke Warren will lead a sing-along of songs performed at the festival at the Phoenicia Diner on Sunday. However, the most palpable celebration of “Woodstock” in Woodstock is the way in which truly sensational young musicians are celebrating, and revitalizing, the area’s musical legacy while making powerful ways of their own.

Foremost among these people is Connor Kennedy. Kennedy was born a Jersey boy, but moved to Saugerties when he was five. At 10 he had his first guitar; at 14 he was helping to park cars for Midnight Rambles in the dirt parking lot by the lake at Levon’s. Kennedy first heard Helm play on a cold January night in 2009, when Helm’s old friend Hubert Sumlin was the special guest.

“That’s who I really wanted to go and see, because I knew Hubert was an influence on Jimi Hendrix, ” Kennedy recalls. “It was a snowy night, which impacted the turnout. I think there were about 20 or 30 people that night. A tree fell in the driveway, and we couldn’t leave until it had been moved.”

The Catskill winter weather that night meant that Kennedy was snowed in with Jimmy Vivino, Sumlin, and Helm playing “Milk Cow Blues.” Soon Kennedy was playing every Pink Floyd tune you could ask for, and honing his skills at outdoor farmers markets and larger indoor venues alike. One night when he was accompanying acclaimed singer-composer Lindsey Webster, born and raised in Woodstock, at the Bearsville Theater, Donald Fagen came to hear Kennedy. Came down, I should say, since Fagen and Libby Titus, married since 1993, live up the mountain from Bearsville in Byrdcliffe — in Bob Dylan’s old house. Fagen was about to play the Beacon Theater in New York with The Dukes of September, and Kennedy said he’d love to come to the show. “He said, ‘why don’t you come and play with us?'” Kennedy accepted swiftly. He was 17. In 2017, Kennedy and his own longtime bandmates Lee Falco (drums), Brandon Morrison (bass), and Will Bryant (keyboards) joined Fagen on an American tour as the Nightflyers. Kennedy was invited to join Steely Dan in early 2019, and is about to leave for two months on the road in the band’s upcoming Sweet tour. Age is just a number for Woodstock artists. The 25-year-old Kennedy says, with a grin: “Donald’s the youngest person in Steely Dan.”

The town of Woodstock is all about connections and continuities, influences and intersections, and — in Levon Helm’s phrase, the desire and ability to “keep it goin’.” Helm thus urged his family and bandmates to continue the Rambles during his last illness, and blessed the idea his close friend Phil Lesh had to begin a “western Ramble” in San Rafael, California. Lesh, whose son Grahame is now making music with Amy Helm, will come to honor Levon at the Dirt Farmer Festival down the road in Accord on Sept. 6. This area, so fertile for centuries of creative people, still draws them here, not just to commemorate a single summer event, but to cherish and continue the spirit and culture that led the “Aquarian Exposition” to be engendered here in the first place.